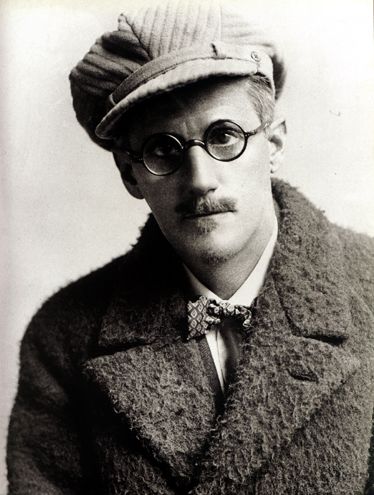

JAMES JOYCE

James Joyce was one of the most celebrated and influential English-language writers of the 20th century, and his later works of fiction, Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939), are generally regarded among the most challenging (and, for many, rewarding) works of literature produced in any language. All of his fictional writing drew somehow upon the circumstances of his own life, and, despite a self-imposed exile that lasted most of his adult life, his fiction always took place in the city of his birth, Dublin. In fact, Joyce has rendered Dublin so powerfully on his pages that generations of readers have been drawn to the city to experience a place they have already, in a sense, come to know.

Joyce was born in the south Dublin suburb of Rathgar, on February 2, 1882, the eldest of ten children born to John Stanislaus Joyce and Mary Jane (Murray) Joyce. At the time of his birth, the family was very well off, his father having inherited several properties in Cork and a fair sum of money in addition to holding the highly paid position of Collector of Rates for Dublin. Within a few years, however, John Joyce lost his lucrative position; the family's debts grew rapidly, and by the time the last child was born all of the properties were gone.

Before those hardships arrived, six-year-old James was enrolled in the prestigious Jesuit-run Clongowes Wood College in County Kildare, his father being determined that his eldest son would receive the very best education to be had in Ireland. After three years, though, his father was no longer able to pay the fees, and Joyce was placed in the far less prestigious Christian Brothers school on North Richmond street (mentioned in the opening lines of "Araby") for two years until his father managed to arrange a free place for him at another Jesuit school, Belvedere College in Dublin. He excelled in school, earning several national academic prizes. Between 1898 and 1902 he studied languages at University College, Dublin, causing a sensation when he published a review of Henrik Ibsen's When We Dead Awaken that received a complimentary response from the celebrated Norwegian playwright himself. Joyce was only 18 at the time.

After brief sojourns in Paris in 1902 and 1903, Joyce left Dublin for good in October 1904, accompanied by his lifelong companion Nora Barnacle, whom he had met and fallen in love with only months before. Years later, he would commemorate the day on which they first walked out together at Ringsend, June 16, 1904, by setting his latter-day epic Ulysses on that date. Today, legions of readers remember this day as Bloomsday, after that novel's quietly heroic central character, Leopold Bloom. Continuing the pattern established in the Joyce's youth, the couple moved often within and between a variety of European cities, including Paris, Rome, Zurich, and Trieste. Their financial situation was often dire, owing in some part to Joyce's astonishing recklessness with whatever money came their way; their second child, Lucia, was born in the pauper's ward of a Trieste hospital. With the exception of two brief visits, in 1909 and 1912, Joyce never set foot in his native city again.

Joyce published his first book, a slim volume of poems, Chamber Music, in 1907, but his fiction had a long and difficult path to publication. Early drafts of his first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, were begun as early as 1904, a decade before the greatly revised book saw print. Meanwhile, Joyce began seeking a publisher for Dubliners as early as December 1905. Within a few months he had signed a contract with Grant Richards for its publication, but the book would not appear in print until after a nearly a decade of often desperately frustrating negotiations with Richards and a series of other publishers and printers made nervous by the stories' often controversial subject matter and language. At one point in 1911, with the book still awaiting publication and the wrangling over it consuming more time and energy than he felt he could spare, an exasperated Joyce threw the manuscript of his still unfinished Portrait on the fire; fortunately, most of it was rescued by the Joyces' maid. At last, in June 1914, Dubliners was published in both England and America. A few months earlier, in February, the Egoist magazine had begun serial publication of Portrait, which ran until September 1915. After still further rejections and frustrations, the complete novel appeared in December 1916.

By this time Joyce was already at work on Ulysses, arguably his greatest achievement and unquestionably the book that made his reputation. Employing a remarkable and unprecedented range of narrative styles and techniques, Ulysses continues the story of Stephen Dedalus, the young would-be artist of his first novel, and brings into his company a genial father-figure, an unassuming advertising canvasser named Leopold Bloom, whose wanderings through the streets of Dublin on a single day in 1904 dimly echo the journey of Ulysses (or Odysseus), the hero of the Trojan War whose difficult voyage home is the subject of Homer's Odyssey. Like Portrait, Ulysses was serialized, in this case in the American magazine the Little Review between March 1918 and September 1920. Some issues were seized and burnt by the United States Post Office, which deemed them obscene. A trial followed, which resulted in the magazine's editors being convicted and fined, but narrowly escaping imprisonment. No doubt recalling the years of frustration preceding the appearance of Dubliners, Joyce feared the conviction would prevent any printer from taking Ulysses on. However, friends came to his aid, and the completed book was privately printed in a limited edition in 1922, with numerous reprints following over the next decade; an unlimited American edition finally saw print in 1934, with an English edition following two years later.

The publication of Ulysses in 1922 was a literary cause celebre: it delighted many and baffled and even disgusted others, but most players on the literary scene felt compelled to read and talk about the book. Far fewer, though, were inclined to rise to the considerable challenge of Joyce's next and final work, Finnegans Wake, begun in 1923, almost immediately following the completion of Ulysses, and published in book form in 1939, just two years before the author's death. "I imagine I'll have about eleven readers," Joyce wrote to a friend, and, while the estimate is certainly low, there are good reasons for his supposition. Few of the familiar landmarks readers have grown accustomed to are evident in this work. One cannot speak very easily about plot or characters, for instance, and the book is written in such a densely allusive and polyglot style that few attempt it without the assistance of the growing number of keys, guides, and annotations that have followed in its wake.

Harriet Shaw Weaver, Joyce's long-time benefactor, no doubt spoke for many later readers when she wrote, in response to an early excerpt, "But, dear sir...the poor hapless reader loses a great deal of your intention." Other readers were less polite. "Why can't you write sensible books that people can understand?" was his beloved Nora's characteristically blunt response; however, the book had and has its fervent admirers. Joyce's own commitment to his "book of the night," as he called it, is amply demonstrated by the fact that he persevered in the writing of it for sixteen years, despite an encroaching blindness that required him to write at times in an enormous longhand sometimes fitting only a few words on a page and to undergo a series of painful eye operations; meanwhile, it became increasingly apparent that his beloved daughter, Lucia, was suffering from schizophrenia, a condition that finally resulted in her being institutionalized in 1936.

Joyce died in Zurich on January 13, 1941, and was buried there in the Fluntern cemetery, but he is remembered best in the city he fled and recreated so magnificently in his work, Dublin.

OVERVIEW OF DUBLINERS

Dubliners is a short-story cycle, but unlike other such cycles, Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio (1919), for instance, or Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories, its stories are not linked by recurring characters, but by theme and setting, two elements that are intimately related in this collection. Joyce's initial intention, as he explained in a letter to the publisher Grant Richards, was to hold a mirror up to Dublin, to present as realistic a portrait of the city as possible by depicting Dubliners of various ages and from various walks of life. That portrait is, generally speaking, a disparaging one, but the negative tone is not consistently maintained throughout. By the time the volume concludes, with "The Dead" a story written slightly later than the others and which differs markedly from his earlier writing, a more sympathetic note is sounded, and we may glimpse there the far more generous vision that would characterize Joyce's later comic masterpiece, Ulysses.

SETTING

The title of the volume immediately draws our attention to the importance of the setting-both place and time unites these diverse stories. Joyce creates a panorama of Dublin by presenting a series of portraits of Dubliners in the grip of a moral paralysis he believed to be the city's overwhelming attribute. As he indicates in a 1906 letter to the publisher Grant Richards, My intention was to write a chapter of the moral history of my country and I chose Dublin for the scene because that city seemed to me the centre of paralysis...I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness and with the conviction that he is a very bold man who dares to alter in the presentment, still more to deform whatever he has seen and heard.

Dubliners, then, emerged from the author's dissatisfaction with the city of his birth, and his hope for the book was that it might show the indifferent public a necessarily unflattering portrait of itself.

Joyce's early years in Dublin, the years during which he wrote much of Dubliners, coincided with a pregnant pause in the political movement toward the Home Rule of which Irish nationalists dreamed. The downfall in 1889-1890 of the Irish Party leader Charles Stewart Parnell in the wake of a public scandal (he was named as co-respondent in a successful divorce suit and subsequently married the divorced woman, Parnell's long-time mistress, Katherine O Shea) appeared to have foiled once again the cause of Home Rule. A series of bills had been introduced beginning in the mid 1880s, culminating in the one that was passed finally, but not implemented, in 1914. At the time of the scandal, there appeared at least some possibility that a bill would be passed.

For many nationalists, the political vacuum would be filled in part by a rediscovery and celebration of Irish culture; the Irish Literary Renaissance associated with such figures as W. B. Yeats, Lady Augusta Gregory, and J. M. Synge gathered momentum at this point. There remained, however, much bitterness and frustration in the wake of the apparent failure of the nationalist cause. That cause would be powerfully and violently re-ignited by the Dublin rising of Easter 1916, but prior to that date, a sense of futility regarding nationalist aspirations is often in evidence in Irish writing. W. B. Yeats's "September 1913" (addressed, like Joyce's stories, to the public of Dublin, it was printed in The Irish Times) contemptuously compares Dublin's middle classes with the great nationalist heroes of a Romantic Ireland that is dead and gone. Another poem, "To a Shade," addresses one of those heroes, the ghost of Parnell, bidding him not to walk the streets of the city that is unworthy of his presence. Joyce's disparaging portrait of Dublin as a city gripped by paralysis may also be viewed in light of the volume's broader historical moment. The paralyzed capital, and the nation that Stephen Dedalus, the central character in Joyce's Portrait, perceived as a series of entrapping nets would be, in Yeats's famous words changed utterly by the political events of the coming years.

THEMES AND CHARACTERS

While there are no recurring characters in Dubliners, Joyce does appear to have envisioned the collection as a single work that would expose the city's crippling moral paralysis. His examination of Dublin's condition was carried out according to a plan he laid out for the publisher Grant Richards. Each stage of life, from childhood to maturity and public life was to be represented by one of four groups of stories in the collection. The first group, which Joyce described as "stories of my childhood," would comprise "The Sisters," "An Encounter," and "Araby;" the second group, stories of adolescence, would contain "The Boarding House," "After the Race," and "Eveline;" the third group, stories of mature life, would be "Clay," "Counterparts," and "A Painful Case;" the final group, stories of public life in Dublin, would contain "Ivy Day in the Committee Room," "A Mother," and "Grace." Three stories were not yet included in this plan, but their placement in the volume and their subject matter would lead us to place "Two Gallants" among the stories of adolescence and "A Little Cloud" among the stories of mature life. "The Dead," while having a strong thematic link with the preceding stories, is still so different from them in terms of its structure and its tone that it is probably best not forced into a scheme devised before its completion.

The first three stories in the volume, the stories of childhood, depict a series of initiations, as a result of which innocent youths come to a recognition of the grayness and decadence of their world. The first story, "The Sisters," is particularly grim in tone, focusing as it does on the death of Father Flynn, an elderly Catholic priest to whom the story's young narrator had been devoted. Despite the priest's advanced age and virtual incapacity, the boy was clearly very fond of him; the priest instructed the boy as to the rituals and mysteries of the Catholic Church, showing him the various vestments to be worn for different ceremonies, drilling him on questions of canon law and impressing upon him the significance of the rites surrounding the Eucharist and the confessional. Enchanted with the power and responsibility he believes Father Flynn possesses, the narrator is only barely aware of the frail man behind the vestments. With the priest's death, though, comes further knowledge, which dawns upon the boy as he listens to the exchange between his aunt and the priest's sisters. What we hear is a gradual but only partial unveiling of some dark secret of the priest's, as platitudes give way to more suggestive remarks. He was a disappointed man who had once broken one of the chalices he had taught the boy to regard as sacred, an incident that seems to have affected his mind. Before the story fades out inconclusively (the final ellipses underscoring its lack of closure), the boy has heard of an incident in which Father Flynn disappeared and was discovered sitting up by himself in the dark in his confession-box, wide awake and laughing softly to himself.

What exactly this means, no one in the story ventures to say, beyond Eliza Flynn's vague conclusion that there was something gone wrong with him; however, we know the impact upon the boy is a profound one. This is a Father Flynn he has never seen before: not the awesome practitioner of sacred rites, but a tormented, perhaps even insane man whose priestly dignity has been shattered, whose laughter in the darkened confession-box hints at some other, grimmer secret the boy has never even known existed.

"An Encounter" and "Araby" similarly portray young boys who fall from innocence: the eponymous encounter between the child narrator and a pedophile brings an abrupt end to what had been a youthful adventure, a day's escape from school. The young narrator of "Araby" experiences his first love in the most high-flown romantic terms, imagining himself a questing knight in the service of his lady until he reaches the end of his quest, the splendid bazaar from which he will retrieve a gift for her, only to have its tawdriness pierce his romantic illusions.

The characters we see in the stories of adolescence are more in the grip of the general paralysis, but not completely so. What these stories tend to portray are the ways in which that paralysis advances, as the Dubliners they describe resign themselves to their disappointing adult lives. An emotional paralysis becomes literal in "Eveline," as that story's central figure finds herself unable, even at the very moment of her escape, to board the ship that would have taken her away to Buenos Aires with her fianc�, choosing instead to return to a miserable life as daughter-cum-servant to an abusive father she fears. The well-traveled and experienced fianc�, Frank, an Irish sailor, represents for Eveline the romantic possibilities that dreams of Araby held for the young boy in the earlier story, but this trapped Dubliner finds herself unable to move toward the promised freedom. "The Boarding House" is another tale of entrapment, in this case the entrapment of Bob Doran into an almost certainly unhappy marriage by his landlady, Mrs. Mooney, and her quietly colluding daughter, Polly. Striking similar notes, both "After the Race" and "Two Gallants" feature characters (Jimmy and Lenehan) whose thoughts are disquieted by the recognition that their lives are not and will never be as they would have wanted.

The stories of mature life all focus on characters trying to contend with the failures of their lives. Perhaps the most moving of these is "Clay," in which the central character, Maria, copes by simply failing to see her life as it is, a pitiable strategy mimicked in the story's style, which resembles that of a children's story ("Maria was a very, very small person indeed but she had a very long nose and a very long chin."). The bright tone stands sharply at odds with the gloomy content of the story itself: Maria is an aging, lonely woman, separated from her feuding brothers and working, as a result, in a seedy Dublin laundry. As jolly as the narrator tries to make her life appear, it is not the life Maria wants. Her eyes sparkle with disappointed shyness when Lizzie Fleming jokes that she will choose the ring (signifying marriage) in the divination game to be played that night, All Hallows Eve. And when she sings her song, "I dreamt that I dwelt," she significantly omits this second verse, which begins, "I dreamt that suitors besought my hand." What the story's strangely bright tone and children's-story style suggest is the aging Maria's own attempt to imagine herself in an idyllic girlhood awaiting a romantic release into a happy adulthood: the sad realities of her life are veiled by a barely-sustained fantasy (so that her eyes sparkle, but with a disappointed shyness rather than joy). She knows, but does not quite admit to herself, that she will not choose the ring; her true fate is signaled by the token she actually chooses and of which no one in the story will speak: clay, the token of death.

Fragile though they may be, Maria's sustaining beliefs are left intact at the end of that story. In "A Painful Case" we witness the devastating effect upon Mrs. Sinico when her love for the selfish and emotionally stunted Mr. Duffy is spurned. Her suicide four years after, which Mr. Duffy recognizes as the outcome of the break-up, shatters his illusions about himself as a great or even a good man. The egotist who had once believed that in Mrs. Sinico's eyes he would ascend to an angelical stature comes to recognize himself, too late, as an outcast from life's feast. The remaining stories in this group, "A Little Cloud" and "Counterparts," portray trapped and frustrated men who finally take out their frustrations on their own sons, brutally so in the case of Farrington in the latter story, implying in both cases a continuance of the debilitating legacy among the next generation.

The final group of stories, dealing with public life, expands the focus to a community in the grip of the general paralysis, with the stories exploring, in turn, political life ("Ivy Day in the Committee Room"), cultural life ("A Mother") and religious life ("Grace"). The corrupt politicians who gather on October 6, the anniversary of Parnell's death ("Ivy Day"), are the nationalist leader's sorry successors. Hynes's hackneyed poem, "The Death of Parnell," alludes to a fell gang of modern hypocrites who laid their leader low, but Joyce makes it plain that one would not have to look beyond this committee room to find a gang of hypocrites in the story's present. "A Mother" paints an unpleasant picture of Dublin's cultural life, contrasting the middle-class pretensions of Mrs. Kearney with the second-rate concert series in which she has involved her daughter. The Irish Renaissance too appears a sham here-less a cultural renaissance than a shallow fad, with the daughters of the wealthier families hiring Irish teachers so their daughters can send Irish picture postcards back and forth to each other. "Grace" depicts a city whose spiritual life is hopelessly corrupted by parochial and material concerns, culminating in Father Burdon's description of himself during the retreat as a "spiritual accountant." Mr. Kernan's path toward redemption has tellingly little of the spiritual about it.

The final story in the volume, "The Dead," is once again an exploration of Dublin's woeful moral state, but Joyce is far more generous and sympathetic in his portrait of the Dubliner at the center of this long short story. Like Mr. Duffy in "A Painful Case," Gabriel Conroy is shocked into a recognition of himself as an unhappy exile from life. However, Gabriel is a far more complex character than Duffy, and his pretensions are balanced by his good heart and sincere (if inadequate) love for his Gretta. Throughout the night of the party we see evidence not only of Gabriel's sense of intellectual superiority, but also of his awkwardness and self-doubt, despite all of which he does his best to contribute to the success of the Misses Morkans annual gathering. Where Duffy's self-recognition may appear merely pathetic, Gabriel's is likely to strike us as tragic.

LITERARY QUALITIES

Discussions of Joyce's earlier fiction, Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, frequently center on those moments in which characters achieve an "epiphany" or sudden revelation. The term, which Joyce used to describe some of his earliest prose fragments, means, literally, a showing forth. In the Christian calendar, the feast of the Epiphany commemorates the arrival of the Magi in Bethlehem to worship the newborn Christ; the epiphany is the showing forth of Christ to the three kings. For Joyce, the word has a broader meaning, standing for a moment of insight, when a truth is suddenly revealed. Most of the stories in Dubliners do feature discernible epiphanies: the young boy in "Araby" clearly has a poignant moment of insight about his world as the bazaar lights dim, for instance, and Gabriel Conroy undergoes a terrible self-examination in the final moments of "The Dead." In other cases, such as that of Maria in "Clay," the insight eludes the character and falls instead to the reader. Either way, another instance of Dublin's paralysis stands revealed.

Joyce told Grant Richards that he had written Dubliners, in a famous phrase, in a style of "scrupulous meanness," his intent being to hold up to Dublin a relentlessly true image of itself. While the stories are remarkably pared down in style, their "scrupulous meanness" should not blind us to one of their most distinctive features: the manner in which they bring a distinctly Irish English to the page. One cannot read a line such as this one of Lily's in "The Dead," "The men that is now is only all palaver and what they can get out of you," without hearing its Irish lilt. Joyce's influence on Irish writing in English during the 20th century was considerable, and it is not without reason that there have been so many recordings of these stories.

SOCIAL SENSITIVITY

In a 1905 letter to Grant Richards, Joyce related his surprise that "no artist has given Dublin to the world," despite its antiquity, its size, and its status as the second city of the British Empire. Dubliners, an attempt to fill this void, certainly casts a critical eye over its subject, but that Joyce wanted so badly to "give Dublin to the world" indicates that his aim goes well beyond merely excoriating the city of his youth. That Joyce's attitude toward the city is a complex one is hardly surprising. He did, after all, feel compelled to leave the city for good, only to devote a life-long self-imposed exile to writing about the place in the most painstaking detail. Dubliners, then, is a powerfully ambivalent volume, characterized at least as much by Joyce's frustration with the shortcomings of the city and its inhabitants as his sympathy for and powerful attachment to them both.

The volume is not uniformly generous toward all of the Dubliners contained therein: he certainly does ridicule the pretensions of Mrs. Kearney in "A Mother," for instance, and the vain politicians of "Ivy Day in the Committee Room," among others; however, the sympathetic notes struck in stories such as "Araby," "Clay," and "The Dead" overwhelm the satirical ones heard elsewhere in the volume and are more indicative of the direction Joyce's work will take in the future, particularly in his great human comedy, Ulysses. Dubliners suggests how profoundly individuals can be shaped and influenced, both for good and ill, by the places they inhabit. The stories themselves are full of characters who are in various ways stifled within Dublin's social, political and religious institutions. However, those same institutions left an equally deep mark on the author, a Dubliner who left, but carried the city always in his imagination.