AN APPEAL FOR SUPPORT

- We are in need of support to meet expenses relating to some new and essential software, formatting of articles and books, maintaining and running the journal through hosting, correrspondences, etc. If you wish to support this voluntary effort, please send your contributions to

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road Suite C

Bloomington

MN 55438, USA.

Also please use the AMAZON link to buy your books. Even the smallest contribution will go a long way in supporting this journal. Thank you. Thirumalai, Editor.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- COMMUNICATION VIA EYE AND FACE in Indian Contexts by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION

VIA GESTURE: A STUDY OF INDIAN CONTEXTS by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - CIEFL Occasional

Papers in Linguistics,

Vol. 1 - Language, Thought

and Disorder - Some Classic Positions by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - English in India:

Loyalty and Attitudes

by Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education

by B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI

AND MALAYALAM

by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D. - LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS

IN TAMIL

by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D. - An Introduction to TESOL:

Methods of Teaching English

to Speakers of Other Languages

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Transformation of

Natural Language

into Indexing Language:

Kannada - A Case Study

by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. - How to Learn

Another Language?

by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Verbal Communication

with CP Children

by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D.

and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Bringing Order

to Linguistic Diversity

- Language Planning in

the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- Lord Macaulay and

His Minute on

Indian Education - In Defense of

Indian Vernaculars

Against

Lord Macaulay's Minute

By A Contemporary of

Lord Macaulay - Languages of India,

Census of India 1991 - The Constitution of India:

Provisions Relating to

Languages - The Official

Languages Act, 1963

(As Amended 1967) - Mother Tongues of India,

According to

1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- MAY 2004 - INDEX OF AUTHORS

AND THEIR ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- MAY 2004

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org, or send your floppy disk (preferably in Microsoft Word) by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road, Suite C.,

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA. - Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2004

M. S. Thirumalai

A LEARNER'S INTRODUCTION TO MANDARIN CHINESE

Jennifer Verink

1. MANDARIN - THE OFFICIAL LANGUAGE OF CHINA

Mandarin Chinese is also called Putonghua, or "common speech". There are about 1,052,000,000 people who speak it in the world. It is the official language in China, and is also spoken in many other countries. It is said to be one of the most difficult languages to learn, as it has five tones and a complex writing system.

2. AN INTERNATIONAL LANGUAGE

Mandarin is spoken in many countries, including China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia (Java and Bali), Laos, Mauritius, Mongolia, Philippines, Russia, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United States and Vietnam. In 1999, there were 867,200,000 speakers in Mainland China. In all of the countries, there were a total of 874,000,000 first language speakers. The different dialects of Mandarin Chinese include Huabei Guanhua (Northern Mandarin), Xibei Guanhua (Northwestern Mandarin), Xinan Guanhua (Southwestern Mandarin) and Jinghuai Guanhua (Jiangxia Guanhua, Lower Yangze Mandarin).

3. DIALECTS OF CHINESE LANGUAGE

There are nearly one hundred local dialects of Chinese spoken. Therefore, before Mandarin became the "common language" of the people, it was nearly impossible for people from different regions of China to communicate with each other. It is said that at one point in time, the emperor decided to make all of his magistrates learn his language after he became frustrated at not being able to understand them at a meeting. This standard language was named "Yayu" in the time of Confucius.

4. GENETIC AFFILIATION AND HISTORY

During the Han dynasty, Mandarin Chinese was called "Tongyu" and it was then called "Guanhua" in the Ming and Qing dynasties. After the May 4th Movement in 1919, it was renamed "Guoyin". Then, in 1949, China was unified by the Chinese Communist Party, which was led by Mao Zedong, following periods of division altering with periods of renewed unity. The communist established government named this common language "Putonghua", which means "common speech". It is the name "Putonghua" which is translated into "Mandarin" in English. (Taken from the Chinese Morning website)

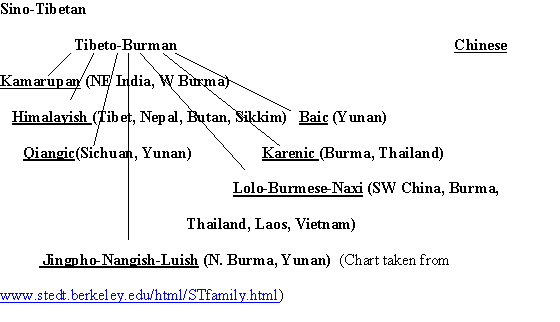

Mandarin belongs to the Sino-Tibetan family of languages. The following is a chart illustrating the different languages belonging to this family:

5. SOME SPECIAL CHARACTERISTICS

Mandarin Chinese has a few special characteristics. The first is its usage of tones, which serve to assign a distinctive relative pitch to words of similar sound, in order to indicate differences in meaning between them. Also, Mandarin is monosyllabic and uses little inflection.

Mandarin has been the official language of the Chinese government for centuries. It is what is usually taught under the name "Chinese" in schools outside of China. Also, it is one of four official languages used in Singapore. Elementary school systems in both the People's Republic of China as well as the Republic of China (Taiwan) have been created that are committed to teaching Mandarin. This excludes Hong Kong, where the language of education and formal speech remains Cantonese. However, even there, Mandarin is becoming increasingly influential.

Mandarin currently functions successfully as a form of communication at all levels of society throughout China. It is used in the mass media, government institutions, colleges and universities, companies, and for formal negotiations. It also has a presence on the Internet.

6. PROBLEMS SUGGESTED IN LEARNING MANDARIN

Some general problems suggested in learning Mandarin include its tones and writing system. This is especially true because Mandarin doesn't come from the same linguistic roots as English. Reading and spelling the romanization of Mandarin correctly could also pose a challenge. And learning how to pronounce the four (plus one neutral) tones clearly and correctly could also be difficult. In addition, it is necessary to understand and use the correct sentence structure in Mandarin as well as to be able to correctly and clearly listen to and speak the language.

7. DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ROMANIZATION

There are many different systems of romanization used for Mandarin. The most common are the Pinyin and Wades-Giles systems. Some other systems include the Latinhua Sin Wenz (no longer used), the Guoyeu Romatzyh (also called National Romanization. This is occasionally seen in Taiwan), Juyin II (seen on some street signs in Taiwan), Yale (developed in 1948 for the purpose of US military language teaching), and the Chinese P.O. System (an old system used instead of the Wades-Giles for some place names). The Pinyin system (also called "Hanyu Pinyin") was developed in 1958. It has been the UN standard from 1977, and is the official romanization system used in China and Western publications about China.

The Wades-Giles system was developed in 1859, and is currently the defacto system used in Taiwan for personal names.

8. THE CHINESE SCRIPT SYSTEM

The script system used in China is called "Hanzi". Both a simplified form and traditional form exist. The Chinese script system is logographic. This means that it uses characters as opposed to alphabets.

The script system was developed at least 6,000 years ago, according to the Chinese Morning website. Originally, it consisted of pictographs, but it eventually developed into a more mature writing system. This took place by the late Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC), as evidenced by the discovery of the "oracle bones".

The People's Republic of China (PRC) developed the simplified form of the script in 1956. This form is now used in both China and Singapore. The traditional form is used in Taiwan, Hong Kong and in overseas Chinese communities.

9. THE COMPOSITION OF THE HANZI SCRIPT SYSTEM

Composition of Hanzi is divided into six basic categories:

- hsiang hsing (direct pictorial representation)

- chih shih (symbolic rendering of abstract ideas)

- hui yi (combination of concrete pictorial elements with symbolic renderings of abstract ideas)

- hsing chieh (combination of phonetic and pictorial elements)

- chia chieh (character borrowed for its phonetic value to represent an unrelated homophone or near-homophone)

- chuan chu (character which has taken on a new meaning and an alternate or modified written form has been assigned to the meaning)

Of all six compositional forms, the pictophonetic form is the most powerful.

In an early dynasty dictionary, there were nearly 50,000 traditional characters represented. In a later dynasty dictionary, there are 9,353 traditional characters. One of the largest Chinese dictionaries contains about 56,000 characters. An educated person in China is able to recognize over 6,000 of these characters. In Taiwan, knowledge of 4,000 is necessary for reading a newspaper, but in China, knowledge of only 3,000 is adequate. The simplified form of written Chinese consists of 500 characters.

10. LEARNING THE CHINESE CHARACTERS AND THE SPOKEN LANGUAGE

Chinese characters are written in columns from top to bottom and from left to right. This method is still preferred in Taiwan, but the People's Republic of China has switched to the European style of writing left to right and top to bottom.

Learning to read and write Chinese can be very difficult. It requires mastery of a separate morphology (the study of structure and form of words) as well as memorization of several thousand characters.

The relationship between spoken and written Chinese is a complex one. This is compounded by the fact that there are numerous variations of spoken Chinese, which have gone through centuries of evolution since at least the late Han dynasty (202BC - AD220). The written language has changed much less than the spoken language during this time.

Wenyan (the classical or literary formal system of writing) differs from any of the spoken varieties of the language, much in the same way as Classical Latin differs from modern romance languages. Chinese characters that are closer to the spoken language are used to write informal works, such as colloquial novels.

Since the May 4th Movement (this was the beginning of the upsurge of nationalist feeling, along with unity of purpose among patriotic Chinese of all classes), the formal standard for written Chinese has been Baihua (vernacular Chinese). The grammar and vocabulary are similar, but not identical, to the grammar and vocabulary of spoken Mandarin.

The three dialects used in Taiwan, "Yi" (Mandarin), "Yat" (Cantonese), and "Tsit" (Hokkien), were derived from a common ancient Chinese word and share an identical character, but their orthographies (methods of representing the sounds of a language by written symbols) are not identical. The writing system for the Chinese language is largely independent of the sounds of the spoken language, and therefore can be used by speakers of all dialect groups.

There are many different scripts that have been used to write Chinese language. Other script systems include the Oracle Script (from the Shang Dynasty), the Bronzeware Script (from the Zhou Dynasty), the Seal Script (a result of the first emperor, Qin Shi Huang Di, and still used in artistic seals), the Clerk Script, the Wei Monumental Script, the Regular Script, the Song Style (used only in printing), the Running Script (Modern Chinese handwriting is usually modeled in this script.), and the Draft Script (an idealized calligraphy style).

11. MANDARIN SOUNDS

There are a total of thirty-eight vowel sounds used in Mandarin Chinese. These are also called "finals" in the Pinyin system of romanization.

There are a total of twenty-one consonant sounds in Mandarin Chinese. These sounds are called "initials" in the Pinyin system of romanization.

The four basic tones plus neutral tone are represented by the following symbols in the Pinyin system: first tone = "--", second tone = "/", third tone = "v" and fourth tone = "\". The neutral tone has no symbol. The first tone is high and level, moving from five to five in the chart below. The second tone is high and rising, moving from a three to a five. The third tone is low and rising, moving from a two to a one to a four. And the fourth tone is falling, moving from a five to a one.

Depending on the tone that a word is spoken in, the meaning can change drastically. For example, the word "ma" can mean "mother" (first tone), "numb" (second tone), "horse" (third tone) or "curse/scold" (fourth tone). It can also change the statement into a question (fifth tone). Someone desiring to learn Mandarin must really focus on learning the tones well, because depending on his or her tone of voice, the message that is conveyed could be completely different from what was intended. For example, the phrase "yi shuo shi", when said with one tone, could mean "poem", but when said with another it means "handful of dog feces".

There are a few tone shifts in Mandarin. The first third -tone shift occurs when two or more third-tone characters occur consecutively. In this case, the last character remains a third-tone, while the one(s) before it shift to a second tone. The second third-tone shift occurs when a first, second, fourth or neutral tone comes after a third-tone. In this case, the third tone mutates to a "partial third" tone, which means it begins low and dips to the bottom, but then doesn't rise back to the top. A tone change also occurs with the character for "bu". "Bu" is normally in the fourth tone, but when it comes before another fourth tone, it shifts to the second tone.

12. DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MANDARIN (CHINESE) AND ENGLISH

Although there are many differences between Chinese and English, there are also many similarities. Some of the pronunciations for the letters are the same. Also, at the elementary level, the sentence order is similar to English. Mandarin follows the order of "subject-verb-object" as well. For example, "I study Chinese" is "Wo xue hanyu" in Mandarin, which is literally, "I study Chinese". Also in Mandarin, as in English, the adjective precedes the noun that it describes. For example, "the big hotel" would be "da fandian", which is literally, "big hotel". However, unlike in English, verbs in Mandarin do not change tense. Instead, the tense is indicated by time words such as "yesterday", "tomorrow", etc… Also, unlike in English, in Mandarin there are no verb conjugations, plurals or articles.

13. PERSONAL AND PLACE NAMES

Personal names are very important in the Chinese culture and are chosen very carefully. This is because the names are supposed to influence a child's destiny. The last and middle names are already settled. However, the first name is chosen by the family. Some common first names in China are "Wen" (culture, writing), "Zhi" (will, intentions; emotions), "Yi" (cheerful), and "Ya" (elegant). Girls' names often involve flowers and beauty, while boys' names are related to brightness, intelligence and strength. (http://www.logoi.com/notes/chinesenames_number.html) The characters associated with the names give clues as to their meaning or significance.

Surnames are almost always used to address people in China. The surnames used can be different, depending on the relationship between the two people or on the situation, whether it is formal or informal. When friends address each other, they will usually use "xiao" (young) or "lao" (old). For example, a friend named "Fei Huang" may be known informally as "xiao Fei Huang", and an older man who sells you lunch every day may be known as "lao Liu" (old Liu).

Place names also have special significance in China. The following is a list of five place names, along with their origin and/or meaning:

- Shanghai ("above the water") - "Shang" means "above, higher, upper, etc… "Hai" means "sea". Shanghai is built close to the East China Sea, just above the water.

- Sichuan ("Four Rivers") Province - Sichuan is a basin with many rivers in it. The character "chuan" means river, but it is not as commonly used as "jiang" and "he".

- Yunan ("South of the Clouds") Province - Yunan is located to the south of cloudy Sichuan province.

- Taiwan Island (literally "Platform Gulf") - By tradition, the name came from a Chinese transliteration of the name that one of the native tribes applied to foreigners: "Taian".

- Guanxi ("Wide West") Province - The current Guanxi province is a contradiction of the ancient name, Guangdong, Xilu, meaning "Wide South, East Route", referring to present Guangdong's role as the eastern route from early China's core lands to the lands in the south. (Taken from www.washburn.edu/cas/history/stucker/chGeogMeaning.html and www.afe.eaasia.columbia.edu/china/geog/placenames.htm.)

14. ONOMATOPOEIC WORDS

Onomatopoeic words are words that name a "thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it" (Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. 1997.) Chinese onomatopoeic words differ from those in English. For example, in Mandarin, the sound a sheep makes is vocalized as "mie1mie", rather than "baaa baaa" in English. Also, a tiger would say "ao1wu1" in Mandarin, rather than "roaaoaaoaar".

15. GESTURE AND OTHER TYPES OF NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Gestures in China also differ from gestures used in the US. For example, when the Chinese refer to themselves in gesture, they do not point to their chest, like we do here. Rather, they point to their nose with their index finger. This is because our culture is a "feeling culture", while their culture is a "thinking culture". Therefore, we point to our hearts, while they point to their minds to represent themselves. Also, in China it is possible to count from zero to ten using only one hand. This is not possible in our American way of using our hands for counting.

In most cases, a visitor to China will not offend the locals by using foreign gestures. However, there are a few that you might want to avoid. When motioning for someone to come to you, make sure that you do so with your palm facing down. In many countries such as China, motioning with the palm facing up is used only for dogs and prostitutes. Also, although shaking hands is becoming a more popular form of greeting in some more westernized parts of China, the bow is still very prevalent. This bow differs from the Japanese bow, in that it is not very deep. It only involves a dip of the head and the shoulders.

Physical contact between men and women in China was once considered completely indecent in public. However, it is becoming more widely accepted, as western influence continues to spread. Still, to most Chinese, hugging and kissing in public may be incomprehensible, unless they have spent time abroad.

In interpersonal relationships, it is very important to remember the concept of saving and losing face, which is virtually non-existent in our culture. To lose face is to lose your respect, composure, etc… The easiest and worst way to lose face is to get angry, because this shows that you have no control over the situation or over yourself. Therefore, it is important for foreigners not to get angry with any of the Chinese people. Rather, it is better to take a deep breath and be patient. Another effective tactic is to simply cry (not sobbing, but shedding a few tears) because some Chinese people can be rendered defenseless by a foreigners' tears.

16. TO CONCLUDE

Even though Mandarin Chinese is a very difficult language to learn, learning Mandarin is necessary if a person wants to be able to speak the heart language of the people in the countries where it is spoken. By studying the language, one can also learn a lot about the culture as well. And it is not an impossible task, even though a foreigner will never be able to speak as fluently as a native speaker.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chinese Morning.com. www.chinesemorning.com.

The Chinese Outpost. www.chinese-outpost.com.

Lee, Phillip Yunkin. 250 Essential Chinese Characters For Everday Use. Tuttle Publishing Company. Boston, MA. 2003.

Rudelson, Justin and Qin, Charles. Mandarin Phrase Book. Lonely Planet Publications. 2000.

"The Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus" - http://stedt.berkeley.edu/html/Stfamily.html - designed by David Mortensen, based largely on content written by james A. Matisoff and originally presented on the web by John B. Lowe and Ju Namkung.

"Understanding Chinese Place Names" - Washburn University - http://www.washburn.edu/cas/history/stucker/ChGeogMeaning.html.

Zhongwen.com. www.zhongwen.com.

CLICK HERE FOR PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION.

APABHRAMSHA - AN INTRODUCTION | LITERATURE, MEDIA, AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION - Andhra Experience | BHARATHI - A COMMON SCRIPT FOR ALL INDIAN LANGUAGES | PHONOLOGICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS OF ORIYA SPEAKERS LEARNING KANNADA | A REVIEW OF AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL TEXTBOOK TO TEACH ENGLISH IN INDIAN SCHOOLS - FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF A NATIVE SPEAKER OF ENGLISH | A LEARNER'S INTRODUCTION TO MANDARIN CHINESE | COMMUNICATION VIA EYE AND FACE IN INDIAN CONTEXTS | STRATEGIES IN THE FORMATION OF COMPOUND NOUNS IN TAMIL | HOME PAGE | CONTACT EDITOR

Jennifer Verink

C/o. Language in India

Send your articles

as an attachment

to your e-mail to

thirumalai@bethfel.org.