BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- English in India: Loyalty and Attitudes by

Annika Hohenthal, Ph.D. - Language In Science by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education by

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI AND MALAYALAM by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D.

- LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS IN TAMIL by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D.

- An Introduction to TESOL: Methods of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Transformation of Natural Language into Indexing Language: Kannada - A Case Study by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D.

- How to Learn Another Language? by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Verbal Communication with CP Children by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D. and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Bringing Order to Linguistic Diversity - Language Planning in the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- Lord Macaulay and His Minute on Indian Education

- Languages of India, Census of India 1991

- The Constitution of India: Provisions Relating to Languages

- The Official Languages Act, 1963 (As Amended 1967)

- Mother Tongues of India, According to 1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES FROM MARCH, 2001 - APRIL 2003

- INDEX OF AUTHORS AND THEIR ARTICLES FROM MARCH, 2001 - MARCH 2003

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org or send your floppy disk (preferably in Microsoft Word) by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road #320

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA. - Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2001

M. S. Thirumalai

SYNTACTIC CATEGORIES AND LEXICAL ARGUMENT STRUCTURE

R. Amritavalli, Ph.D.

1. Syntactic categories and argument structure

The guiding intuition of this paper is that differences between languages in the syntactic categories they instantiate may lead to parametric variation. The syntactic categories in a language constrain the possible argument structures of that language1. Hale and Keyser (1993), aiming to derive thematic functions from the LRS projected by lexical categories, assume the inventory N,V, A and P, corresponding to the semantic types of entities, events, states and relations.

Not all languages have all four of these categories, however. In particular, the question whether Adjectives are a category in Kannada (and Dravidian more generally) has been a matter of long-standing debate.2 Similarly, the so-called postpositions in Kannada and Malayalam may be nouns, or even verbs.3 Assuming, then, that Kannada and Malayalam reliably have only the two lexical categories N and V, the natural question that arises is: how does this restriction on the set of lexical categories affect the LRSs in these languages4?

2. Case and the category P

We begin with an observation in my earlier work, that a construction-type typical to our languages has a vestigial counterpart in English that is almost a word-for-word translation. Consider the English example (1) and the Kannada gloss for the English. All that is needed to obtain the Kannada Dative of Possession sentence (2) from this gloss is to put the Kannada words in the right order (leaving aside the there/pro difference).

(1) E There must be a lid to this K pro beeku ira ondu muccaLa -kke ida-

(2) ida-kke ondu muccaLa ira beeku '(There) must be a lid to this' (= this must have a lid) Now, the interesting point about these examples is that the English sentences regularly show an alternant with have, whereas Kannada does not. Descriptively, Kannada lacks the verb 'have'. So we have the English example (1') corresponding to (1).

(1') E This must have a lidOther triplets are listed in (3-4), of paired be/have possessive sentences in English, with corresponding dative of possession examples in Kannada.

(3) There is no end to this ~ This has no end (to it)

There are some advantages to this ~ This has some advantages (to it)

There is a sequel to this ~ This has a sequel (to it)(4) ida -kke kone illa.

this DAT end be-neg.

'(There) is no end to this.'ida -kke (ida -ralli) kelavu laabhagaLu ive.

this DAT (this LOC) some advantages are

'(There) are some advantages to this / in this.'ida -kke ondu TippaNi ide

this DAT a footnote is

'(There) is a footnote to this.'What is the difference between English and Kannada, which makes the dative of possession a marginal possibility in English but ubiquitous in Kannada? I had argued for a de-thematization of the to-NP position as a possessor position. In English, noting that this "extremely restricted" construction in English "is happiest when the possessor is inanimate or abstract, and the possessed NP is non-referential: thus there must be a cap to this is much more felicitous than *This is the cap to this." The alternation of be and have reinforced Kayne's analysis of have as a be incorporating a to. I suggested that be universally has an optional dative benefactive argument; the de-thematization of this argument position in English is due to the incorporation of to into be, to yield have.

This tells us why English has 'have' (and not the dative of possession), but it does not say why Kannada does not have 'have' (and has the dative of possession). Why doesn't the dative case incorporate into iru in Kannada?

There is an ill-understood relation between case markers and prepositions. Emonds (1985: ref?) treats case as P. Larson (1988) suggests that English to has the status of dative case.5 But why do we invoke the case-like status of to when we speak of its absorption? I am not aware of analyses postulating the absorption of genuine case in overt case-marking languages. Absorption seems to apply primarily to case destabilized in the course of syntactic change. The disappearing dative case is that which is a remnant in a language that has lost overt case and invented prepostions.

3. Postpositions and adjectives in Kannada

In the course of syntactic change, then, case-markers either strengthen into a new syntactic category P(reposition), or may get absorbed into existing lexical categories: into V, e.g. into be to give have; or even into N, to yield A. If so,we deduce that languages with case-markers do not have P, and do not have a verb have. Since these are usually OV languages, we deduce that the category "postposition" does not exist: it is not a P. Neither should these languages have adjectives, if adjectives are nouns which incorporate P. Thus there is an implicational relationship between P and A.

Recall our claim at the outset that Kannada has neither of these categories. Consider first the case for P in Kannada, as distinct from case. We have noted above the noun-like character of putative postpositions in Kannada (meele 'on', keLage 'below', madhye 'between'), in that they take genitive "objects" (positionally indistinguishable from "subjects") (5i), and can themselves be case-marked (5ii):

(5)i. ada-ra meele/ keLage /madhye

it-gen. top/ under/ centre

'on top of it/ under it/ (at) its centre'(5)ii. ada-ra meel-/ keLag- /madhyad -inda

it-gen. top under/ centre from

'from on top of it/ under it/ its centre'A second prediction for P-less languages is that they do not license complements to N or A (Emonds 1985:30).6 In this respect, Jayaseelan (1996) notes that "derived nominals" do not tolerate complements in Malayalam, and this is so in Kannada as well. The nominal counterpart of the verb 'to write' has no complement in (6ii), where its subject is genitive. A complement is possible only in a gerundive nominalization, with a nominative subject (6iii):

(6)i. avanu pustaka (vannu) bareda

'He wrote a book'

he book (acc.) wroteii. *avan -a pustaka baraha

*'His writing of a book'7

he - gen. book writingiii. avanu pustaka(vannu) barey-uvudu

'His writing a book'

he book (acc.) write-nom.Similar facts hold for such doublets as keeLike/ keeLuvudu ('query, asking'), heeLike/ heeLuvudu ('saying'), nooTa/ nooDuvudu ('look, looking'), oodu/ ooduvudu 'studies, reading', and so on. In general, gerundive nominals have the full range of sentential case-marking: they license nominative subjects, and the internal arguments of the verb as well.8 Projections of the N-category with the typical genitive NP specifier do not license complements. This again argues for the absence of P in Kannada.

Consider next the category of adjectives in Kannada. One argument against distinguishing these from nouns is that they both take the same range of specifiers. Iintensifiers in English distinguish these categories (Emonds 1985:18): we say how angry, but how much anger.9 We shall consider here for Kannada the very few underived adjectives such as oLLeya 'good,' which occur in their bare form prenominally, and must be suffixed with nominal agreement markers when they occur predicatively; hence these are among the best candidates for adjectives. (Most putative adjectives or adverbs in Kannada are clearly morphologically derived from nouns, either by dative suffixation to a noun (cf. udda - udda-kke 'height - to a height', i.e tall; kappu - kappige 'dark, black'), or by -aagi suffixation to a noun (sukha - sukhav-aagi 'happiness, happily'), where -aagi (lit. 'having become') is perhaps a complementizer ('as').) Compare the noun specifiers in (7i) with those for the putative adjective in (7ii), and note the difference in the translated glosses for the same intensifier in Kannada.

(7) i. avanige yeSHTu koopa!

'How much/ What anger he had!'

he-dat. how much anger

avanu yeSHTu koopiSHTa!

'What an angry person he was!' (lit. he how much angry person (m.)

How much of an angry person he was)ii. idu yeSHTu oLLeya yoochane! ‘How (*much) good a thought/ what a good this how much good thought thought this is!’

The distribution of isHTu 'this much', aSHTu 'that much' is similar across these categories.

(8) i. iSHTu / aSHTu akki ‘this much rice/ that much rice’

ii. iSHTu / aSHTu oLLeya akki ‘such good rice,’ i.e.

‘this good a rice’ (lit. this-much-good rice),

‘that good a rice’ (lit. that-much-good rice)

Again, intensifiers like bahaLa ‘very much,’ tumba ‘very many’, svalpa ‘little,’ saakaSHTu ‘enough, quite a few’, cooccur with N and A.

(9) i. bahaLa / tumba / svalpa / saakaSHTu jana

people

‘many people/ lots of people/ a few people/ enough people’

ii. bahaLa / tumba / svalpa / saakaSHTu doDDa (sthaLa, etc.)

big (place, etc.)

‘a very big place/ a very big place/ a slightly larger place/ a large enough place’

Turning to the question of complements to A in Kannada, these should be doubly prohibited, given that (i) Kannada lacks P, and that (ii) Kannada A is syntactically N, which (as we saw in (6ii) above) does not license complementation, again due to the lack of P. And indeed, the analogues of good to me, angry with me do not exist in Kannada.10

Our argument, then, is that P in English corresponds to the categories of Case and Noun in Kannada; and that A in English is again N, perhaps case-marked, in Kannada.11

4. The licensing of imperfect and perfect participles

Emonds (1985:40, n 18b) notes an intriguing correlation: "Languages which have 'serial verb constructions' often apparently lack PP structures." Why should this be so?

Let us return to the have~be alternation. Jayaseelan reminds us that have licenses and case-marks N; and shows that be licenses, but does not case-mark, A, which has an incorporated P (or case). Now recall the well-known difference between imperfect and perfect participles in English: Ving is a complement to be, but Ven is a complement to have.

(10) is eating has eatenThis fact in (10) is parallel to the facts about N and A complements to have/be, cf. (10'):

(10') be + Adjective have + NounLet us deduce from this that in English (i) Ving incorporates P or case ("is adjectival");

(ii) (consequently?) Ving does not need case to license it. Whereas Ven (i) does not incorporate P or case ("is not adjectival"); and (ii) needs case to license it.

We will now show that English does have a "serial verb" construction, with a gap in it that corresponds to the licensing requirement of these participles. That is, participial adjuncts in English attest imperfect but not perfect participles. We shall argue that in Kannada at least, the serial verb construction is a participial adjunct construction which equally permits all the three participles in the language: imperfect, perfect and negative.

First, let us observe the following facts about the serial verb construction in Kannada. The citation form of this construction is with perfect participles, and this is admittedly the most commonly attested type of serial verb.

(11)i. naanu maavinakaayi kitt-u toLe-du hacc-i tinde.

I raw mango pluck perf.part. wash pp. cut pp. ate

‘I plucked, washed, cut and ate a raw mango.’ (lit. having plucked, etc.)

The construction in (11i) has no English analogue. But Kannada also instantiates imperfect and negative participles in this construction:

(11)ii. naanu maavinakaayi kiiL-utt-a toLe-yutt-a hacc-utta kuNide.

I raw mango pluck pres.p. wash pr.p. cut pres.p. danced.

‘I danced, plucking, washing, cutting a raw mango.’

Notice that (11ii), in translation, looks quite acceptable as an English sentence: thus "present participles" or imperfect participial constructions have a parallel in English to the Kannada serial verb construction. This point is reinforced by the examples below:12

(12) E She came dancing, singing, strewing flowers

K avaLu kuNiyutta, haaDutta, hoogaLannu hariyutta bandaLu

She dancing singing flowers strewing came

E The storm came, uprooting trees, frightening people.

K aandhi bantu, maragaLannu biiLisutta, janarannu hedarisutta

storm came, trees uprooting, people frightening

Kannada has a negative participle that occurs in this construction. Once again there is an English parallel.

(13) naanu maavinakaayi toLey-ade hacc-ade tinde.

I raw mango wash neg prt cut neg prt ate

‘I ate a raw mango unwashed and uncut.’

The point (more generally) is that in the English participial adjunct construction, imperfect participles and negative participles (with un-) occur; perfect participles do not readily do so. Our claim is that adjuncts, which by definition are not externally case-licensed, instantiate only those participles with incorporated case, which do not require external case; hence English perfect participles are proscribed as adjuncts (except for passive participles with incorporated case, cf. the discussion below).

(14) She came dancing.

She came unwashed, unannounced, unnoticed.

*She came danced.

The explanation for (14) has long been that imperfect and negative participles are "adjectival" in English. Prenominally as well, perfect participles may not readily occur in English "because they are not adjectives":

(15) the dancing girl

the unwashed girl

*the danced girl

But the appeal to the categorial label "Adjective" here to distinguish imperfect from perfect participles actually reflects the different licensing requirements of these participles with respect to case-marking. Thus we cannot readily say that a participle in the verb phrase, in the perfect tense, "is an adjective." Yet English present and perfect participles differ in their licensing requirements in clearly verbal contexts, in precisely the way that reflects their ability to occur in "adjectival" (prenominal or adjunct) contexts. Perfect participles occur with have, which has the ability to case mark; they fail to occur prenominally or as participial adjuncts, suggesting that unlike adjectives, they do not have an incorporated case. Imperfect participles occur with be in the progressive tenses, as well as prenominally, and in participial adjuncts: all of these being positions in which no external case assignment takes place.

Considering now the Kannada "serial verb" data, which allow both perfect participles (in (11i)), and imperfect participles (in (11ii)), we can easily predict that perfect participles in Kannada must fully share the privileges of occurrence of imperfect participles, occurring in positions they are proscribed from in English. Let us look at the following contexts for the Kannada perfect participle:

(i) as a complement to be in the perfect tenses: both the perfect and the progressive tenses are formed with the auxiliary iru 'be' in Kannada. Compare (16) with (10) above.

(16) tinn-utt ide tin- d ide

eat imperf. be eat perf. be

‘is eating’ ‘has eaten’

(ii) in the serial verb construction: compare (11i) with (11ii).

(iii) as participial adjunct: Observe that we illustrate here the perfect and negative participles of an intransitive verb. We discuss the significance of this below: i.e., to the extent that English has corresponding perfect participles, they are "passive" participles.

(17)i. avaLu kuNiy-utta bandaLu.

‘She came dancing.’

ii. avaLu kuNi-du bandaLu.

‘She came danced.’ (She came, having danced.)

iii. avaLu kuNiy-ade bandaLu.

‘She came undanced.’ (She came without having danced/ without dancing.)

(iv) prenominally, as relative participles:

(18) i. kuNiy-u-va huDugi ‘the dancing girl’

ii. kuNi-d-a huDugi ‘the danced girl’ (the girl who danced)

iii. kuNiy-a-da huDugi ‘the not-danced girl’ (the girl who did not/does not dance)

These data suggest that in Kannada, unlike in English, perfect participles incorporate case, and do not need external case-licensing.

There is one well-known context in which English perfect participles do incorporate case: they "absorb" the verb's case, in the passive. Thus perfect participles found as adjectives in English have a "passive" interpretation:13

(19) cooked rice, washed clothes, (un)read booksBut perfect participles of intransitive verbs in English have no such luck; they remain without case incorporation, and so perfectives of intransitives do not usually occur as adjectival participles.

(20) *the come/ gone year (cf. the coming year; cf. also in the years to come),

*the walked man (cf. the walking man)

In Kannada, intransitive perfect participles occur as adjectives or relative participles, as already shown in (17-18) above. Cf. also:

(21) hooda varSHa (lit. the gone year, i.e. last year)

naDeda manuSHya (lit. the walked man, i.e. the man who walked)

Again, perfect relative participles of transitive verbs permit both an active and a passive interpretation.

(22) oodida pustaka the read book

oodada pustaka the unread book

oodida heNNu a read girl, i.e. an educated girl

oodada heNNu an unread (i.e. uneducated) girl

How do these observations about participle case bear on Emonds' observation about serial verb languages lacking PPs? We have suggested that P is a development from V's case. Then P-less languages, we speculate, still have case resident in only V, and crucially, V retains case in its participial forms. The only difference between participle and other verb forms would be their finiteness. (Thus participial forms typically have a negative element different from that which occurs in clauses, in English as in Kannada. In Kannada, the free neg illa cannot occur in relative or adjunct participles. In English, un and without can occur but not cannot: She ran away without (?not) dancing, unwashed (*not washed). When not occurs, have occurs as its licensor: She ran away, not having danced, not having washed.)

The occurrence of attributive, prenominal participles in Kannada is (again) not in conflict with our claim that Kannada does not distinguish A as a category. These privileges of occurrence we have sought to explain not in terms of category change as much as in terms of case-licensing. Given a more sophisticated theory of syntactic categories, we would expect the traditional categories to go the way of construction-types, which have no inherent theoretical significance.

5. Dative experiencer predicates as arguments of nouns

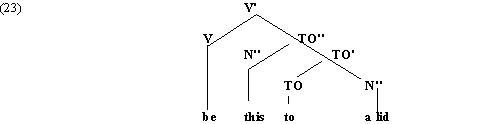

Let us return to the dative experiencer construction. Adopting Jayaseelan's (this conference) configuration for the position of Possessors and Experiencers, we have the following LRS for There is a lid to this or its K. translation idakke muccaLa ide:

The TO-phrase that the Experiencer occurs in the Spec of is a case phrase or a PP. This category is allowed to have an "internal subject" in the H&K framework. The "forcing of an inner subject" in the LRS, in Hale and Keyser's terms, is dependent on a category "being a predicate." Hale and Keyser consider P and A to be predicative, and thus allow the Spec of PP and AP to be occupied in their LRSs; but not the Spec of NP, or VP. (Nouns are not predicative; H & K treat the deverbal noun laugh as a product. Recall that N,V,A,P correspond for them to entities, events, states and relations.)

But to say that the Experiencer in (23) is licensed by virtue of the TO phrase is not the entire truth. Let us first observe the marginal existence in English of dative experiencer constructions such as the following, which easily translate into Kannada:

(24) A thought came to him.

ondu yoochane bantu avan-ige

Remembrance came to him. A memory came to him.

gnaapka bantu avan-ige ondu nenapu bantu avanige.

The marginality of the construction in English is evident in (25), which is (however) fine in Kannada:

(25) ? A/ The smell came to him. ??There came to him a smell.

(ondu) vaasane bantu avan-ige.

But the English examples in (25) significantly improve on expanding the noun phrase complement of TO, cf. (26). I.e., (25) improves when the 'predicative value' of the noun phrase complement of TO is increased.

(26) The smell of roses/ of fear/ of death came to him.

There came to him a smell of roses/ of fear/ of death.

This suggests that the Experiencer is actually licensed by, or is the "subject of,"' the noun phrase in (25-26). Indeed, typically, it is Nouns that seem to license Experiencer datives: cf. a puzzle to him, a bother to me, a blow to him (as in This has been a blow to him), a joy / comfort to us. This last phrase has a possessive alternant our joy and comfort, but the first four examples show that Experiencer datives do not always alternate with possessive arguments of Nouns.

Experiencer dative arguments of nouns alternate, rather, with the subjects of adjectival predicates. Cf.

(27) He was disappointed / This was a disappointment to him

was shocked a shock to him

was surprised a surprise to him

We were disgraced by him / He was a disgrace to us

We do not often notice the dative experiencer construction in English because it more often than not yields ground to the adjectival construction. But Kannada has no counterpart to the adjectival sentences in (27). This brings us back to the claim we made at the outset: we can now say that a language with few or no adjectives, which depends mainly on nouns to indicate states, will have Experiencer datives. Nouns in Kannada correspond not only to entities but to states.

REFERENCES

Amritavalli, R. 2000a. Lexical anaphors and pronouns in Kannada. Lexical anaphors and pronouns in selected South Asian languages: a principled typology, eds. Barbara Lust, Kashi Wali, James Gair, and K.V. Subbarao, 49-112. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Emonds, Joseph E. 1985. A Unified Theory of Syntactic Categories. Foris: Dordrecht.

Hale, Kenneth and Samuel Jay Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. The view from building 20: essays in honour of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 53-109. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1996. The serial verb construction in Dravidian. Paper presented at the seminar on Verb Typology, University of Trondheim (Norway), 12-14 September.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the Double Object Construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 335- 391.

Zvelebil, Kamil V.1990. Dravidian Linguistics: an introduction. Pondicherry: Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture.

NOTES

- We assume the position of Hale and Keyser (1993:76): "argument structures, or LRS [lexical relation structure] projections, are constrained in their variety by (i) the relative paucity of lexical categories, and (ii) the unambiguous nature of lexical syntactic projections."

- Cf. Zvelebil (1990:27, n.75, and the discussion in the text): "Among those who tend to deny or do deny the existence of adjectives as a separate 'part-of-speech,' the most prominent are Jules Bloch and M.S. Andronov. Master, Burrow and Zvelebil, on the other hand, accept adjectives as a separate word-class."

- Cf. Amritavalli (2000a:62): "Kannada postpositions are nominal in category: they take nominal case inflections, and the postpositional object is marked genitive." Jayaseelan (1996) notes a number of postpositions in Malayalam that have a verbal origin.

- Hale and Keyser in fact introduce a caveat to their assumption of "the traditional categories V, N, A, P" (p. 66), to say that these may not be universal (their n.6) : "In LRS representations, of course, we are dealing with the universal categories, whatever they turn out to be. Their realization in individual languages as nouns, verbs, and so on, is a parametric matter. Thus, the English possessive verb have, for example, is probably a realization of the universal category P, not V. But the Warlpiri verb mardarni, which most often "translates" English have, is clearly V, not P."

- Interestingly, this suggestion is again in the context of its absorption: in this instance, by a double-object taking verb (in a VP-internal passive operation, which derives the double object construction send Mary a letter.)

- Emonds makes a set of six predictions for an imagined P-less language. We consider here only the first.

- This of course has an interpretation as a compound, 'his book-writing', where book is not referential: *'avana nenne pustaka baraha' *'his writing of a book yesterday'.

- We speculate that nominative case-marking is by the 3p. neuter Agr element -du of the gerundive nominal. This agreement element appears in copula-less equative sentences with nominative subjects.

- Emonds identifies the following sets of elements for Spec(N) (Determiner) and Spec(A) (Intensifier):

- What is attested is the -aagi or 'as' complement, e.g. avanu nanage shatru-vaagi huTTida 'he was born (as) my enemy,' i.e. 'he was born an enemy to me.'

- English P also instantiates itself in complementizers. The Kannada complementizers anta 'that' and -aagi 'as' are deverbal rather than prepositional.

- Notice the word-order correspondences and differences. The positions of the finite verb (and its object, if any; cf. (11ii) above) are mirror-imaged in English and Kannada, as expected. But the serial verbs themselves are strung together in precisely the same order in both languages. This argues that there is no embedding of the verbs in the participial structure with respect to one another. Sentential complement embedding, on the other hand, shows mirror-imaging of the word order.

- Compounds such as well-read (however) occur in English both actively and passively: well-read books, well-read people.

HOME PAGE | BACK ISSUES | My daughter and I - Education for the Hearing Impaired | Lexical Choice by Media | Syntactic Categories and Lexical Argument Structure | ENGLISH IN INDIA: Loyalty and Attitudes | Urdu in Maharashtra | Strategies in the Formation of Adjectives in Tamil | Language News This Month: Politics of Language Education | SOME NEW BOOKS IN INDIAN LINGUISTICS | CONTACT EDITOR

R. Amritavalli, Ph.D.

Central Institute of English & Foreign Languages

Hyderabad 500 007, India

E-mail: jayamrit@eth.net.