AN APPEAL FOR SUPPORT

- We are in need of support to meet expenses relating to some new and essential software, formatting of articles and books, maintaining and running the journal through hosting, correrspondences, etc. If you wish to support this voluntary effort, please send your contributions to

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road Suite C

Bloomington

MN 55438, USA.

Also please use the AMAZON link to buy your books. Even the smallest contribution will go a long way in supporting this journal. Thank you. Thirumalai, Editor.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- A LINGUISTIC STUDY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM AT THE SECONDARY LEVEL IN BANGLADESH - A COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH TO CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT by

Kamrul Hasan, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION VIA EYE AND FACE in Indian Contexts by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION

VIA GESTURE: A STUDY OF INDIAN CONTEXTS by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - CIEFL Occasional

Papers in Linguistics,

Vol. 1 - Language, Thought

and Disorder - Some Classic Positions by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - English in India:

Loyalty and Attitudes

by Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education

by B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI

AND MALAYALAM

by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D. - LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS

IN TAMIL

by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D. - An Introduction to TESOL:

Methods of Teaching English

to Speakers of Other Languages

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Transformation of

Natural Language

into Indexing Language:

Kannada - A Case Study

by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. - How to Learn

Another Language?

by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Verbal Communication

with CP Children

by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D.

and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Bringing Order

to Linguistic Diversity

- Language Planning in

the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF LINGUISTIC RIGHTS

- Lord Macaulay and

His Minute on

Indian Education - In Defense of

Indian Vernaculars

Against

Lord Macaulay's Minute

By A Contemporary of

Lord Macaulay - Languages of India,

Census of India 1991 - The Constitution of India:

Provisions Relating to

Languages - The Official

Languages Act, 1963

(As Amended 1967) - Mother Tongues of India,

According to

1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- OCTOBER 2004 - INDEX OF AUTHORS

AND THEIR ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- OCTOBER 2004

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org, or send your floppy disk (preferably in Microsoft Word) by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road, Suite C.,

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA. - Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2004

M. S. Thirumalai

FIFTY YEARS OF LANGUAGE PLANNING FOR MODERN HINDI

The Official Language of India

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D.

1. ABSTRACT

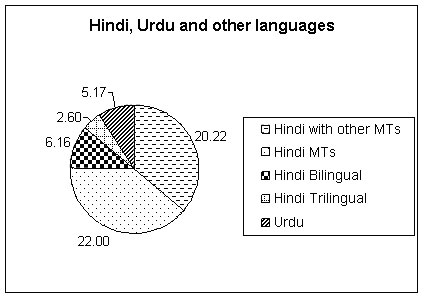

Hindi - according to the 1991 Census of India, is the mother tongue of 233,432,285 persons (22% of the entire Indian population), and is spoken as a language (which includes 47 or so mother tongues cobbled up under it) by 337,272,114 persons (42.22% of the entire Indian population). It is also used as a second language by another 6.16% of the population, and as a third language by yet another 2.60% by other language speakers. In total, in India, Hindi is known officially to 50.98% of Indians and, thus, has the status of the major language of the nation.

The adoption of the Indian Constitution in 1951 that accepted Hindi as the official language of the Indian Union radically changed the course of the development of Hindi. Hindi lacked even any standardization at that juncture. The history of Modern Hindi, thus, is the history of 50 years of planned development. As official language of the Union and several states, Hindi is used from the lowest unit of administration panchayat (village government) to the National Parliament, and has replaced English to a great extent. Now, Hindi is taught as a language in the domain of education. The Three Language Formula, adopted as an educational strategy to foster national integration in multilingual situations, has made Hindi a part and parcel of the educational system of the country. It is used as a major medium of instruction from the lowest level to the doctoral level, excluding technical education. It is extensively used in the mass media - print, television, cinema and defense services. It has absorbed the technological developments in the fields of printing and computer technology. It has web pages, and it can be used for search in search engines. This has made Hindi one of the richest languages of independent India and the world.

Today, though Hindi is not recognized as a national language, is the lingua franca of multilingual India, and it knits different mother tongue speakers together as the most important political constituency. This phenomenal change has been made possible due to the systematic status and corpus planning adopted and implemented by the Union and State governments through committees, institutions and well-meaning individuals, dedicated for the development of Hindi.

This paper traces, briefly, the history of the development of Hindi in two stages from 1900 to 1950, and from 1950 to 2003. Special attention is given to the varieties of legislation, mechanics of the implementation of the legislative provisions, relevant decisions of the various High Courts and the Supreme Court of India, the contribution of the globalization processes, problems with the linguistic structure and sociolinguistic functions, special characteristics of corpus of status planning as applied to Hindi, the response to such deep involvement in language planning by the government machinery from the native speakers of Hindi and non-Hindi States of the Union as well as the religious minorities of India and their impact on the language planning process, and the "peculiar" processes of developing a Hindi officialese, etc.

2. Introduction

Modern India is a multilingual nation. As per her 1961 count of the languages, India has more than 1650 mother tongues, belonging to genetically five different language families. They are rationalized into 216 mother tongues and grouped into 114 languages by the 1991 Census - Austro-Asiatic (14 languages with a total population of 1.13%), Dravidian (17 languages with a total population of 22.53%), Indo-European - Indo-Aryan (19 languages with the total population of 75.28%), and Germanic (1 language, with the total population of 0.02%), Semito-Harmitic (1 language, with the total population of 0.01%), and Tibeto-Burman (62 languages with the total population of 0.97%). A good number of languages recorded in the Indian Census could not be classified as to their genetic relation, and so are treated as Unclassified Languages. The Indo-Aryan languages are spoken by the maximum number of speakers, followed in the descending order by the Dravidian, Austro-Asiatic, and Sino-Tibetan (Tibeto-Burman) languages (Mallikarjun: 2004). Hindi belongs to the Indo-Aryan family of languages.

3. National/Official language(s) in India

The nation is one, and it is a concrete entity, but the perception of what constitutes a 'nation' differs from one speech community to another, from one political system to another, and from one point of time to another in the history. The perception voiced varies with the user of the term. Hence, it is possible for some of the users to interpret the concept 'nation' solely depending upon the situation that they face.

It was with deesha 'country' that people were more familiar than with 'raashtra' 'nation' in earlier times. The geographical territory ruled by a 'king' dominated this perception, in a way. The perception then was dependent on the authority with which one should ultimately communicate, for ultimate administrative purposes. KauTilya, in his artha shaastra identifies, "the king, the minister, the country, the fort, the treasury, the army and the friend, and the enemy … " as the elements of sovereignty. Tirukkural identifies the constituents of a state as "the king, troops, population, substance, council, alliances, and fortifications". The vastukoosha lists "the king, the minister, population, fort, treasure, friends and territory" as the constituents of the State.

The word 'nation' is derived from the Latin root to mean 'to be born.' It connotes a people of common descent. According to Josef Stalin, "A nation is a historically formed stable community of people which arose on the basis of common language, territory, economic life and psychological make up which has manifested in a common culture. That the language communities differ from one another in the perception of what a nation is." The concept is amply demonstrated in language use, rather in the changes that are necessitated in their use of terms.

Inclusive versus exclusive notions as in the case of Meitheis, Thaadous and Mizos dominate the concept of nation in some language communities. In some other communities, a progression from a smaller unit to a larger ultimate unit, geographic or otherwise, dominates the notion of nation (as in the case of the Malayalam speech community). A distinction between the crude and the polished, between the non-standard and the standard, actually dominates the evolution of 'nation' in some language communities. In several others, the concept of 'nation' is one of adjustment and allocation of meanings to existing words to account for the nation. In still others, the adjustment and allocation of meanings is made possible only by an adoption of words from other languages. In some languages, a new meaning of 'nation' is added to the only existing word, and a systematic ambiguity is established (Mallikarjun:1986).

The notion that there has to be a national language for a nation is the main reason for all the dialogues on the issue. The dialogue is made possible wherever there is more than one language used in a nation. When there is only one language used in a nation, there is actually no need to declare or recognize that language as the national language; the situation simply needs, not an official recognition in the Constitution, but an acceptance of it by the population of that nation. However, when more than one language is used in a nation, acceptance of one language as the national language of a nation requires the acceptance of that language as the national language by the speakers all the languages of that nation.

Highly heterogeneous linguistic situations with a democratic political system will normally not allow imposition of a language or languages as the national language or languages of that nation. India is a classic example of this condition. I consider it imperative that the notion of a national language should be in consonance with a nation, but an official language is one that is in consonance more with the administrative needs of a country.

It is a judicious and conscious decision of the founding fathers of the Constitution of India not to use the concept of "national language" (at least in the original which was drafted in English) in the Constitution and to opt for the word "official language of the Union". And hence, Hindi, or any other Indian language, was not named or declared as the national language. But the general public and interested politicians do use the notion of national language frequently. It is highly thoughtful that, in India's multilingual context, the notion of "official language" is more valid.

Today, though Hindi is not recognized as the national language, it is the lingua franca of multilingual India, and it knits different mother tongue speakers together as the most important political constituency. This change of status from being one of the dialects into the status of a dominant language that subsumes other dialects and even languages under it, has been made possible due to the systematic status, corpus and acquisition planning adopted and implemented by the Union and State governments through committees, institutions, and well-meaning individuals, dedicated to the development of Hindi.

4. Hindi - Nomenclature

Linguistic Survey of India by George Abraham Grierson that was concluded in the early part of the twentieth century and the Census of India since 1881, are the major and important sources of information on the linguistic composition of the nation. Since 1881, details of 'mother tongue', 'language,' etc. regarding the people of India are being elicited and recorded. Especially the nomenclature under which the details 'Hindi' are recorded is also very important. This documentation has played a very important role in the life of Hindi and in the life of India.

While recording the names of languages, dialects, mother tongues etc., Grierson says that "…dialect names have been taken from the indigenous nomenclature, nearly all the language-names have had to be invented by Europeans. Some of them, such as 'Bengali,' 'Assamese,' and the like, are founded on words which have received English citizenship, and are not real Indian words at all; while others, like 'Hindustani,' Bihari, and so forth, are based on already existing Indian names of countries or nationalities" (Grierson 1901). When we come to the name of the language Hindi itself, Grierson writes that it is "…popularly applied to all the various Aryan languages spoken between the Punjab on the west and the river Mahaananda on the east; and between the Himalayas on the north and the river Narbada on the south." (Grierson: 1901)

Linguistic Survey of India speaks eloquently about Hindustani as an important dialect and a 'lingua franca of the greater part of India, spoken and understood over the whole of the Indian Peninsula'. At that time, 'Literary Hindustani, was used by both Hindus educated in Hindu tradition and Musalmans educated in Musalman system of education. The Hindus used Nagari script and Musalmans used Persion script to write the same language. This Hindustani included local vernacular, Literary Hindustani (including Urdu and Hindi) and Dakhini.

The 1911 Census of India considers 'Hindi' as 'a comprehensive word which includes at least three distinct languages, Western Hindi, Eastern Hindi and Bihari'. Hindustani which was a major component of Hindi and part of the Constitution of India played an important role in the movement for the independence of India as a link language. Unfortunately, the same has vanished from the linguistic demography of India in the records and publications of the 1991 Census!

5. Hindi - Demography

The present day nomenclature/term of Hindi language includes 49 mother tongues, creating a statistical majority. It is amazing to see how the statistical majority of Hindi speakers is achieved. Different mother tongues are combined to make a linguistic majority. If this kind of clustering is not done, the linguistic demography of Hindi will be different. It is the mother tongue of 22% of the population; it has 20.22% of mother tongues clustered under it as a language. It is used as a second language by 6.16%, and as a third language by 2.60%, totaling to 50.98% of the entire population of India. Hindi crosses the magic figure of the definition of majority, a language with more than 50% of the population of India, in the 1991 Census.

Hindi is mainly a rural language with 78.61% of its speakers residing in the rural areas, and only 21.39% of Hindi speakers are urbanites.

If we take communicability of Hindi in India as the sole criterion, we have to take into consideration that Urdu and Hindi are mutually intelligible speech forms for centuries together and they have a common core of phonology, syntax, and a major vocabulary share. They are separated only by two script forms and of late, since a century or so, by two religions. There were times when the religion was not in picture as a separator. Technological developments make script a minor issue due to easy convertibility of a language from one script to another script. Hence I am inclined to take Indian Urdu and Hindi together as one entity for all communicative purposes and add the statistics of Urdu speakers to Hindi itself. In that case Hindi is communicable to 56.15% of the population of the country.

Here, I would like to point out that the Statistical Hand Book (as interpreted by the Radhakrishnan Commission) presented to the Constituent Assembly (which debated various provisions that govern the country including the issue of language in 1947), showed that Hindi had four parts: Eastern Hindi: 7,867,103 persons with Awadhi, Maithili, Magadhi, Bhojpuri; Western Hindi: 71,354,504 persons with Urdu, Braj Bhasha; Bihari : 27,926,502 persons, and Rajasthani: 13,897,508 persons. It may thus be observed here that Urdu was considered a part of Hindi. The report also had observed that "Hindi is the language of minority, although a large minority. Unfortunately it does not possess any advantages - literary or historical, over the other modern Indian languages."

6. Hindi - Multilingualism

There are two dimensions to the situation - Hindi speakers being multilingual in other languages, and other language speakers being multilingual in Hindi. The rate of bilingualism and trilingualism in the country is on the increase from decade to decade. The same was in 1961- 9.70%, in 1971- 3.04%, in 1981-13.34% and in 1991-19.44%.

However, speakers of Hindi are least bilingual (11.01%), and least trilingual (2.98%) in any other language(s). Their bilingual and trilingual profile, thus, is far below the national average of 19.44%. However one finds an increase of bilingualism among Hindi speakers in 1981 from 4.76% to 11.01% in 1991.

But, among other language speakers, Hindi has spread substantially. The following statistics of the 1991 Census for the bilingual and trilingual speakers clearly reveal this situation.

Multilingualism of Major Indian Language Speakers in Hindi

|

Language Multilingualism Bilingualism Trilingualism |

|

1. Kashmiri 52.52 42.16 10.36 |

|

2. Sindhi 50.61 40.74 09.91 |

|

3. Punjabi 36.25 30.75 05.50 |

|

4. Nepali 35.46 23.25 12.21 |

|

5. Marathi 25.79 23.79 02.00 |

|

6. Konkani 24.75 08.58 16.47 |

|

7. Manipuri 24.31 10.02 14.29 |

|

8. Gujarati 23.95 22.13 01.78 |

|

9. Urdu 20.61 16.60 04.01 |

|

10. Malayalam 19.07 02.69 16.38 |

|

11. Assamese 16.93 08.82 08.11 |

|

12. Oriya 11.36 04.56 11.36 |

|

13. Telugu 08.01 03.28 04.73 |

|

14. Kannada 08.98 03.89 05.09 |

|

15. Bengali 06.64 03.99 02.65 |

|

16. Tamil 01.56 00.70 00.86 |

Multilingualism among other minor languages is widespread and normally it is in the language of the State or the Union territory where their speakers mainly reside.

7. Hindi - Policy, Planning and Implementation

Language policy is seen as: "1. What government does officially-through legislation, court decisions, executive action, or other means-to(a)determine how languages are used in public contexts, (b) cultivate language skills needed to meet national priorities, or establish the rights of individuals or groups to learn, use, and maintain languages. 2. Government regulation of its own language use, including steps to facilitate clear communication, train and recruit personnel, guarantee due process, foster political participation, and provide access to public services, proceedings, and documents" (Crawford J :2000).

Whereas language planning can be for documentation, maintenance and/or for development. Among all the mother tongues, dialects and languages, Hindi is at the center stage of language planning initiatives. Language planning relating to the status, corpus and acquisition for Indian languages including Hindi began long before her independence.

The main focus of post-independence India's language planning relating to Hindi is to (a) encourage and take necessary steps for the maintenance of plurilingual nature of the country, (b) develop Hindi as the official language and (c) help in evolving Hindi as the lingua franca. The 1920 resolution of the Indian National Congress set the ball in motion, which culminated in including Hindi as the official language of the Union in the Constitution of India. As a follow up of this decision and movement, many other States and Union Territories too declared Hindi as their official language.

Four stages in the process of language planning relating to it could be identified. These are:

| First stage | Formative days of planning before independence: Census of 1901 onwards. [Period to get a status] |

| Second stage | Constitutional Assembly Debates which assigned some status to major Indian languages, including Hindi. since 1950. [Period to restrict and replace English] |

| Third stage | Redefining the role of Hindi in the context of the anti-Hindi riots: From the Parliamentary resolution of 1968. [Period of progressive use and spread of Hindi] |

| Fourth stage | Globalization and its impact on the role and functioning of Hindi: Since 1992. [Period to retain the gains of the past] |

8. Modern Hindi

In the history of Indian languages, Hindi is one of the languages which was not an official language, or language of administration of any dynasty, unlike other languages such as Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, etc. The officially identified Hindi of today as we already saw is an umbrella term/form to cover a composite speech form, formed out of different but possibly mutually intelligible mother tongues. It is a super-ordinate term, subsuming a bunch of subordinate mother tongues/dialects. Thus, the present Hindi is the result of the planned development of independent India.

The common core of linguistic features that exist between different mother tongues grouped under the language Hindi and the areal features seem to be helping smooth communication and unhindered interaction among the speakers of these mother tongues. Hindi as a form of language started to knit India - a multilingual nation, for the last one hundred years, as part of the process of struggle for independence, and it has assumed this role more forcefully in the last fifty years of language planning. First it integrated submerging different mother tongue/dialect/language identities as an umbrella language; then it penetrated into the sphere of other Indo-Aryan language speaking areas due to linguistic affinity and geographic contiguity and thirdly into the territories of the speakers of other language families due to acquisition planning. It is integrating Indians communicatively and, may, in due course of time, socially and economically too.

Modern Hindi is this form of language which has evolved into an almost wholly acceptable form in India after her independence and is in use in different domains. Three distinct forms of Hindi have evolved and they perform three different kinds of functions.

The first one is used in formal contexts as standard Hindi, both in spoken and written forms; the second one is the official or administrative Hindi, which is used in a limited but important domain of administration, and the third form is lingua-franca Hindi, which is used in non-formal contexts across the country in spoken form only, overlaid by the shadow of the regional languages wherever it is used. This form is more akin to Mahatma Gandhi's notion of Hindustani, also now popularly known as bazaar Hindi. This kind of Hindi is used across different language speakers for intra-group communication in the country.

Though, in one way, it could be considered as a part of official or administrative Hindi, the Hindi used in the defense services is the best example of development of Hindi as a very successful tool for communication among the speakers belonging to various mother tongue groups and different official hierarchies. This Hindi of armed forces, which could be named as 'fouji Hindi,' exhibits the strength of official Hindi and lingua franca Hindi. English has remained as a language of elites due to the process of adopting it only for administration and higher education and not for popular communication. Now, due to the process of globalization, people aspire to learn it, whereas due to mobility, communication network, and expansion and availability of modern technologies, Modern Hindi has become the language of masses to a large extent.

9. Hindi - Status

When the official language status was granted to Hindi, only the state of Rajasthan had some tradition of using Hindi for a few official purposes. Soon after independence, some of the states, where Hindi was a major language, officially took steps to use Hindi in administration. Uttar Pradesh declared Hindi in Devanagari script as the official language of the state on October 8, 1947, and, in the same month, notified that Hindi be used in civil and criminal courts. Similarly, Bihar, on June 4, 1948, adopted Hindi as its official language, and on June 26, 1948 declared it as language of the court.

Once the Constitution of India came into force on January 26, 1950, the status of Hindi was greatly enhanced. It is Hindi in Devanagari script and the international form of Indian numerals form the Official language of the Union. Among the Indian languages, Hindi is the most highly empowered language which constitutionally/legally has multiple status - an official language of the Union; official language of 13 states and union territories; the major regional language in 9 states where it is a majority language, and an important minority language in 18 states and union territories. Also it is a language of deliberations of the Parliament of India and state legislatures in the states in which it is recognized as an official language. Apart from this, the Constitution also provides that, with mutual consent, any two states or the states and the Union can use it as a language for their inter- communication. It is the majority language of the country and also a Scheduled Language since it is in the VIIIth Schedule of the Constitution. It is the only language about whose development the Constitution has given direction, and hence it has the constitutional right for development.

It has to be remembered that when Hindi got the status described above, English was in use in most or all domains. English was allowed to be continued due to its 'international' nature as a 'neutral language' in multilingual situations supposed to be providing equal space for all languages. So, use of English was allowed to be continued for a period of fifteen years in all such domains in which it was in use prior to January 26, 1950. During this interim period, Hindi was allowed to equip itself to replace English. After this interim period of preparation, switch over from English to Hindi was scheduled to take its place. (The official language rules it may please be noted here, are applicable to all states and union territories other than Tamil Nadu.)

Language planning aimed at developing Hindi as an official language, not as a national language. Implementing was not an easy task. The switch over was to take place almost from scratch. The implementation mechanism for Hindi to become an official language was and is through the formation of Commissions, Parliamentary Committees, Parliament Resolutions, Acts, Rules, Official Orders, etc., and, above all, through consensus. The important feature in this process was and is one of embedding the structure of implementation into the Constitution.

Commission: After five years of the commencement of the Constitution a Commission with a Chairperson (B. G. Kher) and members representing the different languages listed in the Eighth Schedule was appointed. Some of the important objectives set before this commission were to make recommendations on: (a) the progressive use of the Hindi language for the official purposes of the Union; (b) identifying the restrictions imposed on the use of the English language for all or any of the official purposes of the Union; (c) language to be used for all or any of the judicial purposes; (d) form of numerals to be used for any one or more specified purposes of the Union; (e) language for communication between the Union and a State, or between one State and another and their use. The most important direction given to the commission for making recommendations was that it should "… have due regard to the industrial, cultural and scientific advancement of India, and the just claims and the interests of persons belonging to the non-Hindi speaking areas in regard to the public services." Thus, nation building became an integral and essential part of language development.

Materials: The Commission considered the 'preparation and standardization of the necessary special terminology', 'translation of rules, regulations, manuals, handbooks and other procedural literature' into Hindi as pre-requisites of a change over (from English to Hindi). And while doing such a translation, it advised for 'a measure of uniformity in the translations of this procedural literature'.

Human resources: In the government, the employees' linguistic ability that was aimed in Hindi was equal to that of English as demonstrated in the 'qualification for purposes of recruitment to various categories'. However, "during earlier stages perhaps a slightly lower standard might suffice". For the employees who were 45 in age and above, 'comprehending knowledge' of Hindi and not 'high levels of linguistic ability for purposes of expression corresponding to the levels of their ability in English' was recommended. Also, the Commission recommended that the "Government (to) impose ... obligatory requirements on Government servants to qualify themselves in Hindi within a reasonable period to the extent requisite for the discharge of their duties."

Relation with regional languages: For all India administrative agencies such as Railways, Posts and Telegraphs, Excise, Customs, Tax Departments, 'with a view to the convenience of the public,' what the Commission recommended was "a measure of permanent bilingualism. That is 'they will use the Hindi language for purposes of internal working and respective regional languages in their public dealings in the respective regions". Also, in case of India Audit and Accounts Department, in the light of the States adopting the concerned regional language as the Official Language, the Commission recommended 'to arrange that the staff of the Indian Audit and Accounts Department dealing with the affairs of the States is versed in that language sufficiently for the purpose of carrying out its duties of compiling and the exercise of audit'. Hence the Accountant General's Office in a State "should be capable of compiling accounts returns submitted in the regional language and conducting audit with reference to noting and administrative language."

Legislation: The Commission made a distinction "between the language to be accepted for the proceedings and deliberations of legislative bodies and the language of the enactments which they legislate depending upon their functionality." Since eventually authoritative enactment ought to be in Hindi in both Parliament and State legislations, the Commission recommended for the sake of public convenience publication of translations "of the enactments in different regional languages. In respect of State Legislation, this would be normally necessary with regional language(s) prevalent in the State, whereas in respect of Parliamentary legislation it may be necessary in all the important regional languages current in the country". Finally, when the total change over from English to Hindi is implemented "the language of legislation and also of course consequently the language of all statutory orders, rules, etc., issued under only law, should be in the Hindi language."

For smooth transition from English to Hindi, a bilingual model was adopted. Translation of texts from English to Hindi was chosen as the first mode of creation of material resources like administrative manuals, rule books, acts, bilingual glossaries, etc.

Committee of the Parliament on Official languages: After ten years with a Chairperson (G. B. Pant) and thirty members, "of whom twenty shall be members of the House of the People and ten shall be members of the Council of States to be elected respectively" was constituted to examine the recommendations of the Commission and report their opinion to the President. This is the mechanism inbuilt into the system and is helping in implementation of the Constitutional provisions.

The Official Languages Act 1963 was amended subsequently. After fifteen years of the Constitution coming into existence due to political social and linguistic exigencies, the switch over from English to Hindi did not take place. But, through amendment to the Official Languages Act, English was allowed / permitted to be used for all official purposes of the Union and for the transaction of business in parliament. So, Hindi in Devanagari script is the Official Language of the Union. But English language, in addition to Hindi Language, may also be used for Official purposes of the Union.

Authorized Hindi translation of Central Acts, Ordinance, order, rule, regulation, etc., issued under the Constitution or under any Central Act is taken as authoritative text in Hindi. Similarly, the authoritative text in the English language of all Bills to be introduced, or amendments to be moved in either House of the Parliament shall be accompanied by a translation of the same in Hindi. Thus, permanent Hindi - English bilingualism was accepted and introduced. While doing so " …due consideration shall be given to the quick and efficient disposal of the official business and the interests of the general public and in particular, the rules so made shall ensure that persons serving in connection with the affairs of the Union and having proficiency either in Hindi or in the English language may function effectively and that they are not placed at a disadvantage on the ground that they do not have proficiency in both the languages."

The Official Language Resolution, 1968: Resolved for growth or development of Hindi to take place concurrently with that of other major Indian languages, " … in the interest of the educational and cultural advancement of the country … alongside Hindi so that they grow rapidly in richness and become effective means of communicating modern knowledge." At the same time, other Indian languages were not left out.

This shows that in multilingual situations, all languages play an important role in nation building and they all need space for their survival and growth. So far, we saw the way in which the Indian social and political setup has allowed Hindi to create space for its growth without forcing out other languages from their own space, and thus maintaining harmony. It has become an additional language and not a substitute language.

10. Hindi - Strategies for progressive use and spread:

Since the goal was to usher in an all round development of Hindi, three distinct Ministries of the Government of India are directly involved in the implementation of the national consensus. They are the Department of Education now in the Ministry of HRD, Ministry of Home Affairs, and the Ministry of Law. The users of Hindi include: Ministries/departments, attached and subordinate offices, public sector undertakings, corporations, banks, commissions, tribunals, companies owned or controlled by the government and financial institutions, etc.

- Creating appropriate geographical space: The Reorganization of Indian states on linguistic lines in 1956 created a division called Hindi-speaking states and Non-Hindi speaking states. Different states have different linguistic composition. Uniform strategies do not help in the use of Hindi as official language. Hence, the country, for this purpose, is divided into to three regions as per the Official Language Rules. Region A - Bihar, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh; Region B - Gujarat, Maharashtra, Punjab, UTs of A&N Islands, Chandigarh; Region C - other than those listed in A & B; Each region will have different kinds of programmes for the successful implementation of the official language policy of the government.

- Creating appropriate physical space: Papers to be tabled in the parliament, publication of statutory rules, authorized Central Act, Rules, Regulations, treaties and agreements, annual and other regular reports, magazines and journals, statistical hand books will be both in Hindi and English.

- Creating visibility: One of the major factors for any language and script is its visibility in public space. Across the country, in the railway stations, airports, milestones, sign boards, name plates, letter heads of the Union government offices, rubber stamps, office seals, name plates on staff cars, invitations issued on different occasions, etc., Hindi is used, and a variety of forms used by the public for different purposes are all made available in bilingual or multilingual formats.

- Creating a simple form of Hindi: The Hindi to be used in official work is expected to be simple and not complex. It should be easy to understand. The words commonly understood should be used frequently and all communications need not hesitate to use the popular words from other languages. For difficult Hindi words, the English word can be given in parenthesis. Artificial translation from English should be avoided. First draft of any communication itself should be done in Hindi and the officials should avoid doing it in English and then attempting to translate the English text into Hindi. The syntax of Hindi should confirm to its genius. To maintain standards, the administrative, scientific and technical terminology should be used from the glossaries prepared by the Commission for Scientific and Technical Terminology and for legal affairs from the glossaries of the legislative department of the Ministry of Law.

- Creating material resource: When Hindi was declared Official Language, it needed standardized bi-lingual, multi-lingual glossaries, procedural manuals, codes, registers that needed to produce orders, notices, texts of bills and acts, and Hindi translation of non-statutory procedural literature. Gradually, in due course of time all types of forms and other materials were made available and supplied free of cost to offices and officials.

- Creating human resource: The human resource involved in use of official Hindi belonged to two categories. The first group had knowledge of the language, since Hindi was their mother tongue/language with which they had acquaintance. The second group had neither. The first group was trained in the ways in which it has to use Hindi in the new context, and the second group was trained from scratch. The training materials and manuals were created and people were trained using both face to face and distance mode. This training included refresher training. Additionally, a large number of translators were trained through in-service training programmes to undertake translation work. Thus, attempts to impart working knowledge/proficiency to the officials in Hindi were made.

- Creating technical resources: The typewriter, stenographers, typists, machines for writing addresses, bilingual electronic machines earlier, and now, the software with Hindi in Devanagari fonts and UNICODE encoding, is made available in Hindi, even before such resources are made available in any other language. And the human resources for using all this technical resource is created either on the job training, or through training before entry into service. Also it is one of the four Indian languages through which one can search the internet.

- Creating awareness: It is done in many ways. September 14 of every year is celebrated as Rajbhasha Day, that week as Rajbhasha saptaah and the month as Rajbhasha mahiina. In addition to this, most part of the year the offices and the Institutions keep organizing various kinds of programmes relating to Rajbhasha to create awareness among their own employees and the citizens.

- Creating overseeing mechanisms: There is a system of inspection, and the inspection committees do it. They are called Official Language Implementation Committees. The mechanism to oversee the implementation of the progressive use of Hindi begins from the office/institution itself with the Head of the Department/office ensuring that the provisions are properly complied. The Head devises suitable check points for this. Each office has a committee to oversee the implementation. Each town has a Town Official Language Implementation Committee. These oversee, share, debate about the difficulties faced in implementation, and consolidates the work going on in official Hindi. Each Ministry has a mechanism to monitor at its level and, ultimately, it is the Official Language wing of the Ministry of Home Affairs that coordinates at the national level all the activities of Rajbhasha.

- Creating incentives: At every level, there are awards for the individual users of official Hindi and the offices/institutions, subordinate offices, ministries, etc. Awards are given for writing original books on scientific and technical subjects in Hindi. In addition to these awards, the stenographers and typists are given an incentive allowance for doing their official work in Hindi in addition to English.

11. Hindi - Corpus

When a language has to be used in new domains, or in old domains with newer emphasis and nuances, there arises a need to develop additional vocabulary, or new vocabulary and new styles of expression. The planning for the development of technical vocabulary in Indian languages began in 1830 by the Translation Society of old Delhi college. The Educational System of 1943 reports three schools of thought in this regard:

(i) wholesale adoption of English terminology in all scientific writings in all Indian languages; (ii) inclusion of a limited vocabulary of basic and internationally accepted words and expressions in their English forms, and the use with fresh coining if necessary, of suitable equivalents in the various languages; and (iii) with the exception of recognized international nomenclature and notation (as in chemistry or botany), the adoption of entirely indigenous systems of terminology, which may be two or three in number, dividing the Indian languages into two or three groups, such as Indo-Aryan and Dravidian; or Sanskritic Perso-Arabic and Dravidian.

Hindi acquired a new status in independent India. This led to the beginning of several language development activities regarding Hindi. The problems faced by Hindi at this stage in its career as a language of wider communication were different from those of other Indian languages. Pan Indian-ness and its acceptability across the country was one of the important considerations. As I already said, Hindi could not claim to be official language with a long history. No acceptable standard form was in currency. In 1949 it was considered as an undeveloped, inadequate language: "…it possesses little scientific literature and its technical vocabulary is rudimentary" (Radhakrishnan Commission 1949).

In order to overcome this, three broad principles were suggested by the Commission (i) Assimilation - borrow and adopt words without violence to the genius of the language like English. (ii) Inclusiveness - retaining the words which have already entered the language. (iii) Non-Exclusiveness - relaying only on one language to borrow. All these three were recommended. And it was also predicted that, "When Hindi assimilates the terms in popular usage and adopts scientific and technical terms which are used internationally, it will grow richer and fuller than it is today …"

In order to fit into new circumstances as the official language of India, for its use in and communicating science and technology, and for its use as a lingua franca across the country, corpus planning activity was undertaken. The direction for this planning came from the Constitution itself. The Article 351 elucidates as to 'who' (union government) 'how' (assimilating), and 'why' (spread) it should be done. Accordingly it is the duty of the Union - to develop; enrich by assimilating the forms, style and expressions used in Hindustani and in the other languages specified in the Eighth Schedule; and by drawing, wherever necessary or desirable, for its vocabulary, primarily on Sanskrit and secondarily on other languages; promote the spread, so that it may serve as a medium of expression for all the elements of the composite culture of India. This article seems to assume that the product - Hindi to be an amalgamation of features of many major Indian languages. Evolving pan-Indian terminology was considered as an important objective.

With this direction standard Hindi terminology for administration, science, and technology were created by Committees and these were sought to be used in government correspondences, etc. In order to develop the needed technical terms and to ensure their use, the Committees and the government machinery formulated the principles that governed such creation and usage. They are: (a) 'International terms' should be adopted in their current English forms, as far as possible, and transliterated in Hindi and other Indian languages according to their genius. (b)The symbols will remain in international form written script, but abbreviations may be written in Nagari and standardized form, specially for common weights and measures, e.g. the symbol 'cm' for centimeter will be used as such in Hindi, but the abbreviation in Nagari may be (different, difficult to reproduce here -- Mallikarjun). This will apply to books for children and other popular works only, but in standard works of science and technology, the international symbols only, like cm., should be used. (c) Letters of Indian scripts may be used in geometrical figures (difficult to reproduce here -- Mallikarjun) but only letters of Roman and Greek alphabets should be used in trigonometrical relations e.g., sin A, cos B etc (d) Conceptual terms should generally be translated. (e) In the selection of Hindi equivalents simplicity, precision of meaning and easy intelligibility should be borne in mind. (f) Obscurantism and purism may be avoided. (g) The aim should be to achieve maximum possible identity in all Indian languages by selecting terms: common to as many of the regional languages as possible, and based on Sanskrit roots. (h) Indigenous terms, which have come into vogue in our languages for certain technical words of common use should be retained. (i) Such loan words from English, Portuguese, French, etc., as have gained wide currency in Indian languages should be retained e.g., ticket, signal, pension, police, bureau, restaurant, deluxe etc. (j) Transliteration of International terms into Devanagari Script-The transliteration of English terms should not be made so complex as to necessitate the introduction of new signs and symbols in the present Devanagari characters. The Devanagari rendering of English terms should aim at maximum approximation to the standard English pronunciation with such modifications as prevalent amongst the educated circle in India. (k)Gender - The International terms adopted in Hindi should be used in the masculine gender, unless there are compelling reasons to the contrary etc..

12. Hindi - Acquisition

A multi-ethnic and multi-lingual pluralistic nation needs to evolve education and language policies in such a way that all the segments that constitute the nation develop a sense of participation in the progress of governance and nation-building. In addition, the specific aspirations of the individual segments of the nation need to be met to the satisfaction of the various ethnic, religious, and linguistic communities. India's Freedom Struggle was not merely a struggle for independence; it also laid the groundwork for nation building even when the people were under the foreign yoke. Indian leaders did not postpone nation-building processes until India got freedom. The resolutions passed in the various conferences conducted by the Indian National Congress reveal that the national leadership, while waging their battle against the British rule, thought well ahead of time and equipped the nation with advance steps in the fields of education and language policies.

The Constitution of India makes provision for ' ... free and compulsory education for all children until they complete the age of fourteen years'. But the Constitution has no explicit statements regarding the language(s) to be taught in education or the language(s) through which education has to be imparted (except in the case of linguistic minorities). This may have been a tactical compromise or declaration on the part of the Constitution makers, because every one could sense the great linguistic complexity of free and democratic India. They left it to various committees and conferences to evolve suitable acquisition planning in due course of time. This has paid rich dividends. (Mallikarjun: 2001)

Hence, flexibility and liberality are the hall marks of language acquisition planning in India. It aims to (a) maintain pluralistic nature of the nation, (b) preserve the mother tongues of the children through their study as a subject in the school system, and (c) encourages the spread of Hindi among non-Hindi speaking population by making it a part of the educational system across the country and for all the school-going children.

In post-independence India, the first attempt to look at language in education was made by the University Education Commission (1949) popularly known as the Radhakrishnan Commission. This commission recommended that "(i) pupils at the higher secondary and University stages be made conversant with three languages - the regional language, the Federal language, and English, and (ii) Higher education be imparted through the instrumentality of the regional language with the option to use the Federal language as the medium of instruction either for some subjects or for all subjects." At that juncture the name of the Federal language referred to in this formulation was still to be decided and later it happened to be Hindi in due course of time.

Next comes the Secondary Education Commission (1952). At the Secondary state it also recommended for (i) Mother tongue, (ii) Regional language, (iii) the link language, that is, Hindi, and (iv) one classical language - Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, Arabic or Persian. The Central Advisory Board of Education (1957) reviewed the educational scene and recommended the implementation of the popularly known Three Language Formula (TLF). The exact formulation of the TLF by the Government of India that was arrived at in the meeting of Chief Ministers of States and Central Ministers (1961) is: (i) The regional language and the mother tongue when the latter is different from the regional language, (ii) Hindi, or, in Hindi speaking areas, another Indian language; and (iii) English or any other modern European language. Subsequently a modified or graduated TLF was proposed by the Education Commission, popularly known as the Kothari Commission (1964-66): (i) the mother tongue or the regional language; (ii) the official language of the Union, or the associate official language of the Union so long as it exists; and (iii) a modern Indian or Foreign language, not covered under (a) and (b) and other than the one used as the medium of instruction.

The Resolution of the Government of India on the Report of the Education Commission under The National Policy on Education (1968) states that, at the secondary stage, the State Governments should adopt, and vigorously implement, the three-language formula which includes the study of a modern Indian language, preferably one of the southern languages, apart from Hindi and English in the Hindi-speaking States, and of Hindi and English in the non-Hindi-speaking States. Suitable courses in Hindi and/or English should also be available in the universities and colleges with a view to improving the proficiency of students in these languages up to the prescribed university standards."

The Curriculum for the Ten Year School: A Framework of the NCERT (1975) suggests that "The first language should usually be the mother tongue. The second language should be Hindi wherever it is not the mother tongue. The third language should usually be English, but could be any other language. Sanskrit or Persian could be introduced as a part of the first or second language or introduced separately as a further subject." This was reiterated in the Education Policy (1986) and was adopted as the Programme of Action by the Parliament (1992). The National Curriculum Framework for School Education (2000) puts forth the simple form of the TLF thus: (i) the home language/the regional language, (ii) English, and (iii) Hindi in non-Hindi speaking states and any other modern Indian language in Hindi speaking states.

These are the major attempts to arrive at a language policy for education and this is how the TLF has evolved into its present day version. In all its versions, Hindi remained as one of the languages in the formula. The changes have taken place only in the case of other two languages of the scheme. Since education is in the concurrent list of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution of India, the language policy formulation for education and its implementation is left to the State governments under the Constitutional safeguards and broad guidelines of the TLF cited above.

This formula which was arrived at as the consensus among the speakers of different languages as a strategy for language education so far designated as a strategy had no legal status and was totally dependent on the governmental and institutional support but now it received a legal status through a decision of the Karnataka High Court judgment. According to this decision, the government is at liberty: "(a) to introduce Kannada as one of the two languages from that primary school class from which study of another language in addition to mother-tongue is made obligatory as part of general pattern of primary education; and (b) to make study of Kannada compulsory as one of the three languages for study in secondary schools, by making appropriate order or Rules, and make it applicable to all those whose mother-tongue is Kannada and also to linguistic minorities who are and who become permanent residents of this State, in all primary and secondary schools respectively, whether they are Government or Government recognized, including those established by any of the linguistic minorities".

Now, as shown in the Table prepared on the basis of the information available in the year 2000, Hindi has become an integral part of language education in India, apart from English in all the states and union territories as one of the three languages (except in the state of Tamil Nadu. The people of Tamil Nadu have chosen non-formal modes to acquire knowledge of Hindi even before India got independence, and they continue to do so even now). According to the Sixth All India Educational Survey, about 82% of schools upper at the primary stage, 35.97% at the upper primary stage and 28.50% at the secondary stage teach Hindi as first language. The Fifth All India Educational Survey informs that Hindi is medium of instruction in 41.35% of schools at the primary stage, 38.60% at the upper primary stage and 31.43% at the secondary schools. The 38th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India for the period July 1999 to June 2000 reports that Hindi is taught as the First language in 15, Second language in 12, and Third language in 17 states and union territories.

The modus operandi adopted to implement the use of Hindi in education follows the principle of decentralization. The teachers teaching Hindi in the schools are either mother tongue speakers teaching it as mother tongue, or those who have learnt it as a language in their schooling and teach it as a second or third language. The preparation of Hindi textbooks is also decentralized. Each state normally prepares the text books needed for its schools. These Hindi text books used in a particular state are produced keeping in view the culture, art, architecture, physical and natural environments, etc., of the concerned state or union territory and students' specific needs.

There is a direct relationship between language(s) used in education, and language or languages used in administration. Unlike the previous generation of students who were unequipped to handle Hindi in official contexts, the present generation of students possesses some minimum knowledge of Hindi that helps them to use Hindi in official contexts. Thus, Hindi has knit the multilingual India together by becoming an obligatory part of language education and by slowly increasing the need for its use various domains of language use in India. This further makes it necessary for individuals to learn Hindi on their own accord.

13. Mass Media and Widening of Horizon of Hindi

Over and above all the official intervention for the progressive use and spread of Hindi, the media is also involved in the implementation of the language policy. Non-Hindi speakers in India are like passive smokers of Hindi. Impact of media like television, radio and films is enormous. During the year 2000 India produced 855 feature films. Majority of them were in Hindi and only Hindi films have market through out India. Viewers do not have language boundaries. Other language films have very limited market, they hardly have viewers outside their language boundaries. Similarly at the end of the year 2003 about 77 television channels were beaming their programmes and only Hindi channels have viewers through out the country.

The table given below will give a Glimpse of growth of Hindi print media in the country.

|

Year |

Dailies |

Total Periodicals |

|

1972 |

225 |

2694 |

|

1981 |

409 |

5329 |

|

1996 |

2004 |

15647 |

|

1999 |

2305 |

18903 |

|

2000 |

2393 |

19685 |

|

2001 |

2507 |

20589 |

|

2002 |

3410 |

22067 |

|

Rank |

Name of the Publication |

Readership (in 'lakhs) |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

Dainik Bhaskar (Hindi) Dainik Jagran (Hindi) Daily Thanthi (Tamil) Eenadu (Telugu). Malayala Manorama Malayalam) Amar Ujala (Hindi) Hindustan (Hindi) Lokmat (Marathi) Mathrubhumi (Malayalam) Times of India (English) |

157.09' 149.85 100.94 094.58 087.98 086.40 078.99 078.67 076.46 074.19

|

Top ten magazines 2003

It may be noted that Hindi tops in both categories

14. Globalization and Hindi

The concept of globalization entered the Indian planning process in April 1992 and since then it has brought a sea of changes in society, and economy. Globalization has made positive as well as negative impact on all Indian languages including Hindi. The positive impact is that, due to the expansion of media network in the past decade, pan-Indian Hindi is developing mainly through the audio-visual mass media. The Hindi thus developed has a greater impact on non-Hindi speaking states. This could lead to a position where pan-Indian Hindi assumes some of the functions of non-Hindi major Indian languages. A secondary globalization process, thus, helps Hindi, and may not help the other major Indian languages. The negative impact is that the developments that have taken place in the area of its use in administration are backtracking due to its inability to cope up with technological developments. In the domain of education, the demand for English is on the rise. (Mallikarjun 2003).

15. Conclusions

- Nation building in a multilingual society is the responsibility of all languages and their speakers and not a monopoly of one or a few languages. Here each language needs to behave in an accommodative spirit and create space for survival and growth and the development of all other languages through a policy of accommodation. In this Indian context, Hindi has become an additional language and not a substitute language for speakers of other languages.

- It is obvious that during the last fifty years Hindi has made tremendous progress as an Official language of the country. It is accepted as an official language in many states. It has a very important place in the school curriculum all over India. Now, it is learned by more people. It is rich with elaborate terminology, although there is still some confusion relating to the standardization of these terms and their usage. Government, through various means, helps spread of the language and enables its use as an official language. Technology helps the spread and use of it in many ways. Radio, Television, and the movies offer excellent opportunities for this language to become more popular in India among all linguistic groups.

- The problems faced by a multilingual nation to settle upon a single language or a few languages as the official languages of the nation are quite different from the problems faced by the nations which have a clear dominant language of their own.

- In such nations, the governments are more concerned with equipping their national languages as fit vehicles for governance and education in consonance with their modern needs.

- On the other hand, in multilingual nations such as India, the very acceptance of any one language as the official language is questioned, and the question of official language or languages always creates social and political problems, sometimes very difficult to solve.

- In addition, these official languages have to be developed as fit vehicles for governance and education to take care of the modern needs.

- Thirdly, democracy insists upon even handedness between various groups, especially when such groups acquire bargaining powers through political developments (similar to what we notice in India for the last 10 years or so), thus necessitating support for other languages used in the country.

So far, despite several serious linguistic agitations against the acceptance and development of Hindi as the official language of India, Hindi is spreading out and is receiving acceptance in many domains of governance and education.

- The greatest threat to Hindi as an official language or the official language comes from the processes of globalization. It appears that the people of India, both Hindi-speaking and non-Hindi speaking populations, may opt for an interesting role for Hindi more as an identity marker than as an effective official language. With the available provisions for the use of English as an "associate official language" for an indefinite period, and with the growth of globalization, one may even expect that the use of English will continue to the detriment to the further growth of Hindi. In due course, if this trend continues, English is sure to restrict the domains of uses for which official Hindi is being equipped with terms and other nuances, or make use of Hindi a superfluous phenomenon, more as a mark of identity.

- In fact, it appears that, by a quirk of circumstances, Hindi may become the most popular language as a carrier of pan-Indian modern civilization, but may not fulfill the original intent of making Hindi the Official Language of India.

STATUS OF HINDI IN INDIA - 2000

|

Sl.No |

State |

Hindi % 1991 |

Official Status |

Educational Status |

||||

|

OL |

RL |

ML |

FL |

SL |

TL |

|||

|

1 |

AN Islands |

17.62 |

Yes & E |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

2 |

Andhra Pradesh |

02.77 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

|

3 |

Arunachal Pradesh |

07.31 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

|

4 |

Assam |

04.62 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

5 |

Bihar |

80.86 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

6 |

Chandigrah |

61.07 |

- |

Yes

|

- |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

|

7 |

Dadra, NH |

05.05 |

Yes anl |

- |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

|

8 |

D & Diu |

3.59 |

yesGE |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

9 |

Delhi |

81.64 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

|

10 |

Goa |

03.17 |

- |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

|

11 |

Gujarat |

02.94 |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

|

12 |

Haryana |

91.00 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

13 |

Himachal Pradesh |

88.87 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

14 |

Jammu & Kashmir |

17.32 |

- |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

15 |

Karnataka |

01.97 |

- |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

16 |

Kerala |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

17 |

L Dweep |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

18 |

Madhya Pradesh |

85.55 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

19 |

Maharastra |

07.81 |

Yes2 |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

|

20 |

Manipur |

01.31 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

|

21 |

Meghalaya |

02.19 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

22 |

Mizoram |

01.28 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

23 |

Nagaland |

03.36 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

24 |

Orissa |

02.40 |

- |

- |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

25 |

Pondicherry |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

26 |

Punjab |

07.29 |

Yes2 |

- |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

|

27 |

Rajasthan |

89.56 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

28 |

Sikkim |

04.87 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

29 |

Tamil Nadu |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

30 |

Tripura |

01.66 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

31 |

Uttar Pradesh |

90.11 |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

32 |

West Bengal |

06.58 |

- |

- |

Yes |

- |

- |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

13 |

9 |

18 |

15 |

12 |

17 |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brass, Paul R.1974. Language. Religion and Politics in North India. London: Cambridge UP.

Census of India 1991. Language Tables.

Chaklader, Snehamony. 1981. Linguistic Minority as a Cohesive Force in Indian Federal Process. Delhi: Associated Publications Home.

Chatterjee, Suniti Kumar. 1943. Languages and the Linguistics problems, Bombay: Oxford UP.

Chatterji, Suniti Kumar. 1973 India: A Polygot Nation and Its Linguistic Problems vis-a- vis National Integration. Bombay: Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Research Centre, Hindustani Prachar Sabha.

Constituent Assembly Debates September 12-14, 1949.

Comprehensive Glossary of Administrative Terms:Hindi-English. 1992. Commission for Scientific and Technical Terminology. Government of India, Department of Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development. Delhi.

Crawford James. 2000. http://ourworld.compuserve.com.

Das Gupta, Jyotirindra. 1970. Language Conflict and National Development Group Politics and National Language Policy in India. Bombay: Oxford UP.

Desai, M.P. 1957. The Language Pattern under the Constitution. Ahmedabad: Navajivan.

Fishman, J. A., Ferguson, C.A. and Das Gupta, J. (ed.) 1968.Language Problems of Developing Nations. New York: Wiley.

Gandhi, M.K. 1956. Thoughts on National Language. Ahmedabad: Navajivan.

Gandhi, M.K. 1958. Hindi and English in the South. Ahmedabad: Navajivan.

General Secretary. Linguistic Minorities Protection Committee vs State of Karnataka. Indian Law Reports-Karnataka Vol.39 Part 11 1st June 1989 pp. 1595-1615.

Glyn, Lewis E. 1972. Multilingualism in the Soviet Union : Aspects of Language Policy and its Implementation. The Hague: Mouton.

Grierson, G A: 1901, Linguistic Survey of India, Vol. VI.

India, Government of. Souvenir of All India Official Language Conference 1978, by H.B. Kamsal and R.K. Sharma. New Delhi.Kautilya. 1960. Kauilya's Artha Shastra, translated by R. Shamasastry, Mysore: Mysore Printing and Publishing House.

Kodanda Rao, P.1969. Language Issue in the Indian Constituent Assembly, 1946-1950. Bombay: International Book House.

Kumaramangalam, S. Mohan. 1965 India's Language Crisis : An Introductory Study. New Delhi: New Century Book House.

Le Page, R. R. 1964. The National Language Question: Linguistic Problems of Newly Independent States. London: Oxford UP.

Mallikarjun, B. Language Use in Administration and National Integration. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages. 1986.

Mallikarjun, B. Evolution of Language Policy for Education in Karnataka. 2001. In Papers in Applied Linguistics -I edited by K.S.Rajyashree and Udaya Narayana Singh. Mysore : CIIL. pp. 122-145.

Mallikarjun, B. 2003. Globalization and Indian Languages. In Linguistic Cultural Identity and International Communication. Ed. by Johann Vielberth and Guido Drexel. Saarbrucken: AQ-Verlag. pp.23-46.

Mallikarjun B. Indian Multilingualism, Language Policy and the Digital divide. 2004. Proceedings of the SCALLA 2004 Working Conference: Crossing the Digital Divide - Shaping Technologies to Meet Human Needs.

Marshall, David F. 1985. The question of an official Language. U. of Dakota.

Mazumdar, Satyendra Narayan. 1970. Marxism and the Language problem in India. New Delhi: People's Publishing House.

National Policy on Education. 1968. Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Government of India.

Nehru, Jawaharlal. 1937. The Question of Language. Allahabad: Congress Political and Economic Studies.

Pattanayak, Debi Prasanna. 1971. Language Policy and Programmes. New Delhi: Ministry of Education and Youth Services.

Prakash, Karat. 1973. Language and Nationality Politics in India. Bomaby: Orient Longman.

Rajagopalachari, C. 1962. The Question of English. Madras: Bharatan Publications.

Rao, V. K. R. V. 1978. Many Languages and One Nation: The Problem of Integration. Bombay: Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Research Centre and Library.

Report of the University Education Commission (1949) or Report of the Radhakrishnan Commission

Reports of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities. 2000. Vol.38. Government of India.

Report of the Committee on Emotional Integration, 1962. Government of India.

Report of the Linguistic Provinces Committee, 1948. Government of India.

Report of the Official Language Commission, 1965. Government of India.

Report of the Committee of Parliament on Official Language, 1958. Government of India.

Report of the Official Language Conference, 1978. Government of India.

Sixth All India Educational Survey, 1999. Delhi. NCERT.

Shukla, R. S. 1947. Lingua Franca for Hindustan and the Hindustani Movement. Lucknow: Oudh Publishing House.

The Educational System, Oxford Pamphlets on Indian Affairs, 1943.

The Constitution of India. 2004. On-line edition. Government of India.

The Official Languages Act, 1963. 1980. Act No.19 of 1963. Resolution and Rules, Government of India.

Thirumalai, M. S. Freedom Struggle and Language Policy in India. (Unpublished monograph)

Thiruvalluvar. The Kural of the Maxims of Tiruvalluvar, (Tr.) by V.V.S. Aiyar. Tiruchirapalli: Dr. V.V.S. Krishna Murthy. 1961.

This paper was presented in the CONGRESS OF WORLD'S MAJOR LANGUAGES, organized by Dewan Bahasa Dan Pustaka, (Department of Official Language), Government of Malaysia, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from October 5 to 8, 2004.

CLICK HERE FOR PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF LANGUAGE PLANNING IN MALAYSIA - Looking Ahead to the Future | THE BIG THREE: CHINESE, ENGLISH, AND SPANISH | CONCEPT OF TIME | FIFTY YEARS OF LANGUAGE PLANNING FOR MODERN HINDI - The Official Language of India | DEWAN BAHASA DAN PUSTAKA, Institute of Language and Literature Malaysia - A Brief Overview | TOWARDS SOME "STANDARD" TELUGU | UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF LINGUISTIC RIGHTS | TRADITION, MODERNITY, AND IMPACT OF GLOBALIZATION - WHITHER WILL TAMIL GO? | HOME PAGE | CONTACT EDITOR

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D.

Central Institute of Indian Languages

Mysore 570006, India

mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net

Send your articles

as an attachment

to your e-mail to

thirumalai@bethfel.org.