BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- English in India: Loyalty and Attitudes by

Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education by

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI AND MALAYALAM by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D.

- LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS IN TAMIL by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D.

- An Introduction to TESOL: Methods of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Transformation of Natural Language into Indexing Language: Kannada - A Case Study by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D.

- How to Learn Another Language? by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Verbal Communication with CP Children by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D. and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D.

- Bringing Order to Linguistic Diversity - Language Planning in the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- Lord Macaulay and His Minute on Indian Education

- Languages of India, Census of India 1991

- The Constitution of India: Provisions Relating to Languages

- The Official Languages Act, 1963 (As Amended 1967)

- Mother Tongues of India, According to 1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES FROM MARCH, 2001 - MAY 2003

- INDEX OF AUTHORS AND THEIR ARTICLES FROM MARCH, 2001 - MAY 2003

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org or send your floppy disk (preferably in Microsoft Word) by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road #320

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA. - Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2001

M. S. Thirumalai

THE ARGUMENT STRUCTURE OF 'DATIVE SUBJECT' VERBS

K. A. Jayaseelan, Ph.D.

1. THE REPRESENTATIVE STRUCTURE THAT EXPRESSES "BEING HAPPY/SAD/HUNGRY/ANGRY."

Consider the following Malayalam sentences and their English glosses:

(1) en-ik'k'∂ santooSam uND∂ I-dat. happiness is 'I am happy.'

(2) en-ik'k'∂ wis'app∂ uND∂ I-dat. hunger is 'I am hungry.'

(3) en-ik'k'∂ (awan-ooD∂) deeSyam uND∂ I-dat. he-2nd dat. anger is 'I am angry (with him).' We may take the structure illustrated by the Malayalam sentences here as representative; for it is this structure that a great many of the world's languages use, when they express ideas like 'being happy/sad/hungry/angry'.

The contrast of this structure with the corresponding English structure has been discussed a great deal under the rubric of "quirky Case subjects." What has caught the attention of linguists here is the Case contrast: dative Case vs. nominative Case on the Experiencer argument. But there is another consistent contrast here. English has an adjective where Malayalam has a noun.

This second contrast (to the best of my knowledge) has never been focused on, for whatever reason. But it will be my contention in this paper that there is a dependency between the adjective/noun choice and the dative/nominative choice for the Case of the "subject." I shall also claim a relation between these two choices and the BE/HAVE choice in English, investigated by Freeze (1992), Kayne (1993). I shall suggest that there are three possibilities for languages to express notions like 'being happy/sad/hungry':

(i) to-DP be NP

en-ik'k'∂ santooSam uND∂

('To me happiness is')(ii) DP(Nom.) be AdjP

'I am happy/hungry.'(iii) DP(Nom.) have NP

'I have (great) pleasure/an appetite.'All three patterns (I shall try to show) are derived from the same underlying thematic structure, by different choices of incorporation.

Before we proceed, a fact should be noted: It has often been observed that Dravidian languages probably have no adjectives; they appear to fulfill the adjectival function by using participial forms which are transparently deverbal, or by nouns (Anandan 1985). But the absence of the category of adjective in Malayalam, as opposed to its availability in English, is not the explanation for the 'adjective/noun' contrast noted above; the explanation is deeper and more interesting, as I shall try to show.

The fact that some languages of the world do not have the category 'adjective,' suggests a line of thinking: suppose 'adjective' is not one of the basic categories of human languages. Consider the possibility that even in English, adjective is a derived category. There are some fairly transparent cases here, e.g. the adjective asleep; which is derived from a preposition and a noun:

(4) at + sleep → asleepThus, if English permitted a sentence like The child is at sleep, we would say that the complement of the copula is a PP; but in The child is asleep, we say that the complement is an adjective. We shall argue that several other English adjectives, e.g. happy, hungry, angry, are derived by the incorporation of a noun into a preposition.

2. THE STRUCTURE CORRESPONDING TO THE POSSESSSIVE THETA ROLE: MODIFICATION OF THE HALE-KEYSER PROPOSAL

Our analysis takes off from Kayne's (1993) account of the BE/HAVE alternation. Kayne bases his analysis on some facts regarding the behavior of the possessive in Hungarian described by Szabolcsi (1983), and on Szabolcsi's analysis of these facts. In Hungarian, the possessive construction has a verb van which can be translated as 'be'. It takes (according to Szabolcsi) a single DP complement, which contains the possessive DP. The possessive DP occurs to the right of (lower than) the D0 head of the be's complement. The full structure is as follows:

(5) … van [DP Spec D0 [ DPposs [ AGR0 QP/NP ]]]If DPposs stays in situ, it has nominative Case. But if it moves to Spec of D0, it gets dative Case; it may now move out of the DP entirely, but the dative Case is retained. If D0 is definite, the two movements mentioned above are optional; but if D0 is indefinite, these movements are obligatory. Thus the possessive construction in Hungarian would be (something like) To-John is a sister.

Kayne claims that the English possessive construction has a substantially parallel underlying structure, with just a few parametric variations. The verb is an abstract copula, BE; which takes a single DP complement. A difference is that English has a nonovert "prepositional" D0 as the head of this DP, which Kayne represents as D/Pe0. The structure is:

(6) … BE [DP Spec D/Pe0 [ DPposs [ AGR0 QP/NP ]]]In English, AGR0 cannot license nominative Case on DPposs, which therefore moves to the Spec of D/Pe0. But the latter also cannot license dative Case; so DPposs must move further up, to get nominative Case in Spec,IP. The "prepositional" D0 obligatorily adjoins to BE in English, and is spelt out as HAVE.

(7) D/Pe0 + BE → haveThe idea that have is be with a preposition incorporated into it is adopted from Freeze (1992).

We shall adopt a slightly different structure for the possessive construction. Assuming the Hale-Keyser proposal that theta roles are to be defined as positions in structural configurations, let us ask the question: What is the structure corresponding to the possessive theta role? Obviously, functional elements like AGR0 and D0 cannot be part of a configuration that determines a theta role; therefore in (6), DPposs cannot have as its base position the Spec of AGR0. The AGR projection, if it must be postulated, must be higher. However the copula BE may be an essential part of the configuration in question. We shall also assume, differently from (6), that D0 and P0 are heads of separate projections; and that a D0 may not be generated at all if the DP is indefinite. (But P0 may obligatorily adjoin to D0 if the latter is generated.) The theta configuration for the Possessor we assume is the following:

(8) BE … [PP DPposs [ P QP/NP ]]The space indicated by '…' implies a claim that a theta configuration need not be strictly local: in the particular case (8), functional heads like AGR0 and D0 may intervene between BE and the PP.

The P in (8) simply indicates a relation between DPposs and QP/NP. We must assume that it is not the same P that in Kayne's analysis "licenses" a dative Case in its Spec position; the reason for saying this is that DPposs in Hungarian obviously must move before it gets the dative Case. The Case-licensing P (then), which we shall notate as Pdat, is presumably a pure functional head generated in the space indicated by '…' in (8). But to simplify our subsequent discussion, we shall ignore all the elements generated in '…', including Pdat; in fact we shall 'pretend' that the P in (8) is Pdat. No harm will result, if we bear in mind that the movement chains that we speak of may actually have more links than we have indicated.

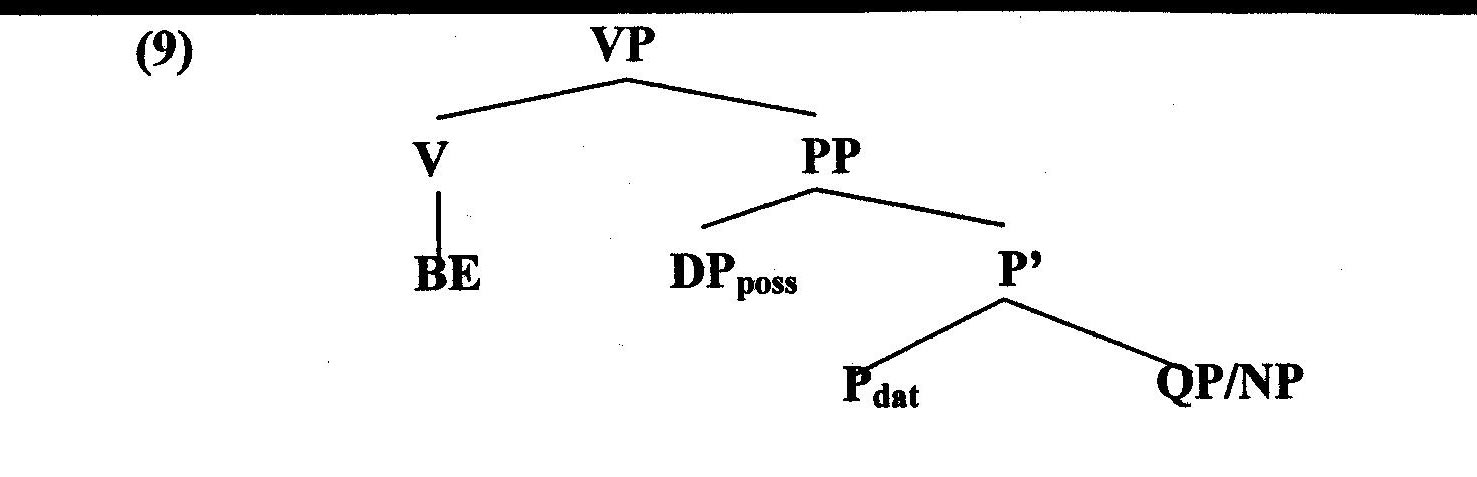

We operate (then) in terms of the following structure:

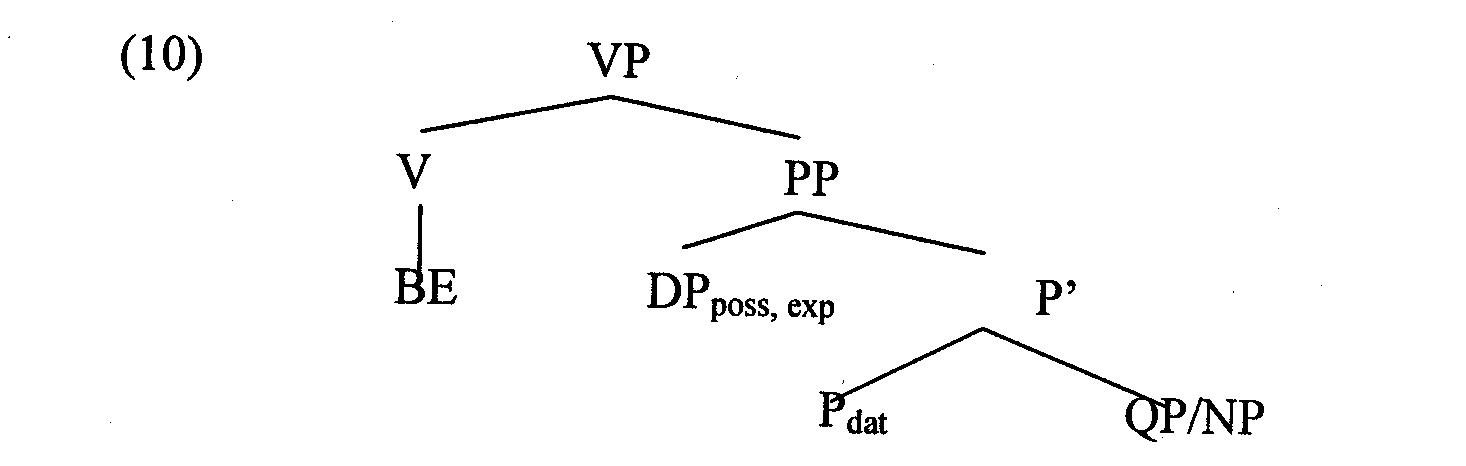

We suggest that this is also the configuration for the Experiencer theta role, a claim which would be in line with the observation that the theta roles available to Language are quite few in number owing to their being limited by the number of distinctive configurations available (Hale & Keyser 199?). Therefore, (9) may be revised as (10)1:

The Kayne claim is that in English, Pdat adjoins to BE and we get have; and DPposs then moves to the Spec of a higher functional projection to get nominative Case. We suggest that something else can happen in (10): when the complement NP consists of only an N, it may adjoin to Pdat and be realized as an adjective.

This hypothesis explains a fact noted in Kayne (1993), namely that have cannot take an adjectival complement:

(11) John was /* had unhappy.Note that if be can take an adjective, and if have is derived from be, it is prima facie surprising that have cannot take an adjective as its complement. But we now see why this is so: it is the same Pdat that either incorporates into be to yield have, or is adjoined to by a noun to give us the adjective.

We also explain the three possibilities (repeated below) for expressing notions like 'being happy':

(i) to-DP be NP

en-ik'k'∂ santooSam uND∂

('To me happiness is')(ii) DP(Nom.) be AdjP

'I am happy/hungry.'(iii) DP(Nom.) have NP

'I have (great) pleasure/an appetite.'If Pdat remains independent, it licenses a dative Case on the Experiencer DP. But if Pdat is absorbed into BE as in (iii), or into N as in (ii), the Experiencer DP must move up into Spec,IP and get a nominative Case there.

NOTES

1. Possibly (10) is also the configuration for Locatives, but we shall not argue this point here.

REFERENCES

Anandan, K.N. 1985. Predicate Nominals in English and Malayalam. M.Litt. dissertation, Central Institute of English & Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Hale, Ken, and Samuel Jay Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. In Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, eds., The View from Building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Freeze, R. 1992. Existentials and other locatives. Language 68:553-595.

Kayne, R. 1993. Toward a modular theory of auxiliary selection. Reprinted in R. Kayne, Parameters and Universals, Oxford University Press, New York, 2000 [pp. 107- 130].

Szabolcsi, A. 1983. The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review 3:89- 102.

HOME PAGE | BACK ISSUES | Preparing a Dictionary of Idioms in Indian Languages | Gown and Saree, Hand in Hand - A Review of Two English Readers for Indian Students | The Argument Structure of 'Dative Subject' Verbs | Linguistics Information in the Internet, With Special Reference to India | Urdu in Rajasthan | Sangeetha's Cookbook - Langue and Parole of Recipes - CHICKEN WITH HONEY LEMON SAUCE | CONTACT EDITOR

K. A. Jayaseelan, Ph.D.

Central Institute of English & Foreign Languages

Hyderabad 500 007, India

E-mail: jayamrit@eth.net.