Contents

PREFACE

Over the decades, language teachers and others concerned with language teaching have witnessed multitudes of methods of and approaches to language teaching. However, it is only in the recent years that the English language curriculum in Bangladesh has gone through notable changes.

The changes were brought about through several means. The National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) designed a communicative syllabus for the secondary level, published the guidelines to produce textbooks, and encouraged the teachers to carry out the teaching according to the syllabus. It has also produced communicative textbooks for classes 6 to 12. Furthermore, it has revised the evaluation policy and developed several assessment tools and examination formats to help measure students' ability to use English in communication.

However, students are still far away from the expected levels of proficiency.

Inconsistencies were mostly found at the classroom implementation level. The teachers of English somehow failed to adhere to an appropriate methodology to carry out teaching and learning.

Some deficiencies were noted at other levels as well. For example, curriculum did not address the students' and teachers' existing communicative competence, their proficiency levels, and the hopes and hurdles they broght with them to the class. As for the examinations, questions were still set from the set textbooks, which generally may not focus on communicative aspects of language use, etc.

My Ph.D. dissertation presented here puts the above conditions in perspective, and discusses the different components and stages of the existing English language curriculum at the secondary level of education in Bangladesh.

The early inspiration for this work came from my days in Bandura Holy Cross High School, Dhaka, where I was taught English by one of my favorite teachers Late Bro. Donald, C.S.C, who developed a methodology of his own, which proved appropriate to carry out teaching and learning English in our situation effectively. Also during my days in Savar Model Academy, Dhaka, where I taught English to the students of classes 9 and 10 in 1997, this interest further grew in me. While learning English, I found that many of my teachers treated me as an empty receptacle. While teaching English, however, I saw many teachers still failed to address students' existing communicative competence.

However, the major part of encouragement to take up this topic for research came from Professor A.R. Fatihi, Department of Linguistics, Aligarh Muslim University, India, presently Visiting Faculty at Cornell University, U.S.A. He not only gladly assumed the responsibility to supervise my research and guided me with great insight, but also helped and mentored me in every respect relating to my research and personal life. It was his painstaking, patient, and continuous guidance that enabled me to write and complete this dissertation. So, I am indeed grateful to Professor Fatihi.

In preparing this thesis, I took help from many others. At first, I should express my deep sense of gratitude to Professor Mirza Khalil Beg, Chairman, Department of Linguistics, A.M.U., who helped me in many ways and provided all possible facilities from the department.

I consider it my pleasant duty to thank all the teachers and staff of the Department of Linguistics, staff and officials of Maulana Azad Library, officials and staff of IER Library, Dhaka University, who helped me in all possible ways. My special thanks go to Mr. Gulam Hussain Bhuyan, Deputy Librarian, IER Library, Dhaka University, who placed all the necessary written materials in my disposal. My special thanks also go to Dr. Syed Ikhtiar, Lecturer, Department of Linguistics, AMU, whose suggestions were very valuable in the final stage of my work.

My thanks also go to those students and teachers of Mirpur Monikanchan High School, Bandura Holy Cross High School, Bogra Cantonment Public School and College, Talifuzul Quranil Karim Senior Madrasah, and Unail Alim Madrasah, who eagerly came forward to help me in the collection of information, through interviews, etc.

I wish to express my deep regard and profound love to my parents, parents-in-law, brothers and sisters, who always motivated me to complete the thesis.

Finally, a sense of obligation beckons me to mention the name of Hasi, my wife, who kept me away from all the family chores and remained a constant source of inspiration all the time during these years. She not only gave me opportunity to work, but also did a lot -- sometimes read parts of my work, sometimes listened attentively while I read it to her, sometimes typed it for me. All these she did in addition to her regular office duties as a scientific officer of INST, AERE, Savar, Dhaka, along with raising our daughter, Sememe, who barred me many times from the work by clinching my pen and clicking the keyboard, but always pepped me up.

Md. Kamrul Hasan

LIST OF SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED

| Symbols/ abbreviations | Expressions |

| CC | Communicative Competence |

| CLT | Communicative Language Teaching |

| DM | Direct Method |

| EFL | English as a Foreign Language |

| EFT | English For Today |

| EL | English Language |

| ELTIP | English Language Teaching Improvement Project |

| ELT | English Language Teaching |

| ELL/T | English Language Learning and Teaching |

| ENL | English as a Native Language |

| ESL | English as a Second Language |

| FL | Foreign Language |

| GTM | Grammar Translation Method |

| L1 | First Language |

| L2 | Second Language |

| LAD | Language Acquisition Device |

| MEB | Madrasah Education Board |

| NCTB | National Curriculum and Textbook Board |

| S | Student |

| SL | Second Language |

| SS | Students |

| T | Teacher |

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

|

Table No. |

|

Page No. |

|

2.1 |

Student’s proficiency levels as viewed by students |

19 |

|

2.2 |

Student’s proficiency levels in four basic skills as viewed by students |

20 |

|

2.3 |

Students proficiency levels as viewed by teachers |

21 |

|

2.4 |

Extent of use of English in classroom discussion as view by students |

23 |

|

2.5 |

Extent of students' participation in pair/group work as viewed by students |

23 |

|

2.6 |

Extent of practising four skills as viewed by students |

24 |

|

2.7 |

Students' use of English in real life as viewed by students |

25 |

|

2.8 |

Extent of students' use of English as viewed by teacher |

26 |

|

2.9 |

Teachers' proficiency levels as viewed by teachers |

31 |

|

2.10 |

Extent of teachers' use of English as perceived by teachers |

32 |

|

3.1 |

Grammatical syllabus |

41 |

|

3.2 |

Collaborative balanced syllabus |

45 |

|

3.3 |

Extract from NCTB syllabus for class 10 |

67 |

|

3.4 |

Number of new vocabulary to be introduced in different classes |

68 |

|

5.1 |

Students' perception of EL needs |

128 |

|

5.2 |

Students' EL needs as viewed by teachers |

130 |

|

5.3 |

Students' perception of needs of language skills |

133 |

|

5.4 |

Extent of practising four skills as viewed by students |

134 |

|

5.5 |

Extent of use of English in classroom discussion as viewed by students |

135 |

|

5.6 |

Extent of students' participation in pair/group work as viewed by students |

136 |

|

5.7 |

Students' view of how they learn more |

137 |

|

5.8 |

Teachers' knowledge of different methods |

138 |

|

5.9 |

Teachers' arrangement of use of language for communication |

140 |

|

5.10 |

Students' participation in pair/group work as viewed by teachers |

141 |

|

5.11 |

Teachers' preference of different aspects of language learning/teaching |

142 |

|

6.1 |

Techniques of testing language skills |

149-150 |

LIST OF FIGURES USED

|

Fig. No. |

|

Page No. |

|

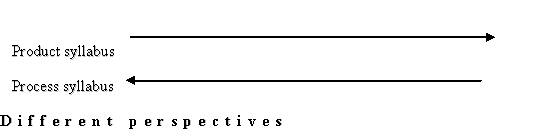

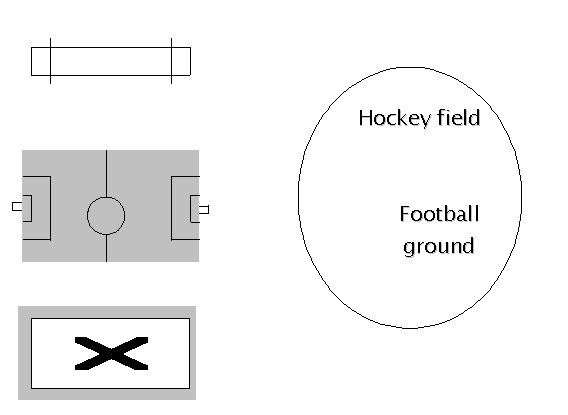

3.1 |

Product and process Syllabuses |

40 |

|

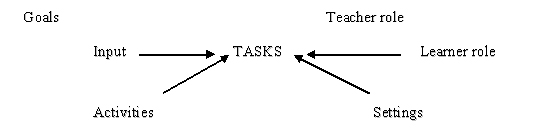

3.2 |

Components of communicative task |

47 |

|

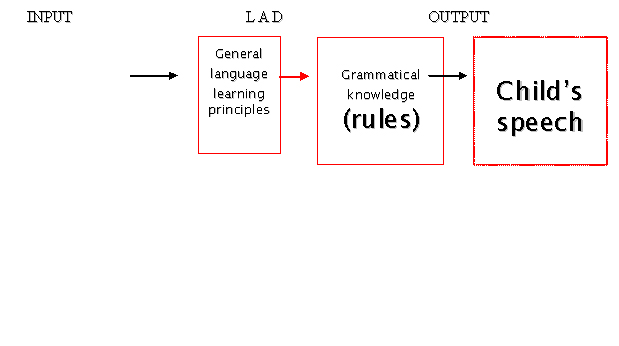

3.3 |

Language acquisition device (LAD) |

53 |

|

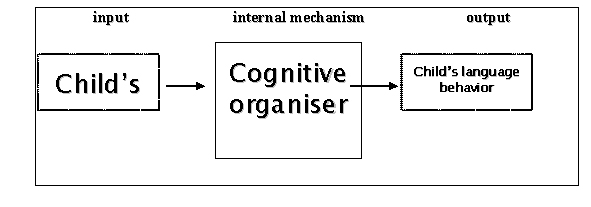

3.4 |

The input/out system in language development |

54 |

|

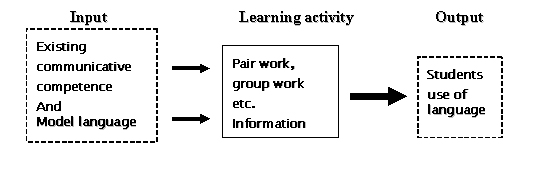

5.1 |

Teaching language as communication |

109 |

|

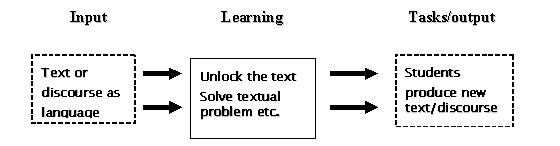

5.2 |

Teaching language as discourse |

110 |

|

5.3 |

Colour chart |

111 |

|

5.4 |

Mariam's family |

112 |

|

5.5 |

Imperative symbols |

113 |

|

5.6 |

Story telling activity |

120 |

|

7.1 |

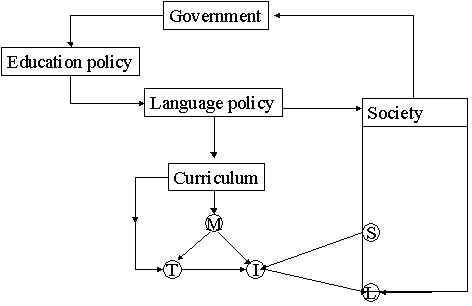

Integration of four levels of curriculum development |

170 |

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 World English

The global distributions of English are often described in terms of three contexts. These are English as a Native Language (ENL), English as a Second Language (ESL) and English as a Foreign Language (EFL). Thus the diffusion of English throughout the world is seen in territories, viz., ENL territories, ESL territories and EFL territories (Braj B. Kachru in Koul N. Omkar (eds.) 1992: 2 -3, Crystal D 1995: 107, McArthur 1996 p: 327). In ENL territories English is spoken as the first or often as the only language. Here ENL refers to the mother tongue variety of English. In countries like the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, English enjoys the status of native language. In ESL territories many people use English for various purposes. English plays a vital role - official, educational, and other. Here (ESL) English is an institutional language. It has an institutional variety as well. English is used as a second language in almost all the former British colonies. Some of the major features of ESL countries are as follows:

- English is one of the linguistic codes of the country.

- It has acquired an important status in language policy.

- It is learned at schools to an adequate level for national and/or international use.

English is used as a second language for many purposes in such countries as India, Nigeria and Singapore. A person's chronological second language, however, in many cases becomes the functional first language of adulthood. Under such conditions as migration, an original second language may become the person's only language.

In EFL situations, however, English may be more or less prestigious, and more or less welcomed in particular places. Many people learn it for occupational purposes and/or for education and recreation. English is taught as a foreign language in many countries like China and Japan.

1.2 ELT in Bangladesh: A historical sketch

McArthur (1996) locates Bangladesh in the ESL territories. However, in elsewhere he says in Bangladesh English is neither a second language nor it is a foreign language. Ibid. To give a clear idea about the ELT context of Bangladesh, the following sections present a historical overview of ELT in Bangladesh.

1.2.1 Pre-colonial period

English was first introduced in the South Asian subcontinent in the18th century when the Mughal Empire was on decline. However, it paved the way towards the sub-continent following the path of Portuguese in the 15th and 16th centuries after Vasco de Gama discovered the sea-route to India in 1498.

At that period although Portuguese was used as the 'lingua franca' -- a common language among the people of both Europe and the sub-continent, after the Englishmen formed their own company, English became the language of communication of the elite people of the both sides. And as it was used only by the elite groups, English never became a Creole or Pidgin. Rather a fairly standard variety of it entrenched among the select elite people. Some later-days' varieties like 'shahib variety', 'Bulter variety' etc. are exactly what their names imply (Dil, S.Anwar 1966 in Dil, S. Anwar (ed) p-199; Krishnaswamy and Sriraman 1995).

1.2.2 Colonial period

It was Lord Mcaulay's minute of 1835 that, for the first time, addressed the necessity of teaching English in the South Asian subcontinent. (see Krishnaswamy and Sriraman 1995; also see the papers By Dutta, Selim and Mahboob, and Choudhury in Alam F. et al (eds.) 2001). However, a considerable amount of preparatory work had been going on since the consolidation of the activities of the East India Company in eighteenth century. Christian missionaries entered India as far back as 1759, and 1787 despatch welcomed the efforts of Rev. Swartz to establish schools for the teaching of English. That the socio-historical context for the dominance of English was gradually taking shape at least by the end of 18th century is supported by The Tutor, the first book written to teach English to the non-Europeans. It was published in Serampore in Bengal. The author John Miller himself printed this book in British Bengal in 1797. (Howatt 1984)

The early missionary activity also introduced processes of standardisation of unwritten and tribal languages. Although in most cases missionaries did not teach English, they translated the Bible into the native languages in the Roman orthography. Non-native English speakers thus created the norms of several local languages. The association of these languages with Roman orthography has today introduced an important dimension in the struggle to evolve writing systems of these languages.

Macaulay in his Minutes of 1835 spoke of the importance and usefulness of the education that would be given to the natives through the medium of English. He mentioned two objectives of such education. The first was to create through this education a class of natives who, despite their blood and colour, would be English in culture and be able to "interpret" between the rulers and the subjects. The second was to create a "demand" for the European institutions. Clearly both the objectives were designed to serve the interest of the Masters, not of the subjects. "When it comes," he said, "it will be the proudest day in English history." (Macaulay 1835 quoted in Chaudhury 2001)

Macaulay believed that it was necessary to introduce English in India, - Indian people 'cannot at present be educated by means of their mother tongue' (Macaulay 1835 qouted in Aggarwal 1983:5). He felt that Indian languages and literature were of little intrinsic value and Indian histories, astronomy, medicine etc., were full of errors and falsehood. The continuance of Sanskrit and Arabic in Indian education system, Macaulay was convinced, could only harm both the Indians and British government. He recommended the closure of Sanskrit and Arabic schools and a withdrawal of all financial support from these institutions. No books were to be printed in Sanskrit and Arabic. He said: We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from western nomenclature and to render them by degree fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the populations (quoted from Macaulay 1835 in Aggarwal 1983: 11)

The aims and objectives of teaching English were thus very clearly defined in the middle of the nineteenth century. Das Gupta (1970: 40-45) says that to prove that English language, culture, literature, and people were superior to anything Indian was the primary purpose for introducing English as the medium of instruction and as a subject of study.

As early as 1823, Ram Mohan Roy had written to Lord Amherst that the Sanskrit system of education could only keep the Indians in darkness. In Mumbai, on the other hand, the emphasis was on the vernacular languages. Since governmental support was available only for English, the movement for the dominance of English became more rigorous.

Wood's despatch of 1854 marked a position for vernacular languages, at least in policy. Although wood recognised the role that the vernacular languages can play in mass education, the superiority of British language and culture remained unquestioned. The despatch said, 'we look, therefore, to the English language and the vernacular languages of India as the media of diffusion of European knowledge... (see Agnihotri and Khanna (eds.) 1995: 17). English thus was to be the language of the select elite, used in power and prestige; 'vernacular' languages were for the masses to be used in peripheral domains.

In 1837 English and vernacular languages had already replaced Persian in the proceedings of the law courts - English in the higher and vernacular languages in the lower courts. Thus, in both education and law courts, language became a marker of two separate levels of social operation -the upper level for English, the lower level for the vernaculars. The policy of administrators consciously promoted the association of English with the status of privilege...(quoted from Das Gupta 1970: 43-44 in Agnihotri and Khanna (eds.) 1995: 18).

In fact, a large-scale literary and linguistic engineering was done for the permanence of British imperialistic expansion in India. The consolidation of English literature as a discipline and the introduction and establishment of English as medium of instruction and as a subject of study were a part of this engineering. (cf. Rajan, S. 1993: 9-11)

The story of English in the remaining period of colonial rule can be described in terms of a few landmarks such as the establishment of universities in Kolkata, Mumbai and Channai in 1857 and in Dhaka in 1920 resulting selective education and training in administration, imparted through English, the Indian University Act (1904) and the Resolution on Educational Policy (1913).

We notice three broad developments with regard to English education during the British rule:

- Levels of attainment in English: During the early years (1600 -1800) the high variety called the shahib variety was imitative and formal. During the later years (1850 -1947) more varieties (from very high to very low) appeared.

- Interaction with vernacular languages: A number of words of vernacular origin were absorbed in English, e.g., Brahmin. Coolie, jungle, and so on.

- Methodology: Language studies in colonial period and before colonial period were based on literature and grammar and the means of studies was the grammar-translation method. The spoken component of the language was not practised. The emphasis was given on accuracy and full sentence.

1.2.3 Post colonial period

The question of language loomed large after 1947 with the creation of two nation states- India and Pakistan. India opted for Hindi and in Pakistan, a "Muslim nation state" attempts were made to make Urdu -the " Muslim language (?)" -the state language. In the face of violent protest from the East Pakistan, culminating in the tragic shooting death on February 21, 1952, both Bengali and Urdu were made the state languages of Pakistan. In these circumstances, neither Bengali nor Urdu but English became the common language for communication between East and West Pakistan. Thus in Pakistan period English enjoyed the status of second language and it was taught as a functional language at secondary schools in Pakistan (1962 report of Curriculum Committee).

After the liberation, Bangladesh made Bengali the state language and the status of English was drastically reduced. Bengali replaced English in all official communications except those in foreign missions and countries and in armies, where English is still used as official language. Also in secondary and higher secondary education Bengali became the only medium. Attempts were made to translate English books into Bengali to meet the needs of books in different subjects. However, English was still a compulsory subject through secondary and higher secondary levels. From B. A. level English was withdrawn as a compulsory subject. Moreover, the Bangla Procolon Ain (Bengali Implementation Act) of 1987 ceased English to be used as an official second language. The result was drastic. The standard of English fell to the abysmal depth in public schools and universities. But what we experienced in later days is the frustrating reality that Bengali has failed to be an adequate medium of education in the higher levels. And in recent years a large portion of the population have been going abroad for jobs, education etc. and this made the Government rethink the emotional withdrawal of English from B. A. level that was made in 1974. Now English has again come back as compulsory subject in B. A. level, even for science and commerce graduates.

1.2.4 The present state

The withdrawal of English as a medium of education from public schools led growing number of parents to send their children and wards to English medium schools, where students can prepare for English Cambridge or O' and A' level examinations. Graduates from these schools often remain very weak in Bengali but comparatively better in English. Many of them prefer to get admitted in foreign universities, sometimes in the United States.

The private university act 1992 allowed the setting up of a good number of universities, where English is used as the medium of instructions. These universities give special emphasis on English because English is in much demand and to attract students and their money. Editors of Revisioning English in Bangladesh (a book in which emerged essays from the biennial conference 1996 held in the Department of English, Dhaka University about rethinking the status of English in Bangladesh) say that students from these universities, though have the same level of proficiency as those from the public universities while get admitted, at the end of a four year stay acquire a higher level of proficiency and are often recruited by the multinational organisations who look for strong English language proficiency. (Preface to the book)

Now the growing number of private universities, English medium schools and tutorial centres that offer courses of different foreign universities and institutions and job advertisements of different local and multinational organisations and agencies mark the status of English in Bangladesh.

However, language had been and still has been a marker for separate levels of social operation. There are three education systems at secondary level in Bangladesh and existence of these three systems marks the divisive lines between three classes of people - the rich, the middle class and the poor. Bengali represents the mainstream as in the public schools and colleges it has been the medium of education. The other two streams are English medium schools and madrasahs. In madrasahs though Bengali is the medium of instruction, Arabic has a prestigious place there. While the middle class people opt for (or are compelled to opt for) Bengali (in public schools and colleges), the poor (are compelled to) and the rich choose Arabic and English respectively. Thus, education in Bangladesh, instead of bringing people together works as a divisive force (Choudhury S. I.: "The state and people" appearing in The Daily Star in the special supplement on 'Amar Ekushey', 21 February 2003).

Choudhury S. I. in his paper "Rethinking the two Englishes" rightly said, " The acquisition of English happens to be an instrument for gaining both power and prestige and to limit its knowledge to a section of society would be to deprive others of a right." (In Alam F. eds. 2001: p-16)

1.3 English in the curriculum of Bangladesh

1.3.1 ELT needs in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh a number of foreign languages like Arabic, French, Japanese, Persian, etc. are taught at universities. But for a number of reasons only one foreign language i.e., English is taught as a compulsory subject across primary, secondary, higher secondary, and even the tertiary levels. To mention some: it is used as a lingua franca for global communication. For this, to deal with different international bodies and organisations working within and outside the country people need English. Furthermore, English gives them easy access to the ever-expanding knowledge of science and technology, arts and education, innovations and discoveries as all the works - books, journals, reports, research-findings - are available in English. It is the language of information technology that has, in fact, made the whole world a global village. English is the language of the international labour market. English for occupational/ professional purposes can help find jobs in other countries. In the local labour market also English has a prestige. Knowing the language of a country, say Saudi Arabia, may help one be enable to work in that country or in a country where that language (here Arabic) is spoken. But knowing English enables to work more or less in the whole world.

So, English is a surviving language for some people, e.g., those who are seeking or doing jobs in foreign countries. Some others use it as a stairs towards good fortune. And yet some others see it as an attribute of prestige. Whatsoever might be the Bangladeshi people's attitudes towards English, it is uncontroversial that they need it. But just to state that English will be taught as a foreign language in Bangladesh does not adequately express the ELT needs of the country.

1.4 ELT policy in Bangladesh

It is the need of a national English language teaching policy that will address the practical needs for English in Bangladesh and determine what and how much English should be taught and for how long.

Making English study effective from primary to tertiary levels needs a lot of inputs and resources like trained teachers, communicative teaching materials and financial, infra-structural and management facilities. These resources are not equally available or favourable for learning English in all the educational institutions of the country. In some urban elite schools these inputs are mostly available and the school leavers can use English, more or less, in their further study or in jobs that they choose. But most of the rural schools lack in some or almost all these resources. As a result, teaching-learning English in these schools cannot be done in the way it should be done. In most cases, learning English means rote learning of grammar rules and textbook contents even without understanding.

Also students in these disadvantaged schools are not aware of the aims and objectives of studying English, except that they have to appear the examinations in this subject. Consequently, English often seems to be a heavy unnecessary burden to them. The time, energy and money spent on teaching-learning English at these schools are often wasted. Of all the students from class 1 to 14, some students have some benefits, no doubt, but some others do not need to study it all these years.

Under National University, to which all the colleges (government and non-government) are affiliated, all the B. A., B. Sc. and B. S. S. pass and honours students have to study a compulsory English course - General English, of 100 marks. But Many students in this level do not need this General English. For example, students doing honours in history, philosophy, sociology, etc. need English - but not general, grammar-based English. They need the kind of English that will facilitate their studies. Similarly, the students studying medicine, science and technology, business, etc. will need English for specific purposes, viz., English for nurses, English for doctors, scientific English, business English and so on. This is because the general English courses cannot cater the specific needs of these specialised areas of study.

1.5 The existing curriculum in Bangladesh

There are three levels or stages of secondary education in the combine education curriculum. These are - Junior Secondary, Secondary and Higher Secondary levels. In junior secondary level there are two sub-systems of education. These are -

- General Education Sub-System

- Madrasah Education Sub-System

In Secondary and Higher Secondary Levels, there are three sub-systems -

- General Education Sub-System

- Madrasah Education Sub-System

- Vocational Education Sub-System

There are seven general education boards for the arrangement of examinations and certification of the general education sub-system. The National Curriculum And Textbook Board (NCTB) is responsible for the preparing curriculum and syllabus for the seven general education boards. The responsibility of the preparation of curriculum and syllabuses for the madrasah education sub-system and vocational education sub-system is assigned to the Madrasah Education Board and Technical Education Board respectively. They are also responsible for arranging examinations and for certification of their students.

1.5.1 The National Curriculum

In 1980s, the government of Bangladesh took initiatives to prepare and modernise the curriculum in order to meet the needs and challenges of the time. However, the existing curriculum proved inadequate for the changed world situation in 1990s. Therefore, the necessities to make the curriculum appropriate for the present situation have been felt, and some efforts have been taken to fulfil these needs.

In order to prepare a curriculum for the Secondary and Higher Secondary education and for the proper implementation of such a curriculum a Curriculum Preparation and Implementation Taskforce was formed. This taskforce proposed a framework for the national curriculum.

A curriculum committee consisting of eminent educationints and education administrators of the country was formed under the leadership of the Education Secretary. On the basis of detail discussion at a workshop on 6 and 9 November 1994 in the presence of eminent educationints and education administrators of the country the framework for the combine education system was finalised.

With the collaboration of National Curriculum and Textbook Board, the Higher Secondary Education Project, Madrasah Education Board and Technical Education Board, the Curriculum Committee prepared the new reformed curriculum.

For the circulation for teachers, students, textbook writers and those related to teaching the reformed curriculum was published in December 1995. It included syllabus checklist and guidelines for all concerned with the teaching and learning of English and other curricular subjects.

1.5.1.1 Place of English in the national curriculum

English is taught as a compulsory subject throughout all the levels of all the sub-systems. Bengali, the mother language, is also taught as a compulsory subject. In general and vocational education there are two compulsory papers of English and two papers of Bengali of 100 marks each, whereas in Madrasah education language syllabus in junior level differs from those of secondary and higher secondary levels. In junior secondary level Madrasah students read two compulsory papers of Arabic, one paper of English and one of Bengali, in secondary level one compulsory paper of English, Arabic and Bengali each and in higher secondary level one compulsory paper of English and Bengali each.

As mentioned above, the Madrasah students study two compulsory papers of Arabic in junior secondary level and one compulsory paper of Arabic in secondary level, which the other sub-systems lack. Of coarse, there are options to some optional subjects for all the students. Students of humanities group of both madrasah and general education sub-systems can take English as an additional subject of two papers of 100 marks each. However, the syllabuses of the two subsystems vary considerably.

1.6 The scope of study

The present study aims to look at different components of the English Language Curriculum at secondary level (from class 6 to 10) in Bangladesh from Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) point of view. It will study the English curricula of two major sub-systems -- general education sub-system and madrasah education sub-system. As very few students are affiliated under technical education sub-system and there are only a handful of vocational institutes, this study will not focus on technical education. However, curriculum development is viewed as a continuous process, e.g., teacher development as a component of curriculum development continues throughout the entire career of some teachers and for years in some other instances.

As curriculum is a large and complex concept and though the term curriculum can be used in a number of different ways (see Nunan 1989a: P-14), the work will view curriculum development from a broader perspective to refer to all aspects of planning, implementation, evaluating and managing a language education programme. A rational curriculum is, however, developed by first identifying goals and objectives, then by listing, organising and grading the learning experiences, and finally by determining whether the goals and objectives have been achieved or not (Nunan 1989a from Tyler 1949).

Chapter 2 of this work will look at the issues related to learners' needs -actual and desired, in terms of the social strata they belong to. Their attitudes towards English and proficiency levels will also be addressed. The proficiency levels of the teachers from different backgrounds and their attitudes to English will also be discussed. These issues are, in many ways, the determinants of what is intended in the planning level.

In chapter 3, the existing English language curriculum of Bangladesh will be looked at in some details to see what happens in the planning level. Curriculum guidelines of the Bangladesh National Curriculum and Textbook Board including the syllabus checklist provided in it will be discussed. It will also look in the curriculum and syllabus of Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board. But prior to all these a theoretical framework will be proposed incorporating the findings of Chapter 2 and modern development in the field of linguistics, applied linguistics and language teaching. Insight from other related and interrelated disciplines like sociolinguitics, psycholinguistics and discourse analysis will also be taken into account. These are rather the abstract levels of curriculum process. Turning more specifically to the concrete levels of curriculum process, chapters 4 and 5 will look in the works of textbook writers and teachers. In fact, these are the people who are the consumers of other people's syllabus and are presented with curriculum guidelines and sets of syllabus specifications.

Once having been presented with the curriculum guidelines or syllabus specifications, the classroom teachers are required to develop their courses and programmes form these guidelines (Nunan 1989a, p.17). As their immediate focus is day-to-day schedule within the learners in the classrooms, they tend to see lessons and units as the basic building blocks of their programmes. Chapter 5 will look in how teachers of different institutes translate the intentions of curriculum planners into actions that is, the teaching methodologies adopted in different institutions. Prior to that, it will explore different approaches and methodologies of language teaching conceived so far as on a theoretical basis and employed throughout the history of language teaching.

In the same way, the textbook writers have to write each unit as guided by the curriculum designers. Teachers' immediate preoccupations are with learning tasks and with integrating these tasks into lessons and/or units (Nunan 1987, 1989a-17; Shavelson and Stern 1981). Chapter 4 will appraise the case of communicative textbooks for language teaching in Bangladesh situation. It will make an assessment of books used in schools and madrasahs of Bangladesh from communicative language teaching (CLT) point of view.

Teachers and textbook writers are, in fact, the consumers of other people's syllabus. Another consumer of syllabus specifications is the examiner who will set an end- course-examination. However, traditional examination system has failed to assess students' progress and attainment in terms of their ability to use English in real life. So, there is a need to develop appropriate evaluation tools and concerned parties should interpret and use them successfully. Chapter 5, will make an assessment of current testing scheme and evaluation policy of Bangladesh. Prior to that, it will theorise an appropriate evaluation system, which will address both students' progress and their attainment in examinations.

For the successful operating of any programme, it should be installed rightly before. For a thorough study of the infrastructure, resources available, teacher community and the students, who are the ultimate beneficiaries of the programme, chapter 2 will look in the social strata and proficiency levels of learners and teachers in an ethnographic manner. Chapter 2 of this work is furnished with the information about the proficiency levels of the two parties in relation to social stratification.

A syllabus checklist is something that illumines others' way to proceed. In recent years, however, curriculum development has been viewed as a collaborative effort between learners and teachers. This gave rise to the learner-centred approaches to language teaching. In this approach, information by and from learners is used in planning, implementing, and evaluating language programmes (Nunan 1989a P-17). However, no curriculum can be totally learner centred or subject centred. This study stays somewhere in the continuum.

CHAPTER 2

SOCIAL STRATIFICATION AND PROFICIENCY IN ENGLISH IN BANGLADESH

2.1 Social variables in Bangladesh

Proficiency in English varies according to area, location, and city, in which the schools and madrasahs are based. Classroom conditions and teaching methods vary considerably. Therefore, although it is possible to assume that an average student after certain years of study, acquire knowledge of basic structures of English, however, it would be a misconception to assume that an average student across different villages, towns, and cities equally knows the structures of the language.

Social stratification shows that people acquire varying status in the society; they belong to many social groups; and they perform a large variety of social roles. People's social identity can be defined in terms of various factors such as social class, caste, colour, and family lineage, rank, occupation, genders, age groups, material possession, education etc. Linguistic correlates of all these factors can be found at all levels.

One of the chief forms of sociolinguitic identity derives from the way in which people are organised into higherarchically ordered social groups or classes. Classes are aggregates of people with similar social or economic characteristics. In Bangladesh the main variables in social stratification can be described in terms of urban versus rural; rich versus poor (economically advantaged versus disadvantaged groups); male versus female etc. Proficiency levels in English vary across these variables. Besides, different types of schools (for accommodating different classes of people), different types of teaching materials, teachers proficiency levels have impact upon the students' proficiency in English. This chapter attempts a discussion on how social differences relate to the proficiency levels of the students across schools and madrasahs in Bangladesh.

2.2 Social strata and students' proficiency levels

2.2.1 Urban versus rural

Students from urban areas show better proficiency in comparison with the students from the rural areas. Most of the urban students watch cable televisions; have easy access to cyber café; a good number of them read English newspapers. Some urban parents subscribe for English dailies. That is, the urban students have the opportunity to use English outside their classroom. In some urban schools computer education has been made compulsory from very early years of schooling. This makes the students learn and use English words and vocabulary items related to information communication technology (ICT). Their proficiency level is, therefore, much higher than that of the rural students. This is worth noting in different competitive examinations like admission tests in different universities and institutions, job interviews etc. In all cases the urban competitors especially, those from the metropolis do better than others.

2.2.2 Rich versus poor

Usually economically advantaged students do better than economically disadvantaged students across the towns and villages. However, a few exceptions may be noticed in all areas. But observation shows that upper class people are more proficient in English than the middle and lower class people, and the middle class people are more proficient than the lower class.

Another important aspect of family lineage is education. Especially the ones, whose parents are educated, have opportunity to use English in their family environment. This helps them to develop their proficiency in English and they do better than those whose parents are not educated.

With the introduction of compulsory primary education for all, many children from economically disadvantaged family have now got their names enrolled in primary schools and madrasahs, but this gives them just a nominal studentship. They acquire hardly any proficiency in English. And many of them do not continue their studies up to the secondary level.

The above discussion, by no means, means that all poor students will do worse than the rich students. The top-bottom polarisation of students' merits and their English proficiency does not parallel the top-bottom polarisation of people in terms of their socio-economic status.

However, economically advantaged parents tend to send their children to prestigious schools- as mentioned earlier, to English medium schools in some cases. This gives them a chance to use English to a greater extent and achieve a better proficiency in English. Furthermore, families whose children have the opportunity to operate cable television, use Internet and read English newspapers are likely to be more proficient than others.

2.2.3 Male versus female

In general, male students show better proficiency than their female classmates do. But it can be said that the girls from the urban areas in most cases do better than the boys from the rural areas with some exceptions being noticed. However, in higher-class families the proficiency level difference between male and female students becomes minimal. With the introduction of free education and stipend for female students of government and non-government schools and madrasahs up to class 12, a large number of female students have enrolled their name in schools. However, many of them cannot take studies seriously; their proficiency in English like in any other subjects is not up to the level of other students.

Despite the above cases, there are many girl students who are more proficient in English than the boy students. These girls do better than some boys in other subjects as well. That is sex as social variable has very little influence on English language proficiency of the school going students (secondary level students). However, many families do not take care of educating their girl children to the same extent as they do of educating their boy children. There are various reasons behind this; lack of social security, earlier marriage of girls and men being the only earning members of most families are some of these. In most families, women are hardly seen to be engaged in money incoming jobs. This is why they do not think of being proficient in English, which could ensure them getting good jobs. For the same reason very few girl students endeavour for higher education. These definitely have impact upon women education and upon their English language education.

2.3 Different types of school and different levels of proficiency

All schools and madrasahs do not have equal opportunity. Some urban schools, for example, include computer education as a compulsory subject, appoint well to do teaching staff for educating their students in a proper way. In a few urban schools only there are modern facilities available for language teaching. Most of the village schools do not have an English subject teacher. Teachers of other subjects in many schools teach English.

Moreover, different types of textbooks are adopted in different schools. Although all schools across the country under five general education boards have to teach their students the book English For Today published by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) as the main textbook, the teaching methods differ from school to school considerably. It can be mentioned here that for the classes six through twelve the national curriculum and textbook board published two sets of books for all curricular subjects except English and Bengali English and Bengali versions. In a few urban schools students have the two options to choose either set. In general, those who take English version show better proficiency than those who take Bengali version do. Besides, there are some English medium schools, which do not follow the curriculum of the NCTB. The majority of these schools claim to follow British curricula and their students prepare to sit for GEC O' and A' levels examinations. Some other schools, however, follow American curricula while some others follow others. Students of these English medium schools though are better in English their condition in Bengali is equally worse.

Bengali is the language of everyday communication throughout the country. But people who have the opportunity to use cable televisions and Internet are seen to switch over to English very frequently while speaking in Bengali. This is more common in urban areas than rural areas, in higher class than middle and lower classes. The opposite happens while the madrasah students especially the 'qawmi' madrasah students speak in Bengali. These students tend to switch over to Arabic and Urdu instead. They are, therefore, more proficient in Arabic and Urdu than English.

In above paragraphs, it has been shown that there are three categories of schools/educational institutions in Bangladesh for three classes of people. These are English medium schools, Bengali medium schools and madrasahs. The English schools are mostly very expensive and the madrasahs are cheapest. There is yet another category of schools where most of the middle class parents send their children especially for the early years of schooling. These are generally known as kindergarten schools (KG schools). The economically advantaged (rich) people send their children to English medium schools while the economically disadvantaged (poor) people send their children to madrasahs. The upper middle class people try to send children to English medium schools. However, there are a few Bengali medium schools, which are regarded as prestigious. The middle and upper middle class people in some instances try to get their children admitted in these schools.

2.3.1 Information by and from learners and teachers

In this investigation 300 students 100 from urban schools, 100 from rural schools, 50 students from urban madrasahs and 50 from rural madrasahs have been interviewed. In each area, students were selected randomly from junior secondary (JS) and secondary (S) levels disregarding their merit and place in classes. 100 teachers - 35 from urban schools, 35 from rural schools, 15 from urban madrasahs and 15 from rural madrasahs were also interviewed. Teacher samples were selected from those who teach English in any class from classes 6 to 10 in their institutions. While investigating, this researcher talked with them formally and informally. The formal investigation comprised questionnaires and the student and teacher samples. Informal investigation was carried out through observation and discussion with teachers and head teachers of different institutions. The researcher also talked with other groups of people concerned e.g., guardians and job givers. Discussion with all concerned reveals same kind of impression about English language proficiency across the country.

2.3.1.1 Students' proficiency levels as viewed by students

Students' responses to items 16 and 17 of the students' questionnaire reflect students' proficiency levels as viewed by the students themselves. In response to item 16/a (Do you think that you can cope with your teacher if he/she teaches in English?) most urban students (73 school students out of 100 and 33 madrasah students out of 50) answered in affirmative. From the rural areas also more than half of the students (57 school students out of 100 and 28 madrasah students out of 50) said that they could cope with their teachers if they teaches in English. Here the number of respondents form madrasahs is equally satisfactory as from schools. However, in students' evaluation of their proficiency, urban students marked higher than the rural students marked. The following table shows how students from different backgrounds responded to the question "How do you evaluate your proficiency?" (Item 16/b)

|

Options |

Student samples(300) |

|||

|

Urban school (100) |

Urban madrasah (50) |

Rural school (100) |

Rural madrasah (50) |

|

|

Very good |

None |

none |

None |

None |

|

Good |

34 |

11 |

23 |

8 |

|

Average |

27 |

11 |

20 |

14 |

|

Weak |

12 |

11 |

14 |

6 |

|

Did not respond |

27 |

17 |

43 |

22 |

Table 2.1: Students' proficiency level as viewed by students

Students' responses to item 17 (Evaluate your different skills in English. Tick appropriate boxes) reveal that they are mostly weak in speaking and listening. They are better in writing and reading than in speaking and listening. This is perhaps the result of our long-standing tradition of teaching literary English that excluded any oral interaction in the class. However, their proficiency is not up to the mark in reading and writing as well and the condition is worse in rural areas than urban areas and madrasah students are weaker than school students. The following tables shows how students evaluated their proficiency in different skills:

|

|

Students from urban schools (100) |

Students from urban madrasahs (50) |

Students from rural schools (100) |

Students from rural madrasahs (50) |

||||||||||||

|

|

L |

S |

R |

W |

L |

S |

R |

W |

L |

S |

R |

W |

L |

S |

R |

W |

|

Very good |

12 |

7 |

12 |

8 |

2 |

— |

5 |

5 |

10 |

— |

17 |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Good |

35 |

37 |

40 |

40 |

15 |

17 |

30 |

27 |

35 |

38 |

38 |

31 |

13 |

13 |

19 |

17 |

|

Average |

28 |

31 |

40 |

42 |

23 |

20 |

13 |

14 |

31 |

37 |

41 |

39 |

16 |

9 |

16 |

17 |

|

Weak |

25 |

25 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

13 |

2 |

4 |

24 |

25 |

4 |

25 |

31 |

28 |

15 |

16 |

Table 2.2: Students proficiency in four basic skills as viewed by students

Information furnished in the above tables is not unaffected by such things as the locality where the school/madrasah is situated, learners' age, sex and what type institute it is. Learners have been seen to evaluate their own proficiency in comparison with the other students of their own class, institute and locality. The rural students, for example, are unlikely to compare their performance with urban students and the vice versa. In the same way, the madrasah students are not likely to compare themselves with school students and the vice versa. The researcher's informal observation as well as students' performance in different competitive examinations and admission tests in different institutes reveal that urban students do better than rural ones and school students do better than madrasah students.

2.3.1.2 Students' proficiency levels as viewed by teachers

Teachers' response to items 16, 17, 18 and 19 of the teachers' questionnaire shows how teachers of different institutions across villages, towns and cities view their students' proficiency levels in English. In response to the question "Are they (your students) able to follow your class if conducted in English?" (Item 16), very few teachers of the rural areas answered in affirmative. Teachers from very well reputed schools of the urban areas answered in affirmative. Other urban teachers mostly ticked 'yes'. However, some of their urban colleagues confused and so, did not answered the question. Their confusion was obvious in the informal discussion with these teachers. So far as rural teachers are concerned the responses are mostly negative. Only a few teachers from very well reputed schools answered in positive. In this regard madrasah teachers were found responding mostly in negative. However, many madrasah teachers said they did a part time job in the madrasahs. These teachers are mostly full time teachers of different schools and colleges. The following table projects their answers:

|

|

Teacher samples |

Number of teachers who answered ‘yes’ |

|

Urban schools |

35 |

28 |

|

Rural schools |

35 |

11 |

|

Urban madrasahs |

15 |

5 |

|

Rural madrasahs |

15 |

Nil |

Table 2.3: Students proficiency levels as viewed by teachers

Teachers' answers to item 17 (Do they raise questions in English?) and item 18 of the teachers' questionnaire, projects the same type of information as furnished in above table. However, in response to item 19 (Do your students write creatively?), very few teachers answered in affirmative - only 15 urban school teachers and 2 urban madrasah teachers. No teachers from the rural areas answered in affirmative to this question.

2.3.2 Extent of students' use of English

2.3.2.1 Extent of students' use of English as viewed by the students

The choice of a methodology in the language classroom is to a greater extent determined by to what extent the language is used in everyday life or outside classroom. In a monolingual language situation like Bangladesh, students have very little scope to use English in everyday life. However, in the present age of globalisation, different milieus of information communication technology have purveyed some students with access to internet, satellite television, mobile phone etc. This class of people have an opportunity to use English in occasions. This opportunity is not plainly distributed to all population of the country across villages and towns. Rather there is always differences between the urban and rural areas and in the same way between rich and poor people. Students from urban areas are seen to go to cyber cafes, watch cable television while rural students lack these facilities. Watching television still has been strictly prohibited for some madrasahs students. Even reading newspapers and magazines is discouraged in some madrasahs.

It has been observed that most urban school students (especially, those from the metropolis) read English newspapers or magazines, watch cable televisions, go to cyber cafes. These give them some chances to use English. Rural students are hardly seen to do these. The first category of the students frequently switch over to English while speaking with others though in Bengali. This type of code switching is also noticeable in the language of rural school students to a lesser extent. Madrasahs students, on the other hand, frequently switch over to Arabic or Urdu.

Items 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 of the students' questionnaire reflect to what extent students use English inside classroom and item 10 reflects to what extent they use English outside the classroom that is, for real communication.

In response to item 5 (Which language(s) do you mostly use in English classes?) and item 6 (Which language(s) does your teacher mostly use in English classes?), almost all the students ticked the option English and Bengali. However, their rating in response to item 7 (How often classroom discussion is conducted in English in English classes?) and item 9 (How often do you participate in group or pair work/discussion?), differs across towns and villages. Although most of the students of all the institutes ticked the option sometimes, a good number of urban students ticked always in item 7 and always and very often in item 9. Their responses to items 7 and 9 are illustrated in table 2.4 and 2.5 respectively.

Table 2.4: Extent of use of English in classroom discussion as viewed by students

|

Options |

Student samples(300) |

|||

|

Urban |

Rural |

|||

|

School (100) |

Madrasah (50) |

School (100) |

Madrasah (50) |

|

|

Always |

13 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Sometimes |

81 |

40 |

86 |

37 |

|

Rarely |

6 |

8 |

10 |

13 |

|

Never |

— |

— |

4 |

— |

|

Did not answer |

— |

2 |

— |

— |

In response to item 8 (Do you practise the four skills in your English class?), all the students answered in affirmative for the reading and writing skills. In respect to two auditory vocal skills, i.e., listening and speaking, most urban students and a few rural students answered in affirmative. The following table projects their answers.

Table 2.5: Extent of students' participation is pair/group work/discussion as viewed by students

|

Options |

Student samples(300) |

|||

|

Urban |

Rural |

|||

|

School (100) |

Madrasah (50) |

School (100) |

Madrasah (50) |

|

|

Always |

11 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Very often |

11 |

|

8 |

7 |

|

Sometimes |

72 |

40 |

78 |

30 |

|

Rarely |

6 |

8 |

8 |

10 |

|

Never |

— |

— |

4 |

3 |

|

Did not answer |

— |

2 |

— |

— |

Table 2.6: Extent of practising four skills as viewed by students

As projected in the above table, emphasis is given on reading and writing skills in the English classroom. Listening and speaking skills are not practised to same extent as the other two skills are.

Responses to item 18 project students' real life use of English language. The following table shows how different groups of students responded to item 18 (Which of the following things do you do?) of the students' questionnaire: (Number mentioned against each item indicates how many students ticked the item.)

|

Use of English |

Student samples |

|||

|

School |

Madrasah |

|||

|

Urban (100) |

Rural (100) |

Urban (50) |

Rural (50) |

|

|

Use English in family environment |

22 |

13 |

10 |

6 |

|

Listen to TV news in English and see English TV programmes |

53 |

34 |

14 |

6 |

|

Speak in English with teachers and other students in the English class (sometimes) |

59 |

41 |

19 |

14 |

|

Read English newspapers |

37 |

7 |

5 |

Nil |

|

Read English books |

37 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

|

Write letters in English |

3 |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

Table 2.7: Students' use of English in real life as viewed by students

Information provided in the above table reveals the extent of use of English by students from different backgrounds. The table projects that the urban students use English to a greater extent than the rural ones and school students use English to a greater extent than madrasah students.

2.3.2.2 Extent of students' use of English as viewed by teachers

In teachers' evaluation, students use English in their practical life to a lesser extent than the extent viewed by the students themselves. Teachers' responses to item 20 of the teachers' questionnaire (How many of your students do the following things?) reflect their evaluation. Most of the teachers ticked the option 'a few' for most of the activities. The following table projects their responses:

|

How many students |

Teacher samples(100) |

|||||||||

|

Urban (50) |

Rural (50) |

|||||||||

|

All |

many |

Some |

a few |

none |

all |

many |

some |

a few |

None |

|

|

Use English in family environment |

Nil |

nil |

Nil |

36 |

14 |

nil |

nil |

|

30 |

20 |

|

Listen to TV news, see English TV programmes |

Nil |

nil |

26 |

23 |

1 |

nil |

nil |

5 |

45 |

nil |

|

Speak in English with teachers and other students in the English class (sometimes) |

Nil |

nil |

25 |

25 |

nil |

nil |

nil |

6 |

44 |

nil |

|

Read English newspapers |

Nil |

nil |

22 |

25 |

3 |

nil |

nil |

nil |

23 |

27 |

|

Read English books |

Nil |

nil |

12 |

32 |

6 |

nil |

nil |

|

24 |

26 |

|

Write letters in English |

Nil |

nil |

Nil |

16 |

34 |

nil |

nil |

10 |

9 |

31 |

Table 2.8: Extent of students' use of English as viewed by teachers

In the above table number of respondent teachers is mentioned in cardinal numbers and number of students who the teachers think perform the activities is written in the first column in scale amount words.

The table projects that most of urban (36) and rural (30) teachers say that a few of their students use English in family environment and some teachers (14 urban and 20 rural teachers) say that none of their students use English in family environment.

26 urban teachers and only 5 rural teachers say that some of their students listen to TV English news and see English programmes on televisions. 23 urban and 45 rural teachers say that a few students do these activities. However, 1 urban teachers says none of his students do these.

Half of the urban teacher samples (25) find their students sometimes speaking in English in the class and the other half find a few of their students doing that. On the other hand, only 6 rural teachers say that some of their students speak in English in the class and 44 teachers say "a few".

Most teachers say that a few students read English newspapers or English books. Most teachers think that none of their students write letters in English. 25 teachers (16 urban and 9 rural) think that a few students do this. However, 10 teachers from rural areas find some students writing letters in English.

In the above projection, teachers' responses are, of coarse, subjective. However, despite its subjectivity, it gives an overall picture of the students' extent of use of English in the daily life.

Observation amid different schools and institutions reveals that according to most teachers' evaluation, a very few urban students of junior secondary level can write a sentence of their own let alone a letter or paragraph.

So far as madrasah teachers responded, only a few madrasah students of the urban areas take the English subject seriously and can write a sentence of their own. The condition goes worse in higher classes. As a cause of this ill condition, the teachers mentioned the infrastructure of their institutions as unsuitable for carrying out effective teaching. Again a good number of students, who are very serious about their career leave madrasah and join schools and colleges in different stages of their study. The students who still remain with madrasah education, in most cases, take study as part time. Some do jobs as imams or muajjins in local mosques and some teach the children how to recite the Quran in village maqtabs.

2.4 Different types of teaching materials

In all the schools i.e., institutes of general education subsystem, the book English for Today is compulsory and in examinations, a seen comprehension passage is set from these textbooks. And there is an unseen comprehension; for this, students follow any of the books published by different publishers and approved by the NCTB (National Curriculum and Textbook Board). Again, these publishers also publish notebooks and guidebooks. However, all these books aim to help the students to do better in the examinations rather than to help them understand the textbooks. The nomenclature of some notebooks, e.g., Kamyab English, Touch and Pass, Sure Success etc. reflects how the publishers and writers of these books try to attract the student customers.

The Madrasah Education Board does not publish any English book for any classes. It approves books of different publishers and includes their names in its Curriculum and Syllabus report. As the madrasah board follow a traditional syllabus, these books are also written in a traditional manner. In fact, Madrasah Education Board does not give any syllabus specification for any class in terms of learning outcomes. Rather a list of prose and poetry and some explicit grammatical items are prescribed as syllabus for class 9 and 10. From classes 6 to 8, the condition is bad to worse. Here, in the name of syllabus, only the tittles of some books are listed as options, from which madrasahs can choose any.

Again, many madrasah students do not care about buying textbooks, rather they run for buying only guidebooks just weeks or days before the final examinations. As many madrasah students take their studies as part time, their irregular attendance help them a little with original textbooks.

In the national curriculum report, supplementary grammar books and English rapid readers have been suggestive for different classes. However, only a few urban schools include rapid readers in their syllabuses. And supplementary grammar books mean in most cases a book of traditional grammar, which include in it traditional definitions of grammar items, sample translation and so called model composition on stereotyped topics like a village doctor, a postman, golden fibre of Bangladesh and so on. There are a few urban schools, however, that include in their syllabuses books like Oxford Practice Grammar (by John Eastwood) or English Grammar in Use (by Raymond Murphy).

2.5 Teachers' proficiency levels

Teachers' proficiency levels vary from urban to rural areas considerably. The urban schools usually recruit qualified teachers, while the rural schools lack sufficient number of English teachers. In many rural schools, teachers of other subjects teach English. In many urban schools English teachers are graduates of English from Universities. Although these teachers are, in most cases, English literature graduates, they do better than those who are graduated from other subjects. Again, most of the teachers of reputed urban schools have pre-service or in-service training in English Language Teaching (ELT). Of coarse, a good number of English teachers across villages, towns and cities have a B.Ed. degree with English as a main subject. But in most cases their proficiency in English in not satisfactory. Most of the teachers are not familiar with communicative approach to language teaching. They dot not know what process oriented and product oriented syllabuses are.

Most of them (especially, those from rural areas) cannot write a piece of text (a letter or paragraph) of their own. They hardly listen to any English TV programme. They rarely use English to communicate with their students in English classes. They rarely read any English newspaper or any book written in English. While teaching, these teachers strive more on how far they can ensure that their students can cut good marks in their examinations. How to make teaching and learning more effective is hardly a matter of concern of these teachers. In most of the rural schools and many urban schools, the common picture is that their teachers are not fluent in listening, speaking, reading and writing. They just know the grammar of English and how to teach this grammar. The condition in madrasahs is bad to worse. As most of the madrasahs run with subscriptions or donations from the people and always lack sufficient fund, they cannot appoint full time English teachers. Teachers of schools and colleges teach in many madrasahs part time - two or three days a week.

In the institutions where there are English subject teachers, these teachers are not always graduates of English language. Most teachers have a B.A. degree with English as a compulsory subject. Some teachers, however, took elective English subject of three hundred marks (in three papers) in their B.A level. Of these three papers, only one paper is of English language (English grammar, translation and composition writing) and the rest two are of literature.

There are few teachers graduated in English Language, or Applied Linguistics and English Language Teaching (ELT) or Linguistics. However, it is a matter of concern that literary experts select our English teachers. These experts are not always familiar with the modern development in applied linguistics and language teaching. As a result, many of them choose English literature graduates to teach English whereas those graduated from the department of Linguistics and English language should be given preference. As most of the teachers have little knowledge of linguistics and language teaching, they cannot cope with the new development in this field. As a result, their methodology of teaching differs from what is intended in the new curriculum. As Abdus Selim and Tasneem S. Mahboob (2001) said, while the very aim behind introducing new syllabus of English was to teach English as a language, giving special attention to idiomatic and phonetic aspects of the language the whole idea gets lost in the wilderness as the teachers have poor knowledge of phonetics. They also ignore the comprehension aspect, which is closely connected with the functional side of the language, as they bank heavily on grammar-translation method.

2.5.1 Teachers' proficiency level as viewed by teachers

Teachers' responses to item 3 reflect how they evaluate their proficiency in English. As projected in the following table, most of the teachers (62 out of 100) across villages and towns ticked the option 'good'. The second option (ticked by 33 teachers) is the option 'medium'. Teachers' responses to this question do not show any difference in their proficiency levels between rural and urban areas or between schoolteachers and madrasah teachers. However, a few urban schoolteachers preferred the option 'very good', which no rural teachers and no madrasah teachers ticked.

Table 2.9: Teachers' proficiency levels as perceived by teachers

(Note: *One

urban teacher ticked two options.)

|

Skills |

Teacher samples (100) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Urban school (35) |

Rural school (35) |

Urban madrasah (15) |

Rural madrasah (15) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Very good |

Good

|

Medium |

Weak |

Very weak |

Very good |

Good

|

Medium |

Weak |

Very weak |

Very good |

Good

|

Medium |

Weak |

Very weak |

Very good |

Good

|

Medium |

Weak |

Very weak |

|

|

Listening |

9 |

5* |

18* |

4 |

|

|

8 |

27 |

|

|

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

5 |

10 |

|

|

|

Speaking |

9 |

5 |

14 |

7 |

|

|

5 |

23 |

7 |

|

|

|

11 |

4 |

|

|

4 |

10 |

|

1 |

|

Reading |

31 |

4 |

|

|

|

32 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

11 |

4 |

|

|

2 |

10 |

3 |

|

|

Writing |

31 |

4 |

|

|

|

30 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

11 |

3 |

1 |

|

2 |

10 |

3 |

|

|

Although it is the case that many urban English teachers are university graduates of English and many rural English teachers are actually teachers of others subjects like mathematics or science and many madrasah English teachers teach part time, the above table does not project any significant difference between proficiency levels of the teachers from different backgrounds. This does not mean that the urban and the rural teachers are more or less equally proficient in English. Rather our teacher samples from different backgrounds compared their skills and proficiency with those of their colleagues in the same institutes or same environments. They, in most cases, failed to address and question their own state in comparison with that of others in different environments.

So far as teaching skill is concerned almost half of the teachers evaluated their state (in response to item 4 of the teachers' questionnaire) as average and the other half as good. There is significant difference between urban and rural teachers' evaluations. The same reason is found behind this gross; that is, not many teachers compared their own skills with those of others in a different environment. However, their responses to item 5 reflect how far they are acquainted with the present trends in language teaching. Only a few teachers (15 from urban schools and 7 from rural schools) were found familiar with product and process oriented syllabuses, although almost all the teachers from both areas (48 urban and 49 rural) ticked 'yes' for the options communicative language teaching (CLT) and grammar translation method (GTM) (in response to item 5). 20 urban teachers (18 from schools and 2 from madrasahs) and only 7 rural teachers (all of them are schoolteachers) said that they were familiar with 'direct method'.

2.5.2 Extent of use of English

Not many teachers use English in their English classes. Only a few urban teachers occasionally use English outside the classroom. They subscribe, or at least read English newspapers. However, no one was found among the teacher samples who read English books for pleasure. Teachers' responses to item 6 and 12 of the teachers' questionnaire reflect the extent of use of English of the teacher community. Responses to item 6 reveal how often the teachers use English. The following table shows how they responded:

|

|

Number of teachers who answered ‘yes’ |

|||

|

School |

Madrasah |

|||

|

Urban (35) |

Rural (35) |

Urban (15) |

Rural (15) |

|

|

Listen to radio and TV news and see English TV programs |

25 |

22 |

5 |

5 |

|

Speak in English with colleagues and others |

27 |

22 |

9 |

5 |

|

Read English books for pleasure |

5 |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Read English newspapers |

24 |

14 |

5 |

Nil |

Table 2.10: Extent of teachers' use of English as perceived by teachers

The information furnished in above table projects the extent of use of English of the teachers of schools and madrasahs across villages and towns.

Item 12 of the teachers' questionnaire projects how often teachers use English in English classes. In response to the question "Which language(s) do you use for classroom instructions?" all the teachers ticked the option 'English and Bengali'. However, while giving a rating for English and Bengali, none of the rural teachers gave more than 50% rating for English, while most of them (37 out of 50) gave a rating for English that was below 40 percent. On the other hand, only 10% (5 out of 50) urban teachers' rating for English was below 50%. 20% (10 out of 50) urban teachers gave a rating for English that was 65% or above 65%. Two urban teachers wrote that they used 90% English in English classes.

2.5.3 Teacher training

So far as teacher training is concerned, there is arrangement for training teachers of all levels. Primary teachers are trained in Primary Training Institutes (PTIs). There are 49 PTIs in the country. They produce about 100 teachers each year. Although primary teachers are expected to teach English as a compulsory subject from class one, there is no ELT provision in PTIs.