ABSTRACT

The paper explores some of the morphological aspects in the perspective of non-concatenative morphology. The notion has come forward to explain some of the morphemic alternations in the light of Lexical phonology. Cross-linguistic examinations reveal that the length of a vowel presents grammatical information, within the morpheme. In Hindi concatenative as well as non-concatenative morphological processes, are observed in causative verbal sets, reduplicated nominals, diminutive forms etc. An attempt is made to elaborate some processes that are conditioned by phonological processes. In this regard, a lexical phonological model is developed which suggests that level ordering allow some phonological rules to precede some morphological ones. The multi layered model suggests that non-concatenative morphological processes are prior to concatenation of morphemic elements in Hindi.

1. INTRODUCTION

Various scholars namely, Kiparsky 1985, Mohanan 1990, Kaisse & Shaw 1985 recognize phonological rules in a grammar into two modules -Lexical and Post Lexical. Lexical rules apply within words and post lexical rules apply across word boundary. Lexical rules interact with phonology at different strata and are cyclic. On the other hand, post lexical rules apply after morphological and syntactic rules and are non-cyclic. It is possible to have exceptions in lexical rules but post lexical rules are exception less.

Cross-linguistic examinations reveal that there are languages in which grammatical information is presented by the length of a vowel, within the morpheme. In New Zealand Maori (as reported in McCarthy:1992) Nouns denote plurality by lengthening the vowel of the first syllable. For instance,

Singular: tangata 'person' wahine 'woman'

Plural: taangata 'persons' waahine 'women'McCarthy states that the theory of non-concatanative morphology owes a great deal to Harris' notion of long components. (1941; 1951). This includes reduplication, in fixation, morphologically govern ablaut and superaffixation. He further considers it a prosodic theory in the sense that it uses the devices of autosegmental phonology. According to him, the non-concatenative morphological system prevails in most of the Semitic languages.

The morphology of Semitic languages is pervaded by a variety of morphological alternations within the stem. In Arabic, for instance, the forms are morphologically related to one another.The following examples are illustrated in McCarthy (1981:374), these examples show a systematic relationship and Non-concatenative morphological processes.

a. kataba 'he wrote'

b. kattaba 'he caused to write'

c. kaataba 'he corresponded'

d. takaatabuu 'they kept up a correspondence'

e. ktataba 'he wrote, copied'

f. kitaabun 'book [nom.]

g. kuttaabun 'koran school' [nom.]

h. kitaabatun 'act of writing' [nom.]

i. maktabun 'office'Lexical phonology looks at these word items as the central component of the grammar that contain idiosyncratic properties of words and morphemes and also regular word formation and phonological rules. It is assumed that word formation rules of the morphology are paired with phonological rules grouped together at various levels. The output of each morphological rule is cycled through the phonological rules of that level. In turn, phonology of that level triggers the next level of morphological rules, paring with phonological rules of that level. In this sense, the rules of morphology and phonology are cyclical. They are made to apply in a cycle, first to the root then out ward to the affixes nearest to the root and then to the outer layer of the affixes. Thus, the "lexical rules" apply within the words whereas "post lexical" rules apply across the boundary. This is illustrated in the following model (McCarthy: 1992) that suggests level ordering.

2. LEXICAL MODEL FOR HINDI

Considering vowel alternation occurs before 'level 1' morphology in Hindi, above-mentioned strata are modified accommodating non-concatenative morphological process on "level 0". The alternation on this level, in turn, triggers the other morphological concatenations. The model is as follows:

Hindi consists of vocables belonging to different strata. The initial classification is between 'native' and 'borrowed' as they yield different derivational outputs. However the borrowed vocabulary can be further classified into 'tatsama' and 'tadbhava'. Tatsama words are the Sanskrit words and borrowed in Hindi as they are without any change. 'tadbhava' are the borrowed form of Sanskrit but changed and merged with the native words yet 'look alike' Sanskrit words. It has been observed that native vocabulary follow somewhat different morpho-phonemic rules. Thus unlike {raajaa}, a native word {laDakaa} has different plural and oblique forms.

Nouns inflect for gender, number and oblique form. The order for the suffixes is Noun stem + gender + oblique case. As our proposed model suggests that the non-concatenative alternation occurs on level 0, prior to level 1 morphology. Following figure illustrates the organization:

Since non-concatenative morphological process triggers a systematic concatenative morphological process, morphological levels are assigned as follows: (Bharati: 1988)

Level 1 - the level of pre-fixation and primary derivation;

Level 2 - the level of compounding;

Level 3 - the level of inflection and reduplicative compoundingConsider the above organisation in the following example :

level 0: [vadhuu] n > *[vadhu] ‘bride’

v a dh uu > v a dh u

c v c vv > c v c v

level 1:+ inflection: [ [ vadhu ]n [e~] ]pl. > [vadhue~]n

[ [ vadhu ]n [o~] ]pl. obl. > [vadhuo~]n

level 2:compuonding: [ [ vadhu]n [paksh]]n > [vadhupaksh]n

level 3:# derivation: [ [ vadhupaksh]n [iiya]] adj > [vadhupakshiiya}adj

3. NON-CONCATENATIVE PROCESS IN THE FORMATION OF CAUSATIVE VERB FORMS

In Hindi, causativization of a verb stem involves the alternation between short and long vowel as well as the concatenation of the affixes. The formation of the verbal sets contains phonological and semantic information. Morphologically they are partially similar. The construction of the causal verb may be seen at two levels: viz. 'Productive' and 'Lexical'. Morphologically regular forms may be seen at the productive level and morphologically irregular forms may be seen at the lexical level. Syntactically causative forms reveal direct and indirect causation. Kellog [1887:252] notes this distinction as 'primitive', 'causal' and 'second causal' verb. "From every verb in Hindi, may be derived a causal and a second causal verb. The first causal expresses 'immediate causation' and the second causal 'indirect causation' of the act or the state of the primitive".

Saksena [1982] considers a transitive verb form to be the 'base' for all the formations. She argues that the transitive verb form, having a long vowel, should be considered as 'base' form. If intransitive verb form is considered as basic, the morphological generalizations are not possible, because causativization by vowel lengthening is syntactically restricted. Moreover phonologically it is ambiguous to know whether short vowel will alternate with long /ii/, /uu/ or with long /E/ and /O/. While via reduction rule long /E/ and /O/ alters with /i/ and /u/ respectively. Pray [1976] considers that the majority of verb stems are 'tadbhava' forms. Non-tadbhava forms are mostly borrowed as nouns or adjectives, not as verbs. Hence, the alternation of tense and lax vowels characterizes many kinds of phonological forms in addition to a sequence, which constitute a stem but not the entire word [Pray: 1976: 96].

The discussion endorses our proposed 'Level 0' of non-concatenative morphology. These rules are cyclic and hence they apply to one layer at a time. The output of non-concatenative 'level 0' can undergo the rule at 'level 1' It can not interact with 'level 2' phonological rule and vice versa. Strict cyclicty also ensures that phonological rules only have access to morphological information at the same level. In this sense level ordering reflects 'degree of productivity'. Causative formation on the Hindi verbs is a systematic process, although, it may be noted that the causativization is terminated at the 'level 1' morphology. Consider the following data:

Level 0 [chiil] vt > [chil] vi ‘to peel’

Level 1 [[chil]aa]] c [[chil]vaa]] c ‘to cause to peel’

L 0 [naac] vi > [nac] ‘to dance’

L 1 [[nac]aa]]c > [[nac]vaa]] c ‘to cause to dance’

L 0 [TaTol] > [TaTul] ‘to feel’

L 1 [[TaTul]vaa]] c ‘to cause to feel’

L0 [de] > [di] ‘to give’

L1 [[di]laa]] [[dil]vaa]] ‘to cause to give.

L0 [kuud] vt > [kud] ‘to jump’

L1 [[kud]aa]] vt ‘to cause to jump’ (direct)

[[kud]vaa]] vt ‘to cause to jump’ ( indirect)

L0 [umeTh] vt > [umith] ‘to twist’

L1 [[umiTh]vaa]] vt ‘to cause to twist’ (indirect)

In all above mentioned instances vowel reduction renders the stem for the causative formation.

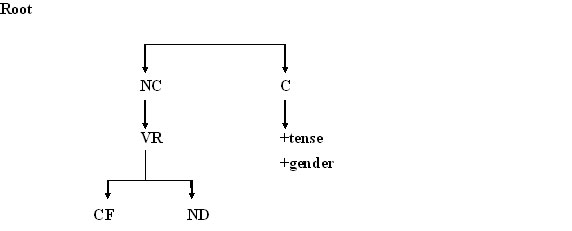

It is interesting to note that the morphology of verbs interact with the morphology of nouns. For instance, a homonymous word, which is either a noun or a verb or both, is derived into a stem through non-concatenative process on the 'level 0' followed by the concatenations for inflection and derivation of the word on the higher level. The following schema illustrates as under:

In the above schema NC stands for 'non-concatenative' morphological processes, C stands for'concatenative' morphological processes, VR stands for 'vowel reduction', CF stands for 'causative fornmations' and ND stands for the 'nominal derivations.'

Examples:

{khel} n 'a game'

{khel} v 'to play'

{khel}> *{khil} > {khilvaanaa} 'to cause to play'; {khilOna} 'toy', (khilvaad'}, {khilaad'ii} 'player'4. NON-CONCATENATIVE PROCESS IN THE FORMATION OF DIMINUTIVE OF NOMINATIVE FORMS

Another similar yet systematic process of non-concatenative morphology can be observed in the formation of diminutive forms. Consider the following examples:

lotaa 'tumbler' > lutiya 'small tumbler'

khaat 'bed' > khatiya 'small bed'These instances show systematic vowel alternation at 'level 0' before /-iya/ affixation. /O/ alters with /u/. Diminutives are also formed with gender alternation. For instance, [hathODaa] 'hammer-big masculine' > [hathODii] 'hammer- small feminine'

In this case gender information is revealed by vowel alternation at the 'level 0' only.

Following nominative formations also follow 'level 0' morphology via reduction rule before concatenation of the affixes.

lohaa 'Iron' > luhaar 'black smith'

sonaa 'gold' > sunaar 'gold smith'5. NON-CONCATENATIVE PROCESS IN COMPOUNDING

Consider the process in the following examples:

ghoDa + dOD > ghUD dOD 'horse race'

L 0: ghoDaa > ghuD

L 1: ghuD dOD

raajaa + vaaDaa > rajvaaDaa 'royal dwelling'

L 0: raajaa > raj

L 1: raj vaaDaa

paanii + chakkii > panchakkii 'flour mill, run by hydro energy'

L 0: paanii > pan

L 1: panchakkii

paanii + vaaDii > panvaaDii 'beetle vendor'

L 0: paanii > pan

L 1: panvaaDiiNon-concatenative process is also seen in echo words formation. These are formed by 'vowel alternation' in echo word. The vowel of the echo word is changed to /uu/ if the vowel of the original word is /aa/. The echo word takes the vowel /aa/ if the vowel of the main word is any vowel other than /aa/ (Singh 1971).

{paaTpuuT} 'to level', {chaaT chuuT} 'to lick', {khii~c khaa~c} 'to pull', {mod' maad'} 'to fold'.Another interesting set of the 'echo- word' is formed by the affixation of a segment, after deleting the initial segment of the main word. (Singh 1971) This seems to be the only morphological process where the word formation is done by deletion of initial segment rather than the addition or modification.

{saamnaa} 'encounter' > {aamnaa saamnaa}, {pass} 'near' > {aas pass}, (pad'os} 'neighbourhood' > {ad'os pad'os}, {bagal} 'side' >{agal bagal}, {bartan} 'utensils' > {artan bartan}.This may be observed from above mentioned examples that vowel alteration is a systematic process.

6. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

The paper discussed a few aspects of non-concatenative and concatenative morphology of Hindi. It is envisaged that our suggested lexical model will have its applicability in the field of computational linguistics. Moreover, a non-native speaker of Hindi might find this useful since non-concatenative process takes place before most of the concatenations in Hindi.

REFERENCES

Bharati, S. (1988). Some Aspects of Hindi Morphology. Ph. D. Thesis, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Kaisse and Shaw (1985). ON THE THEORY OF LEXICAL PHONOLOGY. Phonology Year Book 2:1-30.

Kellog, S. H. (1965). A Grammar of Hindi Language. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

McCarthy, J. J (1981). A Prosodic Theory of Non-concatenative Morphology. Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 12 no.3 : 373-417.

McCarthy, A. C. (1992). Current Morphology. Routledge , New York.

Mohanan, K. P.(1990). The Theory of Lexical Phonology. D. Reidel Publishing Co., Netherlands.

Pandey, P. K. (1992) Phonetic versus Phonological Rules: Explaining an Ordering Paradox in Lexical Phonology, in Sound Patterns for Phoneticians,(eds) T. Balasubramanian, and V. Prakasham, T. R. Publications, Chennai. 1992.

Pray, B.R. (1970). Topics in Hindi Urdu Grammar, Research Monograph Series No. 1, University of California.

Prasad, K. (ed.) 1956. Brihat Hindi Kosh, Gyan Mandal Ltd., Varanasi.

Saksena, A. (1982). Topics in the Analysis of Causative with an Account of Hindi Paradigms. University College Press, London.

Singh, A. B. (1971). On Echo Words in Hindi. Indian Linguistics, Katre Felicitation Vol.30, Deccan College, Poona.