AN APPEAL FOR SUPPORT

- We are in need of support to meet expenses relating to some new and essential software, formatting of articles and books, maintaining and running the journal through hosting, correrspondences, etc. If you wish to support this voluntary effort, please send your contributions to

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road Suite C

Bloomington

MN 55438, USA.

Also please use the AMAZON link to buy your books. Even the smallest contribution will go a long way in supporting this journal. Thank you. Thirumalai, Editor.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- COMMUNICATION VIA GESTURE: Indian Contexts

- CIEFL Occasional Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 10

- Language, Thought and Disorder

Some Classic Positions by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - English in India: Loyalty and Attitudes by

Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education by

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI AND MALAYALAM by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D.

- LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS IN TAMIL by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D.

- An Introduction to TESOL: Methods of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Transformation of Natural Language into Indexing Language: Kannada - A Case Study by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D.

- How to Learn Another Language? by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Verbal Communication with CP Children by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D. and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Bringing Order to Linguistic Diversity - Language Planning in the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- Lord Macaulay and His Minute on Indian Education

- In Defense of Indian Vernaculars Against Lord Macaulay's Minute By A Contemporary of Lord Macaulay

- Languages of India, Census of India 1991

- The Constitution of India: Provisions Relating to Languages

- The Official Languages Act, 1963 (As Amended 1967)

- Mother Tongues of India, According to 1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES FROM MARCH, 2001 - NOVEMBER 2003

- INDEX OF AUTHORS AND THEIR ARTICLES FROM MARCH, 2001 - NOVEMBER 2003

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org or send your floppy disk (preferably in Microsoft Word) by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road #320

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA. - Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2004

M. S. Thirumalai

STRANGERS IN THEIR OWN LAND!

Campbell's Defense of Indian Vernaculars Against Lord Macaulay's Minute

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. and B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D.

1. REV. WILLIAM CAMPBELL

William Campbell was a missionary in India for over twelve years. Even after his return to Britain, he continued to evince interest in India, and devoted his life for a better understanding of the problems of India among the people in Britain. As a missionary, he dedicated his life for the spread of the Gospel of Jesus Christ among the people of India, especially among the Hindus. His zeal for India's progress took him in a route different from that followed by Lord Macaulay and others, who succeeded in introducing English as the dominant language of education and also of administration and public affairs. The Minute of Lord Macaulay was recorded in the year 1835. (See Language in India, April 2003.) William Campbell was a contemporary to all the leaders, who either supported or opposed the introduction of English as the language of education, administration, and public affairs.

William Campbell wrote a lengthy book of nearly 600 pages to record the current happenings in India. But, as a Christian missionary, his major focus was on the spread of Christianity in India, with the conviction that India would progress materially, spiritually, ethically, and morally, only if people in large numbers accept Jesus Christ as the Lord and Savior and give up their idol-worshipping religion. He looked at the introduction of English as a great hindrance to the development and progress of Indian society, from a Christian perspective.

2. Belief in the Efficiency of Vernaculars

Since the Reformation, Evangelical Christians around the world, that is, the Protestant Christians, have steadfast believed in the efficiency of and the need to use the vernaculars for spiritual matters as well as for governance. This resulted in the translation of the Bible into many vernacualrs around the world. The Jesuits and other Roman Catholic orders were not very keen about the translation of the Bible into local vernaculars since worship within their church used Latin until mid-twentieth century. Yet, the Roman Catholic missionaries (Jesuits, et al.) expended a lot of their lifetime to develop the vernaculars of the peoples to whom they ministered the spiritual matters, ethics and morals of Christianity. Thus, we notice that, even before the advent of the actual European dominion in India, the Christian missionaries were keen to develop the indigenous Indian vernaculars. Use of prose for written communication was popularized by these missionaries in many Indian languages.

3. William Campbell's Book

William Campbell's book was titled BRITISH INDIA. As it was the practice in the nineteenth century publications, there was also a subtitle or an explanatory part of the title, which read as follows: In its relation to the Decline of Hindooism, and the Progress of Christianity: containing remarks on the Manners, Customs, and Literature of the People; on the effects which idolatry has produced; on the support which the British government has afforded to their superstitions; on education, and the medium through which should be given.

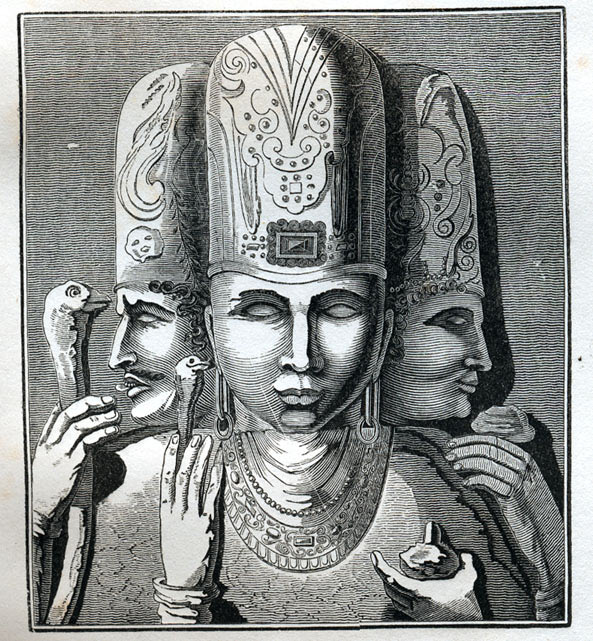

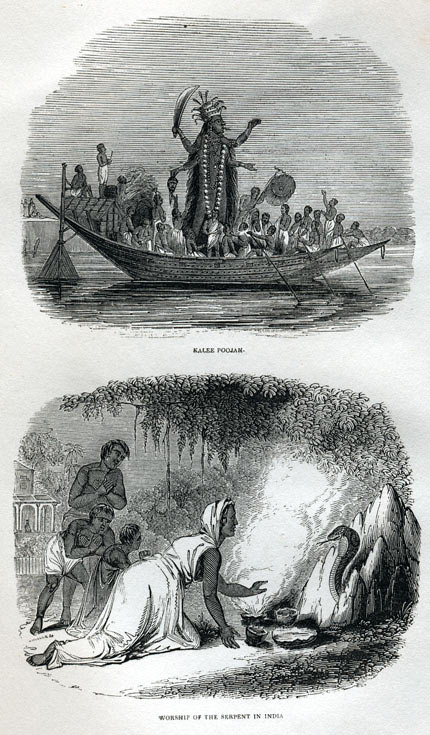

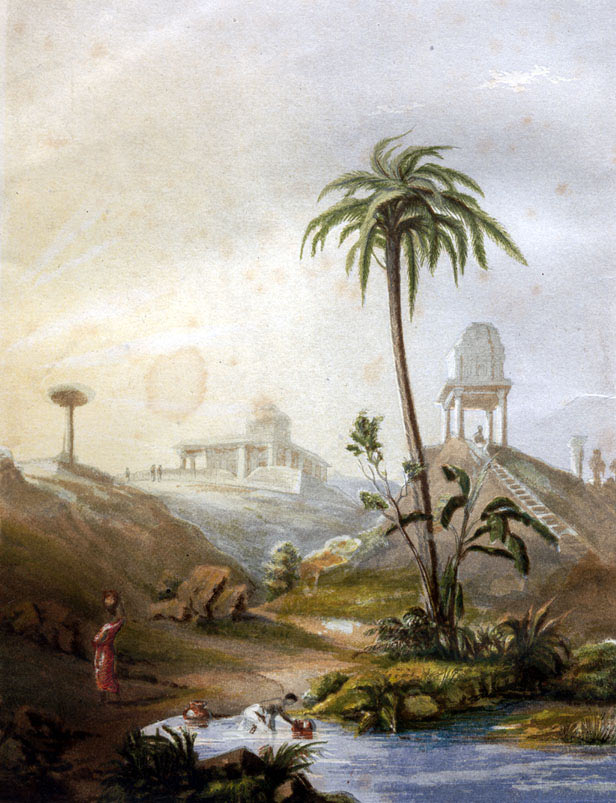

The book was published in the year 1839 in London by the publisher John Snow at 35, Paternoster Row, London. The volume has some interesting wood carvings of Hindu gods and goddesses as well as some water color paintings of scenes from India. The piece on Bangalore is reproduced at the beginning of this article above. (Can we reconize the Bangalore City of 1839 now?!) We reproduce also some of the visuals (wood carvings) contained in the book, as we go along.

4. Importance of William Campbell's Book - A Record of the Vernacular Party

Remember that the book was published in the first half of the nineteenth century, eighteen years before the break of the First War of Indian Independence, also called Sepoy Mutiny, in 1857. Like other missionaries, who served the people of India by opening schools and other progressive institutions for the betterment of Indian people, William Campbell was also anticipating, with a heavy heart, that one day Indians would become masters of their own destiny in a free land of their own. However, like other Christian missionaries of the period, Campbell was willing to face that situation, if that is what the Lord Jesus Christ has ordained for the Indian people. His concern was more with regards to the failure of the British officials to be faithful to the Bible in all walks of their life and in their dealings with the natives. Like other missionaries he thought that it was the duty of the British officials to help spread Christianity, which they did not because they themselves were becoming more secular due to the influence of their own background in England. He also felt that the introduction of English as the dominant language of education, governance, and public affairs would actually accelerate the process for rebellion and eventual overthrow of the British from their colony, much against the argument that this introduction would help Indians become loyal subjects of the Crown or the Company.

The two chapters presented here are the last two chapters of this big volume of 596 pages. Leaving aside William Campbell's enthusiasm and dedication for the propagation of Christianity in India, (a common goal to a large extent, even among those who wished to establish the supremacy of English; there are some differences between the two parites, but we will not dwell on this aspect here), one would clearly see his writing to be prophetic in many respects, relating to the linguistic behavior and preferences of the last 175 years in the Indian subcontinent.

Well ahead of his time, William Campbell shines before us as a great language planner, a great supporter of the Indian vernaculars. Most of his arguments will be repeated later on by the Indian patriots, not only during the struggle for freedom, but even now since India became a Republic. If anyone is stuck with his apology for Christianity only, then one may not be able to see the great foresight that Campbell had to anticipate things that would become a reality because English was introduced as the dominant language of education, governance, and public affairs, and developed into a government sponsored lingua franca for the nation.

William Campbell's forceful argument in favor of Indian vernaculars and opposition to English as the medium of instruction would be repeated time and again as soon as the Indian National Congress started practicing agitation politics under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. Annie Besant would make it her central theme in her Presidential Address of the Indian National Congress in early 1900s. The vitality of the vernaculars, their rich diction, bountiful literature, morals, ethics, and their function as the most effective tool to communicate the message of hope, construction and future would all become important elements of the Freedom Struggle. However, even as this strong elucidation of the virtues of the Indian vernaculars were repeated, English would assume a place of greater importance as the medium of communication between various linguistic groups, as the medium of education to impart science and technology to Indian students everywhere in the country. In the words of William Campbell, a process of becoming strangers in their own land had been embraced willingly by the ruling classes of India, and, as Andre Martine wrote, the eternal pursuit of the elite is the hall mark of every society, the lower classes of India also naturally clamored and clamor for English.

We reproduce the chapters as they are without any editing. However, we have taken the liberty to break the long paragraphs into shorter ones, with subheadings wherever necessary to facilitate reading this material. The subheadings given by us are given in red, whereas the original subheadings which the author gave for a few sections are retained in blue. We also take the liberty to give in bold certain statements that appear to have some bearing on what we experience today, or the statements that are very significant for an understanding of the development, growth and use of Indian vernaculars. Such emphasis is added by us. The original emphases on certain phrases and/or sentences given by Campbell are kept in italics as found in the original text.

CHAPTER XXVI

EDUCATION OF THE NATIVESNATIVE EDUCATION - THE USE OF THE VERNACULARS-PROMISES OF THE CHARTER-MONOPOLY OF INSTRUCTION-TESTIMONY OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY- AMOUNT OF GOVERNMENT PATRONAGE-ENGLISH LANGUAGE-PRINCIPLES OF RULE - SYSTEM OF CONQUERORS-EFFECTS IN ENGLAND AND IRELAND - ENGLISH PARTY AT CALCUTTA-INFLUENCE OF THIS SYSTEM UPON OUR RULE.

5. AGENDA - ELIMINATION OF IGNORANCE

IGNORANCE, there can be no question, is a curse to any people. Where the multitudes are illiterate, they are exposed to the wiles of the crafty, to the superstitious fears which their own fancies originate, to all the lies which their priests may propagate, and to all the alarms which the selfish agitator may excite. But when education becomes general, information spreads, and an acquaintance with men and things gains the ascendant; the people judge for themselves; ancient prejudices are removed; society is emancipated from the despotism of priest-craft; facts, truth and evidence gain dominion over the mind; and rational freedom is rendered secure. If the past history of the world has failed fully to substantiate these facts; the history of India will, I hope, very soon render them unquestionable.6. WORTHLESS NATIVE EDUCATION: LOADING MEMORIES

WITH INFORMATION THEY CANNOT UNDERSTANDAs it is at present conducted, no plan of education could be so worthless as that which obtains among the natives. To teach the children to read upon olas (Cajan leaves) [dried and seasoned palmyra leaves used to write books in the past, B.M. and M.S.T] to write, and to cipher; to load their memories with lessons which they cannot understand; to initiate them into their absurd system of idolatry; to instruct them in the history of their gods, and in the licentious nature of their worship, may be the best method for keeping them in error, but it can never produce those effects which the wise and the good wish to contemplate.

7. THE BEST IN THE NATIVE SYSTEM WERE ADOPTED BY MISSIONARIES:

USE OF NATIVE LANGUAGESThe missionaries saw this from the beginning. Convinced that education must become an important instrument for the furtherance of the gospel, and especially in preparing the people for the reception, of the truth, they established schools on a better plan. So far as the native system was good, they adopted it. Sets of school-books, containing the elements of history, geography, astronomy, &c., were prepared in the vernacular languages. In the use of catechisms, religious books, and especially the divine oracles, treasures of divine knowledge were enriching the minds of the rising generation, and were preparing them for the abandonment of idolatry, and for the examination of the Bible.

Thousands of children were educated in the Serampore mission schools; thousands in the Calcutta Baptist, and London Mission schools, and thousands more throughout the other presidences; and the brethren affirmed that, if they had funds, schools might be established to any extent. The children were not converted, but their prejudices were shaken; their parents appeared proud of the attainments of their sons; and many were overheard ridiculing the gods of their country. The reports of the School-Book Society can bear testimony to the popularity, and to the extent of education in former days: and had the same system been pursued, we might have had greater victories to record.

In the other parts of the country, and especially the Madras and Bombay presidencies, the improved system in the native languages, has been carried on, and as far as individual exertions might be expected to avail, the effects have been cheering; prejudice has given way both on the part of the parents and of the children; many have learned to value education as they never did before; a race are springing up to read our scriptures and tracts and books with facility; and a people are prepared to welcome the declaration of the truth.

I am not ignorant of the vast work which remains to be accomplished, and of the want of suitable teachers, agents and means to carry it on. No. When I think of the population of Hindosthan, and remember the efforts which voluntary association can make to bring the field into a state of culture; I am ready to sit down in despair, since it must be evident to all that, at the present ratio, we should never be able to perform the task.

But when I contemplate the resources and the promises of the government, and think, that, in order to reform its subjects, to fit them for the duties of their stations, to prevent the accumulation of crime, to render prisons and banishment, and gibbets and similar penalties unnecessary, and to advance the moral and intellectual happiness of all, it is one essential principle of political economy to diffuse knowledge and education over the face of society, I am ready to hope for better enactments than have yet appeared.

At the passing of the last charter, the following were the sentiments expressed by Lord Glenelg -- then at the head of the Board of Control -- in reference to that clause which promised that greater things should be done for education.

The great object that we all have in view is the conversion of India to Christ. Some think that this may be better accomplished in one way, and some another. My own opinion is that it will best done by the establishment of schools in which the children may be taught the principles of our holy religion, and thus comparing its worth and excellence with their own absurd and monstrous system, they may be led to renounce the one, and embrace the other.8. PROMISE NOT FULFILLED: WHY THIS IMPOSITION OF ENGLISH?

In the name of honour and consistency, how, I ask, has this promise been fulfilled? An act of the supreme council has declaredthat all the funds appropriated for the purposes of education, would be best employed on English education alone;9. MONOPOLY OF PUBLIC EDUCATION BY UPPER CLASSES

But has this edict been sanctioned by the government at home? Is there to be in India a monopoly of public education by the upper classes who are so able to pay for it, while the poor are to be consigned to their ignorance and degradation? Are the benefits of knowledge, instead of extending to the whole population through the medium of native schools, to be confined to a few English colleges where large sums may be expended to educate the wealthy, that they may be prepared to rule and tyrannize over their people?

Are we to be told that, on the principles of justice and truth, the maxims of the Norman conquest are to be revived, and the system of the dark ages to be renewed on the plains of India, and that the few who will bow to their masters, are to be regarded with peculiar favour, while the masses are to be delivered up to neglect and to the priests? Then, I cannot but deplore the narrow, impolitic and unreasonable principles on which the government act, and think that the public voice ought to be raised against such unrighteous measures.

10. LESSONS FROM THE PAST HISTORY

The description which is given by the historian Robertson of similar efforts made in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, will apply with equal force and propriety to the present exertions in India.

Schools, upon the model of those instituted by Charlemagne, were opened in every cathedral, and almost in every monastery of note. Colleges and universities were erected and formed into communities or corporations, governed by their own laws and invested with separate and, extensive jurisdiction over their own members. A regular course of studies was planned. Privileges of great value were conferred on masters and scholars. Academical titles and honours of various kinds were invented as a recompense for both. Nor was it in the schools alone that superiority in science led to reputation and authority; it became an object of respect in life, and advanced such as required it to a rank of no inconsiderable eminence. Allured by all these advantages, an incredible number of students resorted to those new seats of learning, and crowded with eagerness into that new path which was opened to fame and to distinction.But how considerable these first efforts may appear, there was one circumstance which prevented the effects of them from being as extensive, as they naturally ought to have been. All the languages in Europe, during the period under review, were barbarous. They were destitute of elegance, of force, and even of perspicuity. No attempt had hitherto been made to improve or to polish them. The Latin tongue was consecrated by the church to religion. Custom, with authority scarcely less sacred, had appropriated it to literature. All the sciences cultivated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were taught in Latin. All books with respect to them were written in that language. It would have been deemed a degradation of any important subject, to have treated of it in a modern language. This confined science within a. very narrow circle. The learned alone were admitted into the temple of knowledge; the gate was shut against all others, who were suffered to remain involved in their former darkness and ignorance.11. FAILURE OF THE BRITISH IN INDIA

More than six years have elapsed since the charter was passed; and what is the amount of exertion that has been made to realize our expectations? Mr. Adam, it is true, was appointed to enquire into the state of education, and he has executed his commission, and has presented his reports full of information, and of plans which, if well received, adopted, and carried into effect, would unquestionably be full of grace and advantage to India. But here, I presume, it has ended.

To quote the words of an intelligent speaker on this point,"Works of great national improvement are neglected; and, by similar neglect, the great moral laws of the country are broken down, and sunk in one general abandonment of all that is great, public-spirited, and virtuous in a people."

12. CRIME OF THE COURT OF DIRECTORS!

Yet this is not the fault of the natives - - they are eager for and highly capable of receiving instruction; nor is it the fault of the executive in India - for one with more paternal feelings, towards the country there does not exist; nor is it the fault of the civil servants, the best of whom are over-wrought, and have little time to devote to matters of general improvement.

The fault - the crime lies with the Court of Directors and the British government in not providing the means for the education of the people. This is the bounden duty of every government. It is by the discharge of this high moral duty that Prussia has raised her character amongst the nations - but not without a large and necessary expenditure.

I find in Berlin, seventeen shillings and sixpence allotted for the education of every child that would not be otherwise educated; and what is the amount annually allotted for the education of India? It is not a farthing for every child that would not be otherwise educated; and it will amount to little more, even although increased by all the sums placed at the disposal of the Committee of Public Instruction. It may be thought, that this is foreign to the object of the meeting; but if Englishmen are to suffer so long as the courts of justice are corrupt, it surely behoves us to enquire at what period we may expect an end of our sufferings, as this reform can only be effected by education.

And here let me quote the words of Mr. Adam, than whom India has not a truer, a more judicious, or a warmer friend:

While ignorance is so extensive, can it be matter of wonder that poverty is extreme, that industry languishes, that crime prevails, and that, in the adoption of measures of public policy, however salutary and ameliorating their tendency, government cannot reckon with confidence on the moral support of an intelligent and instructed community! Is it possible that a wise and a just government can a1low this state of things longer to continue? (The end of the quote is not indicated in the text.)13. HINDU COLLEGE IN CALCUTTA: DOWN FALL OF VERNACULAR EDUCATION

While vernacular education was making progress in Bengal, and the Marquis of Hastings and his lady were rendering it the greatest encouragement, and many were exulting in the effects which the schools were likely to produce; the Hindoo college was established, and was giving to the students an English education. For the first few years, entire failure seemed to threaten it, but the government came to its support. Encouraged by some effects which it ultimately produced, others no sooner adopted a similar method, and held out a high premium to the study of English, in the prospects of office and emolument, than the usual kind of education fell to a discount; there was a rush to those schools where English was to be obtained; the native schools which had hitherto been regarded with esteem, were looked upon with scorn and contempt; the demand for books in Bengalee began to fall, while that for English rose very high; and if my information be correct, the native :schools at Calcutta are now almost deserted; and very few think of sending their children to learn their own language.

14. A SAD PICTURE; A SUBJECT OF DEEPEST REGRET

To some, this effect is a matter of great rejoicing; to me, it is a subject of the deepest regret, and I shall be greatly mistaken if it is not found, in the future, that it has driven back our cause for fifty years.

When the frenzy is over, when the system has done incalculable mischief, and when many a dark and gloomy day has been prepared for Hindosthan, the good will see that they must return to the old system, and begin their march at the point where they forsook the right road. The children in the native schools were receiving western literature and science, through the medium of their own languages; and while they learned all that was good, there was nothing to hinder them from obtaining a respectable education, and from becoming blessings to others. But since that day, English is paramount.

In all the government schools and colleges, the children learn to read, to write, and to cipher in English; whatever instructions they receive, are given in the same language; every thing may be learned but Christianity; the teachers may give the students infidel books, and teach them atheism, but they dare not mention the name of Jesus; and such seminaries are to be established over Hindosthan. As this system was unfolding itself, and the government began to show it favour, the missionaries and the benevolent in Calcutta, might have rendered a most important service to the state and to Christianity.

Had they pursued their former course with greater assiduity and diligence; had they exerted all their powers to show that a useful, and respectable, and religious education could be given to the natives in their own language; had they remonstrated with the government, and pointed out some of the effects which would certainly arise from the new scheme; then, the system patronized by the Marquis of Hastings might still have triumphed; the languages of the people might have been rendered important, and have become now, as they must hereafter, the vehicle of western science and literature. But I appeal to all who are acquainted with the subject, whether the scheme of the government was not extolled to the skies; whether missionary schools were not established on the very same principles; and whether some did not stand forward as the strenuous advocates of the course which government, and the new committee of public instruction determined to pursue?

15. VERNACULAR OR ENGLISH OUGHT TO BECOME THE MEDIUM OF EDUCATION?

This leads me to the discussion of the important question, whether the vernacular language or the English ought to become the medium of giving education to the natives. I feel the greatest respect for those who have become the advocates of a system which I consider erroneous. I yield to them what I wish to claim for myself, -- a regard to the best interests of that people, and a conviction that whatever system will most effectually destroy their idolatrous errors, and establish among them: the kingdom of Christ, that must be the best, and ought to be adopted. Nay: as I was once an admirer of this theory, but was soon convinced that it was erroneous; and as I have only been a distant spectator of its working in Calcutta, without having at all mingled in the contest, I may, perhaps, be aLlowed to give a partial opinion upon the point.

To everyone who has investigated the subject, who has perused the documents that have been written, and who has observed the movements of society both in and out of Calcutta, nothing is more evident than that the advocates of English have stimulated the government to the measures which have been adopted, and that the government, on the other hand, have animated them to adopt the extreme views which are now entertained. Posterity, it is true, will be the best judge in the affair; but in the nineteenth century, after the experience of so many ages, with the history of the world before us, and having the ability to draw from the past, guidance and discretion for the future, it is not wise to enter upon a career of speculation, in the face of well-attested facts; nor to expect success in a race where disappointment has so often attended the best exertions.

16. ENGLISH FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF MORAL VALUE?

I may, perhaps, be told that we have nothing to do with the political bearing of the question. This I cannot admit: it is the business of every benevolent mind to look at measures which are professedly adopted for the moral welfare of any people, and to weigh the reasons, and, as far as possible, the operations and the results, in the balances of truth; and if he finds that such a plan will tend to defeat the I great object which he wishes to see accomplished, it is his duty lift up his voice against it, and to do what he can to prevent it. I regard then this question as having two important bearings-the one upon the present welfare of the people, and upon our Indian rule - the other upon their conversion to Christianity.17. RULE OVER THE PEOPLE IN THEIR OWN LANGUAGE

If there has been one principle which I have admired in the past government: of the honourable Company more than another, it has been the determination they have shown to rule over the people in their own languages. Whether the records are to be in Persian or in English is a matter of trifling importance; when compared with the question, how are the natives to be judged, to be governed, to be instructed to be elevated in the social scale, and to have their present and eternal welfare promoted.

It used to be a rule in the service, that no officer in the military department, is qualified to advancement, except he has studied Hindosthanee, and that no civilian, except he has attended the college, and has made progress in one or more vernacular languages, can obtain a situation of trust and emolument. These rules have been laid down on the principle, that the native dialect should be that of the government,- that it is the best and most direct way to the hearts of the people - that it enlists the sympathies, the passions, the prejudices, and the good feelings of the subjects on the side of their rulers - and that it gives to all in authority, a power which they could not obtain in any other manner. The experiment has been fully tried, and has succeeded well.

No person who has been employed in offices of state in India, has been more successful in his career, than the late Sir Thomas Munro. When he entered upon his duties in the Ceded districts, they were in a state of the greatest confusion; banditti were prowling among the people, like wolves in the forest; war and anarchy had dissolved the bonds which unite the parts of the social system together; neither peace, nor order, nor security were to be found. But in a few years, this diligent and enterprising officer brought all into subjection, established confidence among the various classes of the community, gave a stimulus to trade and industry, nearly doubled the amount of revenue, and rendered the province tranquil and happy.

By what means did he do so? He spoke and used the vernacular language as he would his own. He allowed no interpreters and no expounders of the law to stand between him and the inhabitants. Their complaints, their causes, their grievances were all heard, enquired into, and adjusted in their own tongue. He showed them sympathy and kindness, and in return, met with confidence, gratitude and affection. The birds of prey were scared into their hiding places, and could find no room for rapine and for plunder. The collector became the father and the friend of the people, and when he became governor of Madras, and was accustomed to visit these districts again, they gave him the hearty and the affectionate welcome that is due to a parent, and his name is embalmed; in their memories, and will live among them to future generations.

18. SIMILAR CASE EVERYWHERE IN INDIA - VERNACULAR IS THE BEST HELP

This is only a specimen: go through India - visit with me the north and south, the east and the west. Let us go to, the provinces, which have fallen one after another under our rule, and show me the territories where the collectors and all the judges have discarded the Persian and the English, and every foreign tongue alike in the administration of affairs; where they have adopted, in all their courts, and all their official intercourse, the language spoken by the people, and where, like men of honour and of truth, they have laboured to emancipate the poor from oppression and despotism; and I will show you the provinces where peace, and order, and. prosperity most prevail; where sympathy and confidence, and the best affections of our nature' are called into exercise between the rulers and the subjects; where feuds and rebellions, and deeds of darkness are almost unknown; and where civilization and improvement are making rapid advances in society.

19. ACCURSED SLAVERY, THE MUSLIM RULERS IN THE PAST, AND VERNACULAR GOVERNANCE

In the days that are past, a very different system from this, has, I am aware, been. adopted by conquerors. It must be a shocking usurpation that has not brought some good in its train to posterity. As it is the prerogative of the Almighty to bring good out of evil; so, unquestionably, out of the reign of oppression, insult and tyranny, there has arisen to future generations, some good which neither the advocates of the system, nor the sufferers under it, could have expected or foreseen. It is likely that the Africans who have been stolen from their country, loaded with chains and galled with bondage, may now, in the days of their freedom, bless God that slave-ships touched upon their coast, robbed them of their comforts, and brought them to the West Indies as bondsmen, since they have there heard of deliverance from sin, have obtained the liberty that is in Christ, and may become the instruments of carrying back these tidings to Africa, and of setting their kinsmen free. But no one, I presume, would, on these grounds, regard accursed slavery as a good, or plead for such a system as the precursor of freedom and happiness to men.

Now, I might, by trouble and expense, ferret out some good from the systems which former conquerors have adopted. I might expatiate on the conquests of Rome, and show that, in her rule of iron, and her subjugation of the surrounding nations, she imposed her language and her laws upon the people, and has thus "infused her terms into every vernacular language of Europe, and has immortalized her name and her character."

I might tell of the conquests of the Caliphs, and show how much the Mahommedan rule was indebted, in the dark ages, to "a celebrated decree that the Arabic should be the universal language of the Mahommedan world, so that, from the Indian Archipelago to Portugal, it actually became the language of religion, of literature, of government, and generally of common life." I might advert to the edict of Akbar, and show how he established the Persian as the language of business and of polite literature through his extensive dominions, and that this has identified the genius of his dynasty, with the language of the country (Dr. Duff, on the New Era of the English Language in India).

20. SHOULD WE GO THROUGH THE IGNOMINY, SHAME, AND OPPRESSION OF THE PAST?

But a heathen philosopher might reply to me, what then? are these the benefits which you propose to my people in exchange for their mother-tongue? Are these the privileges which you will confer upon posterity, for all the misrule, oppression, and calamities to which the empire must be subject in order to secure their enjoyment? Are we to pass through all the ignominy, the shame, and the degradation which the Romans, inflicted upon the Britons, and which Akbar has inflicted for centuries upon India, that after many generations, your names and your nation may be venerated and renowned? Such measures are only worthy of a barbarous age.

We live in the days of humanity and benevolence, when better principle should regulate our conduct, and when more respect should be paid to the rights and liberties of men. We shall be glad to receive your laws, your literature, and perhaps your religion; but if we must do so at the expense of our language, our national prejudices, and justice, and law, and right administered to our people as God and nature have given them a claim, then we wish you would wrap them in oblivion, or keep them to yourselves.

21. ERRONEOUS SYSTEMS OF THE PAST

Let us see what such an erroneous system has done for past ages. "But the English," says the historian,

had the cruel mortification to find, that their king's authority, however acquired or however extended, was all employed in their oppression; and that the scheme of their subjection, attended with every circumstance of insult and indignity, was deliberately formed by the prince, and wantonly prosecuted by his followers. William had even entertained the difficult project of totally abolishing the English language; and for that purpose, he ordered, that in all schools throughout the kingdom, the youth should be instructed in the French tongue, - a practice which was continued from custom till after the reign of Edward, III., and was never, indeed, totally discontinued in England. The pleadings in the supreme courts of judicature were in French; the deeds were often drawn in the same language; the laws were composed in that idiom; no other tongue was used at court; it became the language of all fashionable company; and the English, ashamed of their own country, affected to exCel in that foreign dialect.The very same has unquestionably been the experience of Ireland, Wales, and the Highlands of Scotland. As the authors of this new theory do, I might take the exceptions from the general rule, and might show how agreeable and how useful such schemes were to these countries. But I prefer an appea1 to the general sense of the people, to the evils which the workings of an erroneous theory has entailed upon their country, and to the good and the prosperity of which it has deprived them, Though they have been in the very neighbourhood of the conquering kingdom; though they have enjoyed every advantage which power and promise; commerce and friendly intercourse could afford, in order to reconcile them to the English language; though every worldly inducement has been held out to them, extensive establishments have been supported at an enormous expense to wean them from their own tongue, and every measure adopted to initiate them into the foreign one; what, after centuries of grief and vexation, what is the estimation in, which the English is held? What is the light in which the people view English judges, magistrates, interpreters, and English jurisprudence? They are all viewed as a badge of conquest and of inferiority; nothing but a want of power obliges the people to submit to the yoke; and, whatever privileges, the English may have brought in its train, it is still the conviction of the sufferers that these might have been secured, with the dominion of their own tongue, and with a more just and benignant system of rule.

22. ARE THE NATIVES OF INDIA DIFFERENT FROM OTHER OPPRESSED NATIONS OF THE PAST?

But I may be told that the natives of India are anxious that the English language should be used in the courts of law, in the. revenue department, in political correspondence, and in all the public offices of state. Such a statement may impose upon those who are ignorant of the condition of India; but it cannot upon those who are acquainted with its affairs. I allow that in Calcutta, there is a rage for English, and that, amongst the young men who are aspirants to office and to power, and who see that the tide is setting in, in favour of English, there are many who think that, if they wish for advancement, they must worship the rising sun; but what has this to do with the vast body of the people? Has it not always been found that a fraction has taken the side of the dominant power, and rendered its obsequiousness, a stepping-stone to office and to aggrandizement? If the government were to make the knowledge of English, a sine qua non, to place and to distinction, does not everyone see that the path is plain, and that the greatest admirers of the plan, must be the first in the race?

"The sole reason," says Dr. Duff,

why the English is not now more a general and anxious object of acquisition among the natives, is the degree of uncertainty under which they - the natives - still labour as to the ultimate intentions of government, and whether it will ever lead them into paths of usefulness, profit, or honour; only let the intentions of government be officially announced, and there will be a general movement among all the more respectable, classes (Trevelyan on Education in India)23. GAINING THE MONOPOLY, AND A NEW THEORY

Who can doubt it? In such a case, the few will try to gain the monopoly, and rule over their brethren according to law. As soon, therefore, as it was declared that all the sums expended by the government upon education, would be lavished upon English alone; as soon as it was whispered that the language of the conquerors would soon supersede the Persian, and would become the universal medium of transacting the business of the empire, and of course the high-road to office, and emolument; what a rush to the Hoogly college! what an increase to the number of students wherever the essential qualifications were to be obtained!

Was this to be wondered at? No. But the great wonder to me, is that a wise and a beneficent government, and that intelligent men, who, no doubt, wish the welfare and prosperity of India should be misled by such a momentary impulse of native feeling, should mistake this expression of a few at Calcutta, as the wishes of the vast body of Hindoos, and should be carried away, by this burst of popularity, to establish a system which the present generation, will ultimately condemn:, and which posterity will regard as Utopian. No one, who has read upon the subject can entertain a doubt that what has been termed the English party, wished and hoped and laboured to the last, that English wou1d become the universal medium for the transaction of public business.

24. WILL THE SYSTEM FAIL IF ENGLISH IS NOT USED?

One of the committee, who from being an orientalist, is said to have become an advocate of this new theory, is represented as stating that if the English was not to be used in every department, the system, would completely fail; and in all the records published by the new committee of public instruction, this change is taken for granted, and was to be speedily accomplished. No one can mistake the strain in which all the abettors of the theory have written upon the subject. Whatever might be the regard of the former committee to the learned and to the vulgar languages of India; no one would charge the committee appointed in 1835 with any partiality of this kind. No. English was their watch-word.

It became the shibboleth of their party. Persian was to be driven from the courts, but it was that the English might gain the ascendency. The vernaculars were too vile and too contemptible to receive a moment's attention in any discussion upon the matter. If they could all have been amalgamated into one and brought up to receive sentence, like a poor unhappy culprit before the tribunal, this committee would have blotted them out of existence at once, that the English might occupy the place of honour and of station; and that day, the peal of joy would have rung throughout the empire, as loud and as merry as at any jubilee.

Will posterity believe it, that, in a committee of public instruction, sitting in Calcutta, and discussing the great and important question, "what medium should be adopted to give a liberal education to the natives," the vernacular languages - those spoken by the masses of the people; never once obtained an audience, nor an advocate to allude even to their claims? I say posterity, because such an event, I presume, has never occurred in the history of mankind before!

25. STRANGE NEGLECT AND UNHAPPY CONSEQUENCES

But this strange neglect was attended with some happy consequences. The public was not an inattentive nor a silent spectator of this struggle between parties, and of the treatment which the vernacular languages had received. It awoke to the support of the injured; it raised its voice in their favour; it brought this very committee to make an apology for the contempt which it had shown to them; and, when the Persian was abolished, and the question of a successor was to be decided, it sent forth a sound so distinct, and so overpowering on the side of justice and of right, that it exposed the folly of substituting one foreign language for another; it brought in the vernaculars, as the channel of law and equity, victorious over their competitor; it induced this committee to speak a favourable word for the dialects which they had already, in purpose, consigned to oblivion; and it permitted them to take some credit to themselves foR coming in to the help of the wronged, when their own favourite had suffered a defeat.

26. A FAIR TRIAL FOR VERNACULARS OR A SIMPLE GIMMICK?

According to the decree of the governor-general in council, the native dialects were to have a fair trial; they were, for the present, to be employed in the judicial department, as well as in the revenue; and it was to be seen, during a year, whether they were media suited to administer law and justice to their people. I understand they are likely to come out of the ordeal triumphant; and after they have been fully tried by better judges, than those who have hitherto so ignorantly denounced them, they will be found, I doubt not, as suitable a medium for giving a liberal education in science, in philosophy and in religion, as they are in securing law, justice and prosperity to Hindoos.

But notwithstanding this defeat, the English party will not rest satisfied; they will soon return to the charge; and every means will be employed to establish the English throughout India, as the language of law and of rule.

(Lest it should be thought that I am unreasonable upon this point, and that there is not now the least reason for apprehension, since the vernacular languages have gained this triumph, I subjoin in this note, a letter from the secretary of the Bengal government to the committee of public instruction.

One of the most important questions connected with the present discussion, is that of the nature and degree of encouragement to the study of the English language, which it is necessary and desirable for the government to hold out independently of providing books, teachers, and the ordinary means of tuition. Your committee has observed that unless English be made the language of business, political negotiation, and jurisprudence, it will not be universally or extensively studied by our native subjects. Mr. Mackenzie, in the note annexed to your report, dated the 3rd instant, urges strongly the expediency of a declaration by government, that the English will be eventually used as the language of business; otherwise, with the majority of our scholars, he thinks, that all we 'do to encourage the acquisition. must be nugatory;' and recommends, that it be immediately notified that after the expiration of three years, a decided preference will be given to candidates for office, who may add a knowledge of English to other qualifications. The Delhi committee have also advocated, with great force and earnestness, the expediency of rendering the English language of our public tribunals, and correspondence, and the necessity of making known that such is our eventual purpose, if we wish the study to be successfully and extensively prosecuted.Impressed with a deep conviction of the importance of the subject,- and cordially disposed to promote the great object of improving India, by spreading abroad the lights of European knowledge; morals, and. civilization, - his lordship in council, has no hesitation in stating to your committee, and in authorizing you to announce to all concerned in the superintendence of your native seminaries, that it is the wish and admitted policy of the British government to render its own language gradually and eventually the language of public business throughout the country; and that it will omit no opportunity of giving every reasonable and practicable degree of encouragement to the execution of this project, At the same time, his lordship in council, is not prepared to come forward with any distinct and specific pledge as to the period and manner of effecting so great a change in the system of our internal economy; nor is such a pledge considered to be at all indispensable to the gradual and cautious fulfillment of our views, It is conceived, that assuming the existence of that disposition to acquire a knowledge of English, which is declared in the correspondence now before government, and forms the groundwork of our present proceedings, a general assurance to the above effect, combined with the arrangements in train for providing the means of instruction, will ensure our obtaining at no distant period a certain, though limited, number of respectable native scholars; and more effectual and decisive measures may be adopted hereafter, when a body of competent teachers shall have been provided in the Upper Provinces, and the superiority of an English education is more generally recognised and appreciated.)27. ENGLISH WILL BREED DISSATISFACTION AND DISAFFECTION

It will therefore be necessary to glance at the effects which such a system of policy will produce, and to warn the government against it. As soon as this new epoch arrives, dissatisfaction will prevail among the natives in general. English being constituted the chief recommendation to office, hundreds and thousands of meritorious men, scattered through the provinces, will find that it has been their misfortune to have been born a few years too early - that they must sink into utter neglect - that they have not been able to compete with their juniors in acquiring the language of their conquerors,- and that, though they possess every other qualification to render them useful, they have not the one which may throw every other almost into the shade.

What will be the effect of this feeling so universal throughout the community, pent up it may be from the view of the rulers, but diffusing a sense of injustice and oppression among all classes? It will teach them to hate and despise their governors, as well as the system which has been espoused; the very same complaints which Wales and Ireland have made, will become common; a high and broad wall of separation will be raised between the subjects and the European authorities; and the regulations which have raised the few to office and to wealth, will create heart-burnings - discontent and disorder will ensue- and these will lead to anarchy and revolution.

28. ENGLISH WILL NOT HELP A BOND OF UNION

LET EUROPEANS LEARN INDIAN LANGUAGESThe English party profess to see in the scheme recommended, a bond of union which will unite this Anglo-Indian section to our government, and identify their interests with ours. I may be very defective in vision; but the very reverse is apparent to me. No persons understand their own interests, and what is likely to work for their benefit, better than Hindoos. So long as business is carried on in the vernacular dialects, the Europeans are obliged to learn the languages. Sometimes they apply with great reluctance, to the labour; but they are under the necessity of doing it; and as interest and advancement depend upon their attainments, they have every inducement to persevere.

But what will be the result when all business is transacted in English? Such studies will be thrown aside as useless. As all the natives employed by the government will understand English, and transact affairs of importance among the people, they will become the stewards of the estate; and the Europeans will be enabled to dispense with all trouble and anxiety on the question of language. Superintendence will become the principal business of collectors, of magistrates, and judges; and instead of mingling with the subjects, their time and attention will be devoted to the native assistants. Whatever confidence and sympathy existed before between the governed and their rulers, will now be destroyed.

In vain will the former try to make known their complaints and their grievances to the latter. The channel of communication is cut off; The European officer, whose predecessor was accustomed to listen to the wailings of oppression, and to the wrongs inflicted upon the innocent by the native official, is now deaf to every complaint, and understands not the voice of the sufferer. The whole power and management must fall into the hands of those whom this system has formed to rule the country. Rebellions without number will be fomented, and will be carried into effect, without the least knowledge on the part of the government.

The state of India at the present period, ruling it on the old system, and with all the knowledge which Europeans have of the languages, has shown the critical position of our power, and the necessity there is for being constantly awake to danger and to intrigue; what will be the state of affairs when we are locked up in security, ignorant of the cabals that may be forming in our own houses, and by our own servants, and exposed, like strangers, in a foreign land? This very party on whom we should depend, would know their time; they could buy and sell their masters at their pleasure; they would know how to improve their position to drive the English from their shores, to emancipate their countrymen from a foreign yoke, and to secure the power and dominion to themselves.

29. EXAMPLE OF HYDER ALI AND TIPPU SULTAN

These are neither new, nor extravagant sentiments. "Tippoo Sultan," says Mr. M'Kerrell in his preface to his Carnataca Grammar, "was well acquainted with this - the Hindoo language of his state; and Hyder Ally, his father and immediate predecessor, was quite familiar with it. Both were men of stern and unrelenting dispositions, and little partial to their Hindoo subjects; but they knew mankind too well, not to be aware, that unless those who govern, be acquainted with the language of the governed, a set of, middle men will arise, who will ultimately become the scourges of the country."

"In adverting," says Sir John Colbourne, "to the delusion which has prevailed in respect to the character of the rural population of Lower Canada, and to the extraordinary fact, that a people, enjoying, under a mild government, benefits and advantages which were highly appreciated by them, had been prepared and extensively organized for a general revolt, and to blindly enter into the schemes of the factious individuals by whom they have been duped, without the knowledge of the local government, or doubt being entertained as to their loyalty or intentions, I consider it incumbent on me to observe that the executive government, has been, for many years, totally excluded, and cut off from all communication with the habitans, of every district; they being in the hands and under the control of avocats, notaries, and persons of the medical profession residing among them, have been corrupted by them, acting under the direction of Mr. Papineau and his faction, and an unrestrained and seditious press. I have no hesitation in conveying this expression of my opinion to her majesty's government, lest too much reliance should be placed on the promises and addresses of a most ignorant peasantry, that have been, for many years, under the control of ambitious and unprincipled individuals to whom I have alluded."

"The facts stated by Sir John Colbourne merit, certainly, the utmost attention. If a fusion of laws and language cannot be obtained, some means should certainly be devised of enabling the government to know what is passing among the governed. To be for years cut off from all communication with the governed, and in ignorance of the state of general feeling, gives a curious idea of government. Epicurus' gods enjoyed themselves in perfect indifference as to the joys and sorrows of mortals; but at all events, they knew something of what mortals were about."

30. LESSON FROM CANADA FOR INDIA

The circumstances of Canada, are a suitable warning to us, in reference to India. I foretell the danger. If the proposed system be persevered in, it will soon be the bane of our empire, and will deprive us of the opportunities of doing its in- habitants good. But suppose that these predictions will not be realised, and that, in accordance with such a policy, we are able to maintain our power in the East, what heart-burnings! what oppressions! what discontent! what anarchy and confusion! what commotions will not a government, conducted on such principles, create among the people? As I love our fellow-citizens in India, and wish their present and eternal welfare, I venture to warn her rulers of the consequences which must arise from such a course. Experience is not true; the history of the world is a falsehood; mankind have passed through so many revolutions in vain; if such a system will ever succeed, and if it be not attended with the most dreadful calamities to the people.31. THE CASE OF IRELAND

If any case could be more in point, than another, it is Ireland. Look at the dark history of that afflicted country. At the time when its interests became more identified with England, this system was really adopted. The English party gained the ascendency. Every thing that was Irish, was consigned to oblivion. Nothing was heard of but English supremacy, the English language, English law, literature, and science, and English establishments to advance learning and religion. A crusade was especially carried on against the Irish language; it was said to be a barbarous jargon; authority wished to bury it in the tomb; and every thing was printed in English. When any attempt was made to publish a translation of the scriptures in Irish, and works for the instruction of the people, it was opposed with the greatest violence, and the advocates of humanity were thwarted in all their exertions.

The complaints of the poorer classes, were disregarded. One rebellion after another plunged the country in blood and anarchy. Hatred, discontent, feuds, strifes and outrages continued to work in society. No sympathy, nor confidence existed between the rulers and the subjects. The people, regarded as "aliens in blood, in language, and in religion," were delivered over into the hands of their priests. Those who used their language, secured the road to their hearts; and while the English might have set them free, might have learned their tongue, and saturated it with science and theology, and might have won them over by kindness and love to the Protestant government and religion, they lost the opportunity; laid up, in con- sequence of this wretched system, immense stores of misrule and degradation for posterity; and con- signed the Irish people and their children to a superstition which now rules them as with a rod of iron. After centuries have passed away, what is still the state of Ireland?

CHAPTER XXVII

THE EDUCATION OF THE NATIVESUSE OF TERMS IN THE LANGUAGE-ENGLISH SYSTEM-ARGUMBNTS OF THE HEATHEN - IMPRESSIONS UPON THE PEOPLE - EFFECTS OF THE NEW SYSTEM UPON MISSIONARIES - EFFECTS UPON HINDOO STUDBNTS - INFIDELITY - LITERATURE OF WALES - HIGHLANDS OF SCOTLAND - IRELAND - THE FORMATION OF A LITERATURB - SUGGESTIONS.

32. IMPACT OF ENGLISH ON THE MORAL AND SPIRITUAL STATE OF HINDUS

HAVING in the preceding chapter, considered the effects which the English system is likely to produce upon our Indian- rule, and upon the temporal condition of the Hindoos; let us proceed to examine the bearing which it will have upon the moral and spiritual state of the community, and upon the interests of science and literature.

In all our plans and operations for the conversion of the heathen, it is well to be guided, as far as possible, by the rules of the New Testament, and by the example of the apostles. Whatever may be the differences in our state and circumstances, the dictates of nature, the voice of reason, and the lessons of the scriptures must be regarded. In their attempts to preach the gospel to the heathen, to communicate instruction to the rising generation, to disseminate divine knowledge by the translation of the scriptures and by the publication of useful works, through the medium of the vernacular languages; modern missionaries thought they were directed by experience, and by the example of primitive times.

On the day of Pentecost, they remembered that the Spirit descended upon apostles and evangelists, endowed them with the gift of tongues, and enabled them to address Parthians, and Medes and Plamites, and dwellers in Mesopotamia and in many foreign countries, on the mysteries of redemption. Why, we ask, was not the miracle wrought upon the hearers, rather than upon the preachers? Why, instead of granting the ability to speak so many languages to the few, did not the Almighty agent, grant the ability to the thousands assembled in Jerusalem, and to the vast multitudes in different lands to whom the message was to be proclaimed, to understand his servants who spoke probably the language of Judea?

The one miracle would have been as easy to him, as the other; but as it would not have been so much in accordance with nature, and with those general laws to which the Divine Being has attended even in the working of these wonders, he bestowed the gift of tongues. As he did not provide food for millions, when a sufficiency for thousands was all that was required, so he did not grant the gift of understanding the Hebrew or the Greek to the nations, when the other gift to the preachers, was sufficient to accomplish his purposes of love.

Though this endowment is not now continued to the church; yet the missionaries deemed it both more scriptural, and more reasonable, that they should toil to obtain the languages of the people, than that the heathen should, either in dozens or in multitudes, learn their foreign dialect; and when God gave them power to accomplish the task, when he commanded his blessing to rest upon their labours, and when idolaters were impressed with the word, they concluded, that they had additional arguments to persevere in their course.

33. VERNACULARS NOT FIT FOR THE TRANSLATION OF THE BIBLE?

But it has been said that the heathen languages do not, at present, contain terms adequate to convey Christian truth; and it will be better to wait till natives are educated and raised up, to introduce these terms into their own tongues. This is a very old objection.

Among the polished writers of Italy," says Hallam, "we meet on every side the name of Bembo; great in Italian as well as in Latin literature, in prose as in verse. It is now the fourth time it occurs to us; and in no instance has he merited more of his country. Since the fourteenth century, so absorbing had become the love of ancient learning, that the natural language, beautiful and copious as it really was, and polished as it had been under the hands of Boccaccio, seemed to a very false-judging pedantry, scarce worthy the higher kinds of composition. Those, too, who with enthusiastic diligence, had acquired the power of writing Latin well, did not brook so much as the equality of their native language. In an oration delivered at Bologna in 1529, before the emperor and the pope, by Romalo Amaseo, one of the good writers of the sixteenth century, he not only pronounced a panegyric upon the Latin tongue, but contended that the Italian should be reserved for shops, for markets, and the conversation of the vulgar; nor was this doctrine uncommon in that age."Can such men assert," says the mandate of Berthold, that our German language is capable of expressing what great authors have written in Greek and Latin, on the high mysteries of Christian faith and on general science. Certainly it is not; and hence they either invent new words, or use old ones in erroneous senses-a thing especially dangerous in sacred scripture."

34. PREJUDICE AGAINST VERNACULARS BORN OF HATE AND IGNORANCE

But if such an objection, whether made in former times or repeated now, is not the language of ignorance, it must be of prejudice, since the vernacular languages of India are as well qualified to convey divine knowledge, as the languages of Greece and Rome were of old. Did the apostles and evangelists, in their sermons and in their writings, draw their theological terms from the Hebrew, and use them in the languages of the heathen? Instead of employing the term Jehovah or Elohim to express the name of the Divine Being, did they not adopt "Theos" which was used among the Greeks, and "Deus," which was used among the Latins, and reclaiming the general name from the heathen, apply it to the living and true God?

I might pursue this argument with the terms adopted to express sin, conscience, salvation, heaven, hell, adoption, and justification; and did not the apostles take the general terms that were used by the Greeks, and by other nations in an idolatrous sense, and giving them a Christian signification, appropriate them to the doc- trines and precepts of Christianity?

By this example, modern missionaries have thought that they were justified in taking heathen terms, in giving them a Christian signification, and in making idolaters and Christians understand them either by an explanation, or by the connexion in which they are placed.

Nay more; when natives receive an English education, and understand our literature, science and theology; these missionaries cannot see what different plan they will adopt to give their own people the knowledge of the Bible. If instead of pursuing this mode, they attempt to saturate their vernacular tongues with terms from the English as the advocates propose, the barbarity will be extreme; and I will leave those who find such difficulty in pronouncing, our eastern words, to judge whether it will be a recommendation, or an act of self-denial to the natives of India to study our religion, when the tracts, the scriptures, and books will be filled with the harsh and disagreeable words which not one in a hundred of them will ever be able to pronounce.

In order to consign the Sanscrit to oblivion, Mr. Trevelyan labours to show, that the English language has passed through various gradations to its present stage of perfection; but from whence has it gathered its terms which are now applied to literature and science? Has it not been from Greek and from Latin-heathen languages?

And why may not the terms as well be taken from the Sanscrit - a language so copious, and so incorporated already with the vernaculars,- as from western languages whose sounds are so barbarous, and whose etymology is so unknown, to the natives of the East? It is right to speak with modesty of one's country and kindred; but surely it is no arrogant assumption to say that when European missionaries have, in addition to being born in Britain and having obtained an English education, they have studied Latin and Greek and Hebrew in their youth, and have acquired, from many years of labour, a knowledge of an Indian language, that they are as well qualified to introduce terms into these dialects, or appropriate those which will be suitable, as any of the students who may graduate at the Hindoo colleges in Calcutta.

35. EXAMPLES FROM SOUTHERN INDIA

Whatever may be the opinion of others, I cannot but regard this new system, and what has been said to support it, as an injudicious sally against the operations, and the progress of our missions in Southern India.

More than a century has elapsed, since the Danish missionaries landed at Tranquebar; adopted the plan which, as I have shown, was pursued in primitive times, saturated the Tamul language with terms to which they have appropriated Christian significations, and have written works which deserve well of posterity. British missionaries followed in their steps; and in the various translations of the scriptures which have been made into Tamul, Telloogoo and Canarese in the original works which have been written, and in the translations which have been made of English books, these terms have been used in the same sense; they have long since been rescued from heathenism, and applied to a Christian use; and they are well understood by the large Christian community who are scattered over the peninsula.

Since these terms, generally speaking, are of Sanscrit origin they might be used in Bengalee, or in Oordoo, as well as in the languages of the south, and might become common to our religion throughout our Indian empire; what then? Are the labours, the anxieties and the progress of ages to be thrown away? Is a system to be sanctioned and applauded, which is not only destitute of support from nature, reason, and scripture, but opposed to the genius of the languages, and to the efforts which have so long been successfully made? Are the principles on which Fabricius, Carey, Marshman, Martyn, Hands, Reeve, Gordon, and Rhenius, and many more have proceeded in the translations of the sacred volume to be discarded, and the oracles of truth to be filled with foreign terms which the people can neither pronounce, nor understand? If these are the theories, what must be the practical results?

36. WHY MAKE CHRISTIANITY A FOREIGN RELIGION BY TEACHING IT THROUGH ENGLISH?

It has long been an objection raised by the heathen against the missionaries, that Christianity is very well suited to England and to Englishmen; but that their own religion is best suited to Hindoos; what strength does this argument gather from the system espoused? "From the beginning," the Hindoos will say, "we have told you that your religion was not fitted for India. Some among yourselves have now confirmed us in this opinion, since they maintain that it cannot be understood in our languages. If we wish to comprehend your Bible, and your theology we must learn and study English; what cannot be explained in our language, never surely could be intended for us."

Indeed, the whole system is calculated to make the impression upon their minds, that it is altogether an English concern. Christianity was intended by its great author, for all languages, nations and kindreds of men. In primitive times, it brought liberty to the Jew and to the Greek, to the Barbarian and the Scythian, to the bond and to the free. But by human systems, how often has the light been obscured, and concealed from their view! During the dark ages, it was shut up in the Latin; and in the nineteenth century and in British India, the English is proclaimed to be the language without which our religion cannot be understood, its evidences cannot be appreciated, its beauties cannot be seen, and its power cannot be felt.

When such views are propagated; what are the suspicions they are calculated to excite? That our re1igion is an engine of the state - - that it is a part of our national policy - - that it is associated only with our rule - that it has come in to the support of our misgovernment, and all the grievances which may attend our administration - that up to the present time, they have heard very little about religion in English, but now the British think it is proper to consolidate their power, by engrafting their language and religion upon India.

37. CHRISTIANITY ABOVE ALL ETHNICITY AND LINGJUISTIC IDENTITIES

"This," they will say, "is just the old system. The Moguls gave us Persian and Mahommedanism; the Portuguese gave us their tongue and Popery; and now we have the English and Christianity." Now, I maintain that this is doing injustice to our religion. It does not require to be mixed up with any language, nor with any government in particular.

It is placing it in a false position, and is uniting in the minds of the people, what ought to be kept separate and distinct. So long as missionaries study and honour their language, and make exertions in Bengalee, in Tamul, and in Canarese; they are recognized as friends to Hindoos; there is a sympathy between them and the people in their sorrows, their trials and oppressions; they are regarded as a wall of defence to shield the helpless from injustice and rapacity, since they will not witness such evils and be silent; and they are everywhere known as the advocates of humanity and benevolence.

But the moment that we use our own language and mix up our religion with it, we appear as Englishmen; the strongest prejudices are raised against us; we are associated with the conquest and with the conquerors of their country. Our religion is only a part of the English rule, and with that government, it must wither and die. If they hate our authority, despise our laws, and complain of our taxation, they will also denounce our divinity.

Amongst the few, our language may be popular so long as their ambitious views are promoted; but once let other prospects be rendered more inviting and they would be the first and the most violent to abuse it, and to aim at its extermination. May that dark and dreadful day be far distant, when the British power will be overthrown in that land! But is it well to adopt plans whose principal importance is derived from the assumption that our rule is to be perpetuated among that people to many generations? Does not the history of the last two years, create within us fears and apprehensions?

On the old system, missionaries were in India before the British government was established, and obtained the respect and the confidence of native authorities; but what, in case of revolution, would be the fate of our language and of our religion as mixed up with it? They would both be swept away in a moment. The very sound would add inveteracy to the bitterness, and would give energy, to the malice of our foes.

38. CULTIVATE THE NATIVE LANGUAGES; INFUSE SCIENCE THROUGH THE VERNACUALRS

But cultivate the native languages; infuse our science, literature, and religion into every dialect; improve the time and the opportunities which Providence has afforded us, to give the heathen knowledge and Christianity, since we may soon be deprived of them; associate the religious views, principles, and experience of the people with the language in which they were nursed and educated; mix up the zeal, the sympathies, the passions, and the generous impulses of the native converts with the interests of their own country and kindred; and instead of imposing our language upon them, as a badge of their subjection and of our ascendency, let us convince them that it is our supreme wish to do them good, and to convert them to God, in perfect accordance with all their rights and privileges as men and as citizens; then, we establish our religion on a firm and enduring basis; possession is taken of the soil; Christianity is not dependent upon this language, nor upon that government, but it is incorporated with the best interests of the people and amidst the tempests of revolution, and the fall of dynasties, it will take root, and, like the oak amidst the trees of the forest, it will settle, will continue to grow, and will spread its branches till it fills the land.

The influence which this system is likely to have upon missionaries and others will be very prejudicial to the advancement of Christianity.

39. MISSIONARIES LEARNING INDIAN LANGUAGES

In former days, no sooner did a missionary enter upon his career, than he began to learn the language, and other important subjects engaged his attention. The phraseology that was used; the illustrations with which the natives clothed their thoughts; the figures, the comparisons, and the similitudes which were employed to elucidate the topics; their proverbs, their parables, their questions, their modes of expression, their looks and gestures-all that he could see and hear in the native language, were laid under arrest to imitate, and, as far as possible, to use, that the people might understand, and their attention be gained. His reason, his education, and his hopes of usefulness, demanded of him to lay aside his European fancies and prejudices, and to throw himself, as much as he could, among the people, to cultivate not only their language, but their manner and address.

But what is the influence which this English system is likely to produce upon our young missionaries? They find that they can dispense with the toil and the labour of learning a native language. To overthrow Hindooism, and to establish Christianity, the best scheme is to plant English seminaries, and to give the natives an English education. Not one in twenty who advocate this system, will ever obtain a vernacular tongue, so as to use it with any effect. So fully employed are their time and talents with English engagements that they have none to spend upon the language, the literature, the mythology, the customs, and habits of Hindoos.

40. TEACHING ENGLISH EVERYWHERE

Teaching in English absorbs every power, and has taken the place of the divine ordinance of proclaiming the gospel. Already nothing is heard of but the establishment of English schools at the mission stations, and many think to accomplish, by this new plan, the greatest wonders, though it be tried under very different circumstances from those of Calcutta, and conducted in a mode very different from that masterly style in which I understand Dr. Duff and his associates have carried on.

Infant schools are planted on the same system, and many of the children, it is announced, are able to read the New Testament in English. There is not a word said about their being able to understand it, and this, I venture to say, in the face of the church and of the world, they do not. What ridiculous fancies take hold of the minds of men! It were a subject fit to be caricatured, were it not, in another point of view, calculated to excite the deepest mourning and lamentation.